On the surface, we all know that turtles are animals with shells. They plod along on land, or swim gracefully in the water. Some live in the oceans, some in the deserts – what wonderful extremes they have come to inhabit. They have been around for over 200 million years – since the late Triassic. Some species can live well over a hundred years. If we dig deeper though, they are even more fascinating.

On the surface, we all know that turtles are animals with shells. They plod along on land, or swim gracefully in the water. Some live in the oceans, some in the deserts – what wonderful extremes they have come to inhabit. They have been around for over 200 million years – since the late Triassic. Some species can live well over a hundred years. If we dig deeper though, they are even more fascinating.

It takes an awfully long time for a turtle to become reproductive (ten or more years). It is currently believed that this is because after birth young turtles put most of their energy into developing their shells.

The turtle’s shell is its means of protection, and until the advent of the motorized vehicle, it served the animals well. Once completely developed, the turtle’s shell is a formidable defense. There aren’t too many natural predators that can kill a turtle. A good shell, therefore, is imperative to survival; offspring can come later.

Next, there’s the method by which a turtle breathes. Like reproduction, a turtle’s breathing is tied to its shell. Anyone who has seen a turtle shell sans turtle has noted that the animal’s ribs are fused to the inner carapace (the carapace is the upper portion of the shell; the plastron covers the belly). You and I manage breathing because our rib cages can expand with our lungs. Not so the turtles.

Instead, they have a special musculature that, as so eloquently put in The Reptiles and Amphibians of New York State, “sloshes the internal organs back and forth to draw air in and out of the lungs.”

One set of respiratory muscles pulls all the internal organs outwards towards the edges of the shell. This allows the lungs, which are located near the top of the shell, to fill with air. The second set of muscles pushes everything back inwards, pressing against the lungs to expel the air. How wonderfully adaptive!

Temperature affects sex. That is, temperature determines the sex of a turtle. When I first learned this, I thought it was just amazing. It seems that the warmer eggs develop into females, while the cooler eggs, which tend to be toward the bottom of the nest, develop into males.

Temperature affects sex. That is, temperature determines the sex of a turtle. When I first learned this, I thought it was just amazing. It seems that the warmer eggs develop into females, while the cooler eggs, which tend to be toward the bottom of the nest, develop into males.

Depending on climate, in some years nests can produce mostly female turtles, while other years the balance tips in favor of males. Will climate change affect this? If most nests yield females, how will our turtles find enough males to reproduce? It’s an interesting question.

Eighteen species of turtles live in New York State, nearly all the native species are threatened and endangered. Here are some details about three species that I find among the most interesting:

Snapping turtles, those truly dinosaurish turtles, are probably the turtle we see most often. Every spring the females leave their watery homes in search of the perfect sandy spot in which to dig holes and lay eggs. Most of these eggs will be eaten by predators, but the survivors hatch by late summer.

Sometimes the newly hatched turtles leave the nest immediately, while others opt to remain in the relative safety of the nest over winter, which explains why baby snappers are found on the move in both the spring and the fall.

When they aren’t out searching for nest sites, these turtles are most often lying low in the muddy substrate of shallow, slow-moving waters, which is why their shells are “mossy” – these turtles are not baskers.

Despite the apparent commonness of the species, recent population studies show that snapping turtles are in decline across New York State, mostly as a result of fatal encounters with motorized vehicles.

Despite the apparent commonness of the species, recent population studies show that snapping turtles are in decline across New York State, mostly as a result of fatal encounters with motorized vehicles.

Wood turtles are close to my heart. Every spring they too search for perfect nest sites along the sandy shoulders of our roads. Their populations are considered sporadic, possibly because they are terrestrial and often on the move.

One of our larger turtles, the wood turtle stands out among its brethren on two accounts: it has brilliant orange markings along its neck, forelegs and tail, and it is considered to be quite intelligent. Sadly, these turtles are frequently exploited in the pet trade, which compounds their losses to fast-moving traffic.

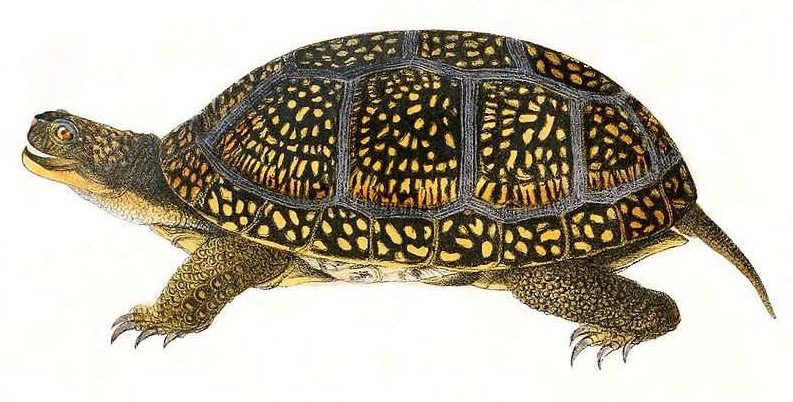

The third is the Blanding’s turtle. In New York it is a threatened species and not frequently seen.

Blanding’s turtles are on the largish end of the land turtle scale, smaller than the snappers, but comparable to wood turtles. What stands out is their highly domed shells and their yellow chins.

If necessary, the Blanding’s turtle (named for William Blanding, a physician and naturalist from Massachusetts who collected the original specimen in 1830) can close the front end of its shell, like a box turtle, for protection. (Box turtles can actually close both the front and back ends of their shells.)

If necessary, the Blanding’s turtle (named for William Blanding, a physician and naturalist from Massachusetts who collected the original specimen in 1830) can close the front end of its shell, like a box turtle, for protection. (Box turtles can actually close both the front and back ends of their shells.)

It breaks my heart that so many species of turtles are in decline. We (as a species) eat them, capture them for the pet trade, toss them aside as by-kill in the fishing industry, and run them over with our cars. Their homes are lost to development and pollution.

I sometimes wonder if this ancient line of animals, who have survived so much, will survive humans.

Wild turtles shouldn’t be pets, and pet turtles, which may not be native species, should not be released into the wild when their novelty wears off. If you see a turtle trying to cross the road, slow down – and give it a chance to make the journey.

Illustrations, from above: Turtles basking at North Pond in Town of Hague (photo by John Warren); a snapping turtle laying eggs in the road sand on the edge of a road in Northern Warren County (John Warren); a wood turtle (photo by Wikipedia user ); and a Blanding’s turtle in