Harvard Library has removed human skin from the binding of an 1880s edition of Arsène Houssaye’s book Des destinées de l’âme (The Destinies of the Soul, 1879), held at Houghton Library. The volume’s first owner, French physician and bibliophile Dr. Ludovic Bouland (1839–1933), bound the book with skin he took without consent from the back of an unclaimed deceased woman in a French psychiatric hospital where he worked.

Harvard Library has removed human skin from the binding of an 1880s edition of Arsène Houssaye’s book Des destinées de l’âme (The Destinies of the Soul, 1879), held at Houghton Library. The volume’s first owner, French physician and bibliophile Dr. Ludovic Bouland (1839–1933), bound the book with skin he took without consent from the back of an unclaimed deceased woman in a French psychiatric hospital where he worked.

Bouland was from Metz in the northeastern French province of Lorraine and Arsène Houssaye was a personal friend of his. He gave the doctor a copy of his new book and Bouland had it rebound. A handwritten letter signed by Bouland found inside the book described the binding:

“This book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance. By looking carefully you easily distinguish the pores of the skin. A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering: I had kept this piece of human skin taken from the back of a woman. It is interesting to see the different aspects that change this skin according to the method of preparation to which it is subjected. Compare for example with the small volume I have in my library, Sever. Pinaeus de Virginitatis notis which is also bound in human skin but tanned with sumac.”

As noted in his note, Bouland bound at least one other book in human skin, a copy of De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis (On the integrity and corruption of known virgins, 1663), a collection of gynecological essays by various authors.

That book found a permanent home when it was added to the medical collections of London’s Wellcome Library. The Wellcome also owns a notebook labelled as bound in the skin of “the Negro whose Execution caused the War of Independence,” presumably Crispus Attucks, but the library doubts that it is actually human skin.

That book found a permanent home when it was added to the medical collections of London’s Wellcome Library. The Wellcome also owns a notebook labelled as bound in the skin of “the Negro whose Execution caused the War of Independence,” presumably Crispus Attucks, but the library doubts that it is actually human skin.

The Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia owns five confirmed anthropodermic books on display in the associated Mutter Museum. The John Hay Library at Brown University owns four confirmed anthropodermic books.

The Destinies of the Soul has been in the collections of Harvard Library since 1934, initially placed on deposit by John B. Stetson, Jr. (1884–1952), an American diplomat, businessman, and Harvard alumnus, and later through donation by his widow Ruby F. Stetson to Houghton Library in 1954.

The removal of the human skin from Des destinées de l’âme follows a review by Houghton Library of the book’s stewardship, prompted by the recommendations of the Report of the Harvard University Steering Committee on Human Remains in University Museum Collections issued in fall 2022.

Harvard Library and the Harvard Museum Collections Returns Committee concluded that the human remains used in the book’s binding no longer belong in the Harvard Library collections, due to the ethically fraught nature of the book’s origins and subsequent history.

The Library is now in the process of conducting additional provenance and biographical research into the book, Bouland, and the anonymous female patient, as well as consulting with authorities at the University and in France to determine a final respectful disposition of these human remains.

In the course of its review, the library noted several ways in which its stewardship practices failed to meet the level of ethical standards to which it subscribes. Until relatively recently, the library has made the book available to anyone who asked for it, regardless of their reason for wishing to consult it.

Library lore suggests that decades ago, students employed to page collections in Houghton’s stacks were hazed by being asked to retrieve the book without being told it included human remains.

In 2014, following the scientific analysis that confirmed the book to be bound in human skin, the library published posts on the Houghton blog that utilized a sensationalistic, morbid, and humorous tone that fueled similar international media coverage.

In a press announcement sent by Harvard University said “Harvard Library acknowledges past failures in its stewardship of the book that further objectified and compromised the dignity of the human being whose remains were used for its binding. We apologize to those adversely affected by these actions.”

“The core problem with the volume’s creation was a doctor who didn’t see a whole person in front of him and carried out an odious act of removing a piece of skin from a deceased patient, almost certainly without consent, and used it in a book binding that has been handled by many for more than a century,” according to Tom Hyry, Associate University Librarian for Archives and Special Collections and Florence Fearrington Librarian of Houghton Library. “We believe it’s time the remains be put to rest.”

The book without the binding has been fully digitized and is publicly available. The human skin used to bind the book is not available, in person or digitally, to any researcher. The human remains removed from Des destinées de l’âme are currently in secure storage at Harvard Library according to Hyry.

Two other books at Harvard, one in the Law School Library, one in the Countway Library’s Center for the History of Medicine, had inscriptions identifying them as examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy (the official term for book binding using human skin).

The Law School book is Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae, a treatise on Spanish law by Juan Gutiérrez published in Madrid in 1605. An inscription on the last page of the book claimed:

“The bynding of this booke is all that remains of my dear friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632. King Mbesa did give me the book, it being one of poore Jonas chiefe possessions, together with ample of his skin to bynd it. Requiescat in pace.”

That book’s binding was DNA tested in 1992 but the results were inconclusive, most likely because of the tanning process. A year after that, a new analytical technique called peptide mass fingerprinting was developed.

Peptide mass fingerprinting breaks proteins up into component peptides whose masses can be measured by mass spectrometer and the results compared to a database of known proteins. In the Spring of 2014, peptide mass fingerprinting conclusively proved the binding to be sheepskin, not the product of Jonas Wright’s flaying.

The Countway Library book is a 1597 French translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses which has a faint inscription in pencil on the inside cover stating simply “Bound in human skin,” but experts doubted its accuracy because the binding doesn’t look like other confirmed human leather bindings. Peptide mass fingerprinting proved that it too had a sheepskin binding.

You can learn more about anthropodermic bibliopegy in this essay by New York Almanack contributor Jaap Harskamp.

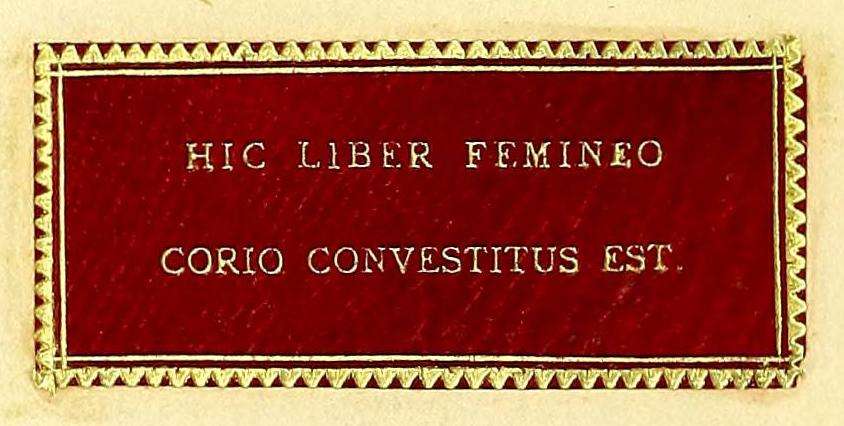

Illustrations, from above: Panel with Latin inscription in the book Hic liber femineo corio convestitus est, reading “This book has been bound with the skin of a woman”; and “Human Hide Industry – Its Extent in Massachusetts – Both Sides of the Question,” 1883 (National Library of Medicine) – a larger version is located here.