Canals were the first transportation revolution in New York, but they were eclipsed in a few decades by extensive railroad development. Starting in the 1840s, railroads shipped goods faster than canal barges and provided additional inland routes to the Midwest as it emerged as the breadbasket of the expanding nation.

Canals were the first transportation revolution in New York, but they were eclipsed in a few decades by extensive railroad development. Starting in the 1840s, railroads shipped goods faster than canal barges and provided additional inland routes to the Midwest as it emerged as the breadbasket of the expanding nation.

These western routes resulted in an agricultural shift in the Finger Lakes region. Instead of focusing on wheat, a product that could easily be milled and shipped long distances, many Finger Lakes farmers switched to commercially growing fruits and vegetables, meat, and dairy that railroads could deliver to the growing urban populations.

With its relatively temperate climate, Yates County earned the reputation as the “Fruit Basket of New York State” for the many acres of commercial peaches, plum, apricot, and apple orchards along the shores of Seneca, Keuka, and Canandaigua Lakes.

Wayne County, along the shore of Lake Ontario, became the top apple producer in the state. Canneries appeared around the canals to process the many fruits and vegetables grown in the region. Dairies and dairy-related crops became increasingly common in Ontario and Steuben Counties.

New York State agriculture peaked during the mid-19th century. During the 1850, Wayne County produced approximately 50% of the nation’s peppermint oil. Skaneateles was center of the teasel industry in the United States, growing more of the thistles — used to brush woolen fabric at cloth mills — than anywhere else in the country.

Geneva (Ontario County) on the northern shore of Seneca Lake and Rochester (Monroe County) became known for ornamental tree and fruit tree nurseries; by the 1870s, the Rochester area was known as “the flower city” and the horticultural center of the nation.

Chemung County gained a reputation for high-quality butter and leaf tobacco, as well as its celery, which was considered a luxury item and status symbol in Victorian cuisine.

As part of New York State’s agricultural success, Finger Lakes wine gained an international reputation. The wine industry the Finger Lakes region is now known for was started in the 1830s. Hearty, native species of grapes were widespread across the Northeast and gathered by the Haudenosaunee.

In 1829, Reverend William Bostwick planted native Catawba and Isabella grapes at his rectory in Hammondsport for use in sacramental wine production. A few years later in 1836, the first commercial grape grower and wine producer in the Finger Lakes, J.W. Prentiss, sold grapes grown on the shores of Keuka Lake to cities across the eastern United States through canal transportation corridors.

Prentiss’s wine was not especially well received, considering he wasn’t an experienced winemaker, and the majority of rural Americans in the early 19th century drank hard cider created from their own apple orchards.

German immigrants in cities preferred beer brewed at local, small-scale breweries to wine. While Prentiss did not experience broad success, his operation piqued the interest of skilled winemakers from the Ohio Valley who brought commercial success to Finger Lakes’ vineyards a few decades later.

The Finger Lakes wine industry expanded during the 1860s with vineyards appearing around Keuka, Seneca, and Cayuga Lakes — the larger and deeper the lake, the better regulated the shorelines’ temperatures.

Skilled winemakers took control of the production side of the business; more than 3,000 acres of grape vines were planted along the shores of Keuka, Canandaigua, and Seneca Lakes during the 1860s, and barges of grapes became a common sight on the Cayuga-Seneca and Crooked Lake Canals.

Reminded of France’s Champagne region by the soil and climate conditions found near Keuka Lake, Charles Champlin founded Pleasant Valley Winery in Hammondsport and began planting Champagne grapes in America.

Pleasant Valley Winery in Hammondsport became the first bonded winery in the United States in 1860. Under the supervision of two master French winemakers hired by Champlin, Great Western Champagne made by Pleasant Valley Winery was introduced in Europe in 1867 to surprising acclaim.

Demand for Finger Lakes champagne increased after an 1873 win at an international wine competition in Vienna, Austria. Over the next decades, the industry grew exponentially; by 1900, the region included 20,000 acres of vineyards and more than 50 wineries producing more than 7 million bottles of champagne, twice as much sparkling wine than all other states combined.

Early entrepreneurs recognized the economic potential held in the waters of the Finger Lakes – Genesee Valley. In 1864, “the Father of American Fish Culture” Seth Green selected Caledonia’s Spring Creek (Livingston County) as the location of the nation’s first fish hatchery because of the area’s clear water, consistent water temperature and flow rate, and low amount of surface run-off that could muddy the stream, calling Spring Creek “one of the best places we have ever seen for the purpose, and we doubt it can be equaled.”

Green grew the hatchery into a business, shipping eggs and spawn worldwide via Caledonia’s three railroad connections and providing trout stock for the many public lakes and rivers. The State of New York purchased the Caledonia Hatchery from Green in 1875 and named him Supervisor of Fisheries, the government position responsible for stocking the state’s waterways.

During the Civil War, railroads continued to expand in the Finger Lakes region, providing businesses a quicker way to move agricultural products and manufactured goods to market. This shift and the increased connectivity provided by railroads facilitated industrialization within the Finger Lakes region. The region’s major cities of Rochester and Syracuse embraced industrialization and large-scale manufacturing.

Rochester became a seat of technological innovation, with the founding of Bausch & Lomb (founded 1853, eyeglasses and frames), Eastman Kodak (incorporated 1892, photographic cameras and flexible film), and Xerox (founded 1906, photography paper).

Syracuse became a hub of industrial activity with firms producing typewriters, soda ash, farm implements, automobiles, shoes, iron and steel, food products. The city was also the first home of Carrier Engineering Corporation (founded 1915), a company founded by inventor of modern air conditioning Willis Carrier to create heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

Smaller communities throughout the region also embraced manufacturing and used industrialized processes to produce brooms, agricultural tools and machinery, gypsum, cloth, wood items, caskets, clocks, buttons, and globes into the 20th century. Seneca Falls became a center for mechanical pump manufacturing and later fire engines.

In 1873, Cortland’s Chester Wickwire modified a carpet loom to cheaply and efficiently weave wire; by the 1880s, the Wickwire Brothers Factory manufactured numerous products that benefitted rural Americans: window screens, horse muzzles, seed spreaders, strainers, chicken wire, and barbed wire.

Corning became the home of some of America’s best cut glass starting in 1880s and one of the first industrial research labs in 1908.

Hammondsport native Glenn H. Curtiss first made a name for himself manufacturing motorcycles but became one of the founders of American aviation when he applied his lightweight motor to aircraft. Curtiss was a founding member of the Aerial Experiment Association and formed the Curtiss Aeroplane Company in 1910.

The company — which was later known as the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company — grew to become the world’s largest aviation manufacturer during World War I, employing 3,000 people at its Hammondsport location and an additional 18,000 people at the Buffalo, New York, facility that became the company’s headquarters in 1918.

Central New York was also connected to design elements that have come to define the early 20th-century American architectural arts. The Stickley Brothers started a furniture company in Fayetteville (Onondaga County) in 1900 that became a leader in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Their Craftsman-style furniture was built to be “honest,” which was a departure from the gaudy style of the late 19th century and low-quality pieces that were being created in early industrial furniture factories, and the company’s Mission Oak designs showcase high-quality wood, natural finishes, and simplicity.

Irene Sargent, a professor at Syracuse’s College of Fine Arts and Auburn native, helped further popularize the Arts and Crafts Movement by launching The Craftsman, a monthly style journal that showcased the style. Sargent was the magazine’s managing editor and layout designer during its 15-year run (1901-1916).

The increase in capital and philanthropy in the Finger Lakes’ manufacturing sector following the Civil War allowed higher education to flourish. Additional institutions of higher learning were established throughout the region: Wells College (Aurora), founded as a women’s college in 1868; Syracuse University, established in 1870 as a coeducational college; Keuka College (Keuka Park), founded in 1890 as an institution that any could attend regardless of economic background; Ithaca College, founded as a music conservancy in 1892; the University of Rochester began admitting female students in 1900; as well as the William Smith School for Women (Geneva), and the sister school for Geneva College in 1908.

Some Finger Lake natives embodied the region’s social reform and went on to share their progressive agendas on a national stage near the end of the 19th century. Robert Green Ingersoll, a native of Dresden who gained fame as “The Great Agnostic,” emerged as one of the most popular post-Civil War orators and free thinkers in the country.

Belva Lockwood earned a degree from Genesee College in Lima (Livingston County) before teaching at a variety of girl’s academies in upstate New York. It was during her three years of teaching at a female seminary in Owego that she incorporated Susan B. Anthony’s approach to education and expanded curriculum to include business, public speaking, botany, and other subjects not traditionally taught to women and ultimately decided to pursue law.

Lockwood moved to Washington, DC, and she eventually became the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court and the first women to officially run for president when she was included on the ballot during the 1880 and 1884 national elections.

Amelia Stone Quinton, who was raised in Jamesville (Onondaga County), went on to found the Women’s National Indian Association in 1879; the national organization supported assimilation through Christian missionary work, lobbied for Congress to uphold Indian treaties, and spoke out against white encroachment and settlement in the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

Mary Clark Thompson, the daughter of New York Governor Myron Clark, grew up in Canandaigua and attended school at the Ontario Female Seminary. After marrying banker Frederick Ferris Thompson—one of the founders of the First National Bank of New York and the Chase Bank of New York — and moving to New York City, Mary convinced her husband to spend the summers in Canandaigua.

Clark Thompson became a generous benefactor for both communities she lived in by donating to civic, religious, and educational institutions. She was one of the founders of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and a donor to the Bronx Zoo, Women’s Hospital, and several colleges.

She shaped civic life in early 20th-century Canandaigua by establishing the F. F. Thompson Hospital and Chase Retirement Home and donating to construct the city’s post office, support the Ontario County historical society, and Wood Library.

Harriet May Mills, born in Syracuse a few years after the city hosted the 1852 National Women’s Conference, represented the next generation in the ongoing fight for women’s suffrage. Mills worked tirelessly organizing women’s rights conferences and suffrage events across the country, helping build support in New York, California, Michigan, and Ohio and serving as a leader in national suffrage and Democratic political organizations during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Soon after the Civil War, Waterloo (Seneca County) was the site of the first formal, village-wide, annual observance of a day dedicated to those who had died during war. Local druggist Henry C. Welles and Seneca County Clerk and Civil War brigadier general John B. Murray led efforts to decorate soldiers’ graves and hold remembrance ceremonies for the dead in May 1866, 1867, and 1868.

In that year, the holiday — then called Decoration Day and now known as Memorial Day — was nationally proclaimed by the Grand Army of the Republic and celebrated at Arlington National Cemetery.

Clara Barton visited Dansville as a tour stop during the late 1860s to give lectures on her experiences as a Civil War nurse. She later returned to the Livingston County community to stay at the “Our Home on the Hillside” sanitarium and health spa before purchasing a home in the community.

During this time, Barton worked tirelessly to organize a national health organization modeled after the International Committee of the Red Cross, finally establishing the American Association of the Red Cross in May 1881. The first local chapter of the new organization was chartered in Dansville in August of that year. Barton was an ardent suffragist and continued to support the cause after she move from Dansville to Washington, DC, in 1896.

Although industry’s influence grew in post-Civil War decades, the majority of the Finger Lakes region continued to be rural and rely on agricultural products for income. Chartered to support the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act, Cornell University opened in the fall of 1868 and welcomed the largest entering class at any American university up to that time.

Although Cornell was chartered as a private university, it was required to offered courses focusing on agriculture and industrial arts as New York’s land grant college focused on bringing the benefits of higher education to a wider population through research and outreach. The university formally opened its Department of Agriculture in 1874 and later merged the agriculture, chemistry, botany, entomology, and veterinary medicine to create the College of Agriculture in 1888.109

Knowing that eastern states would need to improve farming practices to remain competitive with western states in the decades that followed the Civil War, the State of New York established the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in 1880.

Located in Geneva (Ontario County), the research facility that used scientific methodology to research and examine agricultural production and practices. When the station opened in 1882, scientists focused on the study of vegetable and grain varieties, horticultural practices, and the dairy industry; over the next decade, the program expanded to include research on fruit varieties, swine, and beef cattle.

In the 1890s, the typical Finger Lakes farm was modestly sized and diversified. Most families had cows, pigs, chickens and substantial gardens that took advantage of the nutrient-rich soil and idealized growing conditions. Like early during the canal era, agricultural products that could be locally processed were major sources of outside income for local farmers.

Popular products from the Finger Lakes at the end of the 19th century were hops and barley that supported local breweries, sheep that provided wool and meat, black raspberries that could be made into dye for Jello — invented in Leroy, New York — apples for fresh sale, and grapes.

This essay is drawn from the National Park Service’s Finger Lakes National Heritage Area Feasibility Study. You can read about the study and the Finger Lakes National Heritage Area here.

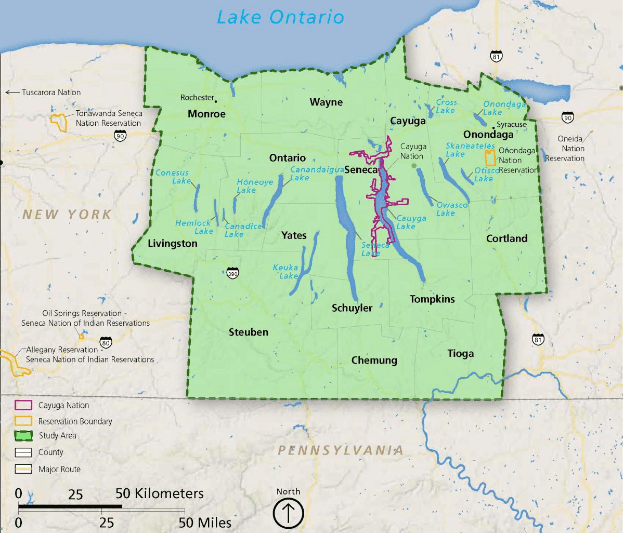

Illustration: National Park Service Map of Finger Lakes National Heritage Area Study Area.