Getty Images

Getty ImagesAhead of their record-making fifth Glastonbury appearance – why the British rock band have overcome the naysayers to become the era’s most triumphant artists.

It is strange to recall a time when Coldplay were not ubiquitous. I first met frontman Chris Martin, guitarist Jonny Buckland, bass-player Guy Berryman and drummer Will Champion at what they later described as the worst show they had ever played. It was the Paredes de Coura festival in Portugal in August 2000. By their own admission, they failed to win over an apathetic crowd and were utterly outshone by headliners The Flaming Lips. At home, their debut album Parachutes was a Mercury-nominated smash destined to sell five million copies. In Portugal, nada. As the set limped on, Martin became cripplingly apologetic. “Has anyone ever heard of us here?” he asked plaintively before playing Yellow. “This is our hit single in England.”

His insecurity was compounded by a swelling backlash at home. They were widely characterised as a more wide-eyed Travis or a U-rated Radiohead for people who didn’t like the weird stuff. To some, they epitomised British rock’s post-Britpop malaise: pleasant, tuneful young men who still looked like the students they had so recently been and were not remotely rock’n’roll. It got heated.

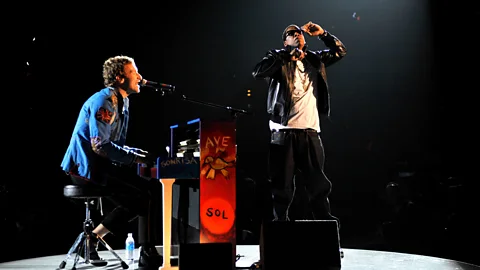

“People who don’t like you talk about you like you’re the Third Reich,” Martin protested. Even as they proceeded to become the biggest band in Britain, and then one of the biggest in the world, the brickbats kept coming. In 2005, The New York Times called them “the most insufferable band of the decade”. In a brutal 2008 screed called Why I Hate Coldplay, the Independent’s Andy Gill compared their music to “wilted spinach”. So convinced were their detractors of Coldplay’s profound uncoolness that the endorsement of people as credible as Jay-Z and Brian Eno did not compute.

Even Martin was surprised. He and Jay-Z ended up becoming friends who featured on each other’s records, but when they first met he struggled to understand what the sleek rap kingpin who grew up in a crime-ravaged Brooklyn housing project saw in his middle-class British indie-rock band. “When Jay first said ‘I like your band’, I was like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?'” he told me in 2011. “‘No, you don’t.’ Then I realised he doesn’t bring any baggage to it. ‘I like your songs’ – it was as simple as that.”

These days, as Coldplay prepare to become the first artists to headline Glastonbury five times, there is no sport in wielding the hatchet. The most successful group of the 21st Century by some margin, they have sold more than 100 million albums, won more than 300 awards and racked up nine billion-stream songs. So far on their ongoing Music of the Spheres tour, already the third highest-grossing of all time, they have played to more than 7.6 million people from Costa Rica to Singapore, including six nights at Wembley Stadium and an extraordinary 10 at Argentina’s River Plate Stadium.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNo other rock band has such global reach, if indeed that is what they are. “Coldplay are not a rock band,” Bono insisted in Radio 1’s gushing documentary The Genius of Coldplay. “They should not be judged by rock rules.” He meant that their fuel is not rage or confrontation, but sincere inclusivity. This quality has made them the defining band of this post-genre, post-cool, post-gatekeeper era, dominating the centre of pop’s Venn diagram. Their collaborators and admirers include Beyoncé, Bruce Springsteen, U2, Michael Stipe, Rihanna, Frank Ocean, Kanye West, Stormzy, Lizzo, Femi Kuti, Nick Cave, Dua Lipa and Janelle Monáe. They like the songs. It’s as simple as that.

Stream Glastonbury 2024

For the first time, the BBC is livestreaming Glastonbury performances to a global audience, with Coldplay’s 2024 Pyramid Stage set available to view on bbc.com, offering fans around the world a front-row seat to headline acts like never before.

When I spoke to Martin again towards the end of 2000, he was newly cagey about discussing his background because it had been held against him. Born in Devon in 1977 to a chartered accountant and a music teacher, he attended Sherborne boarding school, where he played in a Blues Brothers-style outfit called The Rockin’ Honkies with his best friend Phil Harvey, Coldplay’s future manager and unofficial fifth member. “I was playing piano and dancing like a tosser,” he said in 2011. “So not much has changed there.” The members of Coldplay met at UCL in 1996 and ended up taking their nebulous name from another student band that had discarded it. In 1999, with one EP to their name, they played the New Bands Tent at Glastonbury thanks to the fandom of 19-year-old Emily Eavis. And then came Yellow. Around that time, Martin joked about one day being as big as Bon Jovi: a plainly ridiculous scenario.

Coldplay’s first decade was shaped by action and reaction. Criticism of Parachutes’ gentle naivety drove them to make 2002’s burlier A Rush of Blood to the Head, their 17 million-selling global breakthrough. X&Y, from 2005, was recorded by a band under great strain in the glare of Martin’s relationship with Gwyneth Paltrow and sounded like a cry for help from inside a space station. For 2008’s Viva La Vida, Or Death and All His Friends, they reestablished their chemistry and learned to take more risks under Brian Eno’s tutelage. Prone to misty generalities, Martin wrote perhaps his sharpest lyric for the title track, the lament of a deposed dictator. It was deftly covered by the Pet Shop Boys because it is effectively a Pet Shop Boys song, at least until the colossal woah-woah climax that is one of Coldplay’s superweapons. Even that highlight was overshadowed by a plagiarism lawsuit (Coldplay won), which made Martin even more determined to prove his songwriting chops.

Since then, Coldplay have managed to maintain their popularity without being imprisoned by it. In one lane are the cosmically inclined commercial giants, bringing in Scandinavian hitmakers Stargate and Max Martin: 2011’s Mylo Xyloto, 2015’s A Head Full of Dreams and 2021’s Music of the Spheres. In the other are the interstitial albums they choose not to tour: 2014’s Ghost Stories, a doleful epitaph for Martin’s marriage, and 2019’s rangy, globetrotting, surprisingly political Everyday Life. But even their pop albums take intriguing detours. Music of the Spheres features both My Universe, a shameless megapop crossover with K-Pop stars BTS, and the exquisite 10-minute instrumental Coloratura. Beyond the hits, they are far more interesting than they are given credit for.

In the Radio 1 series, Harvey says that Coldplay are three introverts fronted by one extrovert. Energetic, emotionally transparent and a great cheerleader for life, Martin may be the chief songwriter and publicity magnet but without his bandmates, as friends and musicians, he would be lost. The band learned from U2, REM and Radiohead to democratise decision-making and songwriting credits. Martin, who writes melodies all the time, has said that only one in 10 song ideas gets past the others, with Champion the hardest to impress. Harvey describes the robustly level-headed drummer as the banks of the river, the river being Martin. In 2011, the singer asked me whether I thought they should agree to appear on The X-Factor, which felt to some members like a bridge too far. He wouldn’t reveal how the band was divided but it wasn’t hard to guess.

Martin’s tastes are sincerely universalist. When I asked him in 2011 which songs he wished he had written, he named not just rock anthems like Bittersweet Symphony and Where the Streets Have No Name but standards such as Somewhere Over the Rainbow and What a Wonderful World. He has no qualms about loving the obvious because those are the songs that speak to the most people. Coldplay’s 2015 song Kaleidoscope sampled Barack Obama singing Amazing Grace, a hymn whose potent alloy of anxiety and wonder, pain and healing, gels with the instincts of the band that wrote Fix You and Everything’s Not Lost. Like U2 without the vestigial attachment to punk, Coldplay have a wide-open, salvational quality. The influence of his mother, a devoutly Christian music therapist, is not hard to detect. He is drawn to songs that “sound like they were waiting to be discovered” rather than written.

Another of Martin’s un-rock’n’roll qualities is his duty of care. He used to swing between world-beating self-confidence and punishing doubt, regularly claiming that Coldplay’s latest album would be their last, but at 47 he seems much steadier, with a greater capacity to look outwards. Martin combines voracious curiosity with an unusual lack of cynicism. Like Elton John, he likes to keep up with pop, get under the bonnet of hit songs, and lend a hand to other artists. “There’s a great distance between what Chris does and what I do,” his unlikely friend Nick Cave told Mojo magazine in 2022. “And we acknowledge that. But there’s other things that have always drawn me to Chris and mostly it’s his extraordinary generosity of spirit.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMartin’s most underrated characteristic, absent in the songs, is the sense of humour that Cave describes as “kind of hair-raising”. He has happily parodied himself as a passive-aggressive megalomaniac in Extras and Modern Family, not to mention interviews. I once asked him a generic question about which song he would like played at his funeral. “I don’t really want a funeral,” he deadpanned. “All I want when I die is a simple tribute concert at Wembley Stadium. And maybe a covers album. That’s all I ask.” Coldplay-haters love to tell the story of David Bowie rejecting one of Martin’s songs (“Not your best”) but we only know about it because Martin himself shared it as a self-deprecating anecdote. It is hard to mock someone who is so ready to mock himself.

Martin sees the music world not as a competition but a community, where people should look out for each other. Coldplay have enacted this philosophy most strikingly at Glastonbury. In 2005, when they replaced Kylie Minogue as headline act after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, they covered Can’t Get You Out of My Head in her honour. When she finally made it to the festival in 2019, Martin joined her for that same song, to complete the circle. When Stormzy convinced himself that he had blown his headlining slot that year, it was Martin, a “calming spirit”, who made him feel better. In 2016, Coldplay covered a song by Viola Beach, a young band who had died in a bus crash while on tour on Sweden, “to let them headline Glastonbury for a song”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesReportedly, Martin was embarrassed to be asked to headline a fifth time but Coldplay are the perfect Glastonbury band, with their expansive dedication to communal joy and sincere conviction that the audience is more important than the band. At their first Pyramid Stage appearance, replacing The Strokes in 2002, they had to play six songs from an album that wasn’t out yet and Martin felt moved to say, “I don’t know if any of you have heard of us but we’re called Coldplay.” But as soon as he improvised a charming lyric about Glastonbury in opener Politik, it was clear that he had a direct line to the festival’s heart. In 2016, they handed out radio-operated LED wristbands that made every fan a component of the light show – a hi-tech literalisation of their inclusive philosophy which has since been copied by the likes of Taylor Swift. They have also pioneered efforts to make touring more environmentally sustainable.

The world has changed a lot since 2000, when Coldplay were scorned for being too nice, too emotionally direct, lacking in edge. Today, their profound decency and humanity seems far more valuable. Whether it’s their concern for their fans, their pragmatic environmentalism, their support for younger artists or the songs themselves, always moving towards hope and light, they have become a force for good. There may still be those who find their world-enveloping success baffling or enraging but Coldplay no longer have any need to apologise.

Coldplay headline Glastonbury Festival on Saturday 29 June.