Although not authorized to do so by a strict constructionist reading of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause, Congress enacted the first Fugitive Slave Act in 1793. Northern states blocked effective enforcement of the federal law, leading to a southern outcry for more stringent legislation.

Although not authorized to do so by a strict constructionist reading of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause, Congress enacted the first Fugitive Slave Act in 1793. Northern states blocked effective enforcement of the federal law, leading to a southern outcry for more stringent legislation.

The sectional crisis precipitated by the California Statehood Act in 1850 provided the opportunity for passage of a harsher Fugitive Slave Act, which became part of the Compromise of 1850.

As northern civil disobedience obstructed the effectiveness of the Fugitive Slave Act, southerners became convinced that the constitutional covenant holding the Union together was broken, despite the fact that the federal government had effectively become an agent of the slave-holding interest in addressing the South’s concerns.

Fugitive Slave Act in 1793

The law signed by George Washington in 1793 continued for fifty-seven years to be the only federal legislation concerning fugitive slaves. During all that time, attempts to revise or supplement the statute were surprisingly few, considering the widespread dissatisfaction with the way it worked in practice.

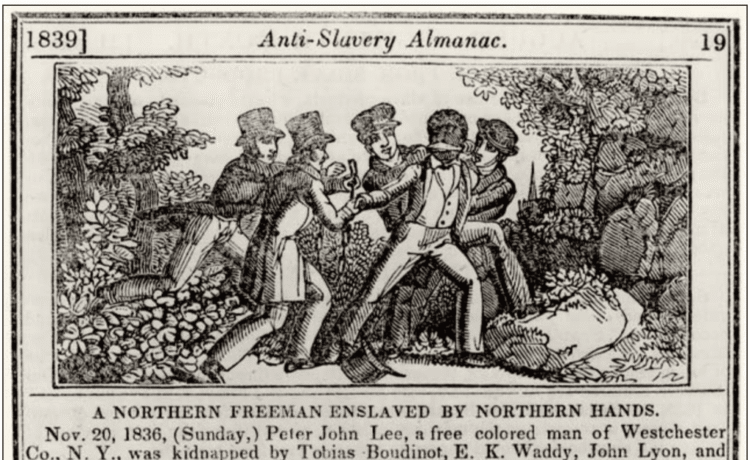

Most notably, Congress remained completely unresponsive to complaints that the law placed free blacks at risk of enslavement and served as cover for a good deal of outright kidnapping.

No bill aimed at ameliorating the racial injustice of the measure was ever introduced or reported in either house, whereas southerners seeking tougher enforcement came close to success on two occasions…

Except as an occasional sounding board for discontent with the act of 1793, Congress played no part in the handling of the fugitive slave problem during the first half of the nineteenth century.

The executive department was more active, but mainly in peripheral ways.

Federal officials enforced the law in the territories and in the District of Columbia; army troops on the frontier were sometimes used to help owners recover runaway slaves; certain treaties with Indian tribes stipulated the return of fugitives; and the State Department made persistent efforts to secure international agreements for the recovery of fugitives from Spanish Florida, Mexico, and Canada.

State Intervention to Protect Fugitive Slaves

Among the three branches of the national government, only the judiciary was functionally involved in the interstate rendition process before 1850, and even its role might be regarded as secondary if it were not for one Supreme Court decision of crucial importance.

Interstate recovery of fugitive slaves was essentially a private enterprise conducted under the authority of federal law within an often uncongenial jurisdiction.

Interstate recovery of fugitive slaves was essentially a private enterprise conducted under the authority of federal law within an often uncongenial jurisdiction.

Certain northern legislatures figure prominently in this, the most melodramatic chapter in the history of American slavery, but the story is primarily an episodic one of pursuers and pursued, of confrontations that occasionally turned violent, and of court cases by the hundreds.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Pennsylvania and New York were the major centers of controversy, both states being then engaged in the gradual emancipation of their own slave populations.

Although a few citizens of those states undoubtedly lent assistance now and then to runaway slaves, there was no extensive desire to interfere with the operation of the law or to encourage an influx of fugitives from the Chesapeake region.

At the same time, two persistent problems drove state governments toward intervention.

One was the question of how to handle an alleged fugitive’s claim that he or she was in fact free. The other was the evidence that free blacks in considerable numbers were being seized and sold into slavery.

Southerners in Congress, by thwarting all efforts to secure federal anti-kidnapping legislation, put added pressure on the free states to provide some kind of protection for their black residents.

Pennsylvania had led the way in 1788 with an amendment to its abolition statute that included a relatively mild penalty for the kidnapping of a black person with the intention of selling him into slavery.

In 1808, the New York legislature became the first to pass a law specifically labeled “An Act to prevent the kidnapping of free people of color.”

It prescribed very severe penalties that were somewhat moderated in later legislation but continued to include the possibility of as much as fourteen years’ imprisonment.

An Ohio anti-kidnapping law enacted in 1819 is of special interest because it forbade the removal of any alleged fugitive from the state without conformance to the procedure set forth in the federal law of 1793.

In effect, this provision abrogated the slaveholder’s right of direct recaption [the right to reclaim one’s wrongfully withheld property] under common law, a right widely believed to have been recognized in the Constitution.

In March 1820, shortly after a fierce and protracted controversy in Congress had ended with passage of the Missouri Compromise, the Pennsylvania General Assembly rather belatedly provided the state with an anti-kidnapping law of some force.

In addition to its severe punitive provisions, the statute forbade justices of the peace and aldermen to play any part in administration of the federal fugitive slave law, and it required other state judicial officers to make and file records of all cases in which they issued certificates of removal by virtue of that law.

Clearly, these restrictions, whatever effect they might have on the kidnapping of free blacks, were bound to make the legitimate recovery of fugitives more difficult.

Clearly, these restrictions, whatever effect they might have on the kidnapping of free blacks, were bound to make the legitimate recovery of fugitives more difficult.

Meanwhile, complaints from the state of Maryland about the escape of slaves across the Mason-Dixon line were becoming more vehement. Pennsylvania responded in 1826 with a law seemingly designed to strike a balance between the rights of slaveholders and the protection of free blacks.

While retaining the anti-kidnapping features of the earlier statute, it authorized the participation of judges, sheriffs, and local magistrates in the recovery process, but made that process more complex and difficult than what was required by federal law.

In addition, it repealed the section of the abolition act of 1780 that had recognized a right of do-it-yourself recaption under common law.

As in Ohio, strictly private capture and removal of a fugitive slave now became the legal equivalent of kidnapping.

Two years later, as part of a general revision of its statutes, New York likewise prohibited private recaption and established a recovery procedure that involved state officials in the apprehension of runaways, as well as in the judicial disposal of their cases.

The New York codifiers went further than Pennsylvania in one respect by permitting an arrested fugitive to sue out a writ de homine replegiando and thus have his claim to freedom tried before a jury.

Indiana in 1816 and 1824 had already made provision for jury trial in disputed fugitive cases, and the de homine writ had long been statutorily available to alleged fugitives in Massachusetts.

In this selective summary of state laws passed before 1830, the principal trend is obvious enough. A desire to prevent kidnapping of free blacks, and especially quasi-kidnapping under the color of law, led a number of state governments to supplement the sketchy, one-sided federal statute of 1793 by imposing their own rules on the rendition process.

Such legislation made recovery of fugitives generally more difficult, and it often had the effect of suppressing entirely the common-law right of recaption. The interference with slaveholders’ rights was at first a more or less unintended consequence of extending protection to free blacks, but increasingly with the growth of antislavery influence, it became a calculated purpose.

The turning point, if there was one, may be said to have come during the 1820s in the aftermath of the Missouri crisis and at a time when militant abolitionism was beginning to emerge as a national movement.

Of course, attitudes and policies with respect to fugitives varied considerably from Maine to Illinois. Nevertheless, by 1830, with nullification of federal law about to become forever identified with South Carolina, the fugitive slave legislation of some northern states was tending in the same direction.

Judicial Involvement

Competing federal and state legislation was only one of the legal complexities of the fugitive slave problem, which also involved the application of common law and constitutional imperative, as well as the extra-jurisdictional reach of slave-state law into free-state communities, the dual status of slaves as persons and property, and a racial order that almost everywhere limited and complicated the freedom of free blacks.

Out of hundreds of separate incidents over the years, each laden with personal drama and each in its own way a dark vignette of American slavery, there arose a variety of issues requiring judicial settlement.

As early as 1795, for instance, the supreme court of New Jersey dealt with the key question of where the burden of proof lay in a contest between a claimant and an alleged fugitive.

At about the same time, in a case involving the famous frontier politician John Sevier, the supreme court of Pennsylvania indicated that physical force could be used in recaption if necessary, “without recurring to any constituted authority.”

A Pennsylvania decision in 1816 held that a child born to a slave after she had fled to Philadelphia could not be claimed as a fugitive. Another in 1819 quashed a writ de homine replegiando on constitutional grounds, thereby closing a common law back door to jury trial for fugitives.

In New York, where use of the de homine writ had been provided for by statute, the state supreme court ruled it unconstitutional just six years later. Meanwhile, various challenges to the constitutionality of the federal law were being turned aside.

In 1816, a federal court in Indiana rejected the argument that Congress lacked the power to enact such legislation. The supreme court of Massachusetts in 1823 rejected the contention that it violated the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures.

And in the mid-1830s, a federal court in New York rejected the argument that it violated the Seventh Amendment’s guarantee of jury trial.

In the Massachusetts decision, Chief Justice Isaac Parker [1768-1830] held that the protection of the Bill of Rights did not extend to slaves because they were not “parties to the Constitution.”

In the Massachusetts decision, Chief Justice Isaac Parker [1768-1830] held that the protection of the Bill of Rights did not extend to slaves because they were not “parties to the Constitution.”

Whatever may be said about its validity, such a pronouncement begged the central question commonly at issue in fugitive slave cases, namely, whether the alleged fugitive was in fact a slave.

It amounted to juridical acceptance of the southern rule that blacks were slaves unless they could prove themselves free. Parker also declared that the Constitution, in spite of its delicate reference to slaves as persons, actually embodied an agreement to treat them as property.

Both doctrines — presumption of slavery and slaves as property — had been implicitly embraced by Congress in the act of 1793, and northern judges were more disposed than northern legislatures to follow its example.

The leading northern court decisions of the time consequently tended to counteract legislative trends by reaffirming the right of recaption, overturning provisions for jury trial, and upholding the supremacy of federal law over that of the states.

In these decisions, one commonly finds the mixture of judicial formalism and moral regret expressed by a Pittsburgh recorder when he returned a fugitive to his master in 1835:

“Whilst, as a man, all my prejudices are strong against the curse of slavery, and all its concomitant evils, I am bound by my oath of office to support the constitution of the United States and the constitution of Pennsylvania, not to let my feelings as a man interfere with my duties as a judge.”

Such decisions also undoubtedly reflected a social conservatism made more resolute by anxiety about the future of the American Union.

The ominous Missouri crisis was still a fresh memory when Andrew Jackson entered the White House in 1829, and during the eight years of his presidency, sectional strains were intensified by the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia, the nullification movement in South Carolina, the emergence of a more radical abolitionism personified by William Lloyd Garrison, the crusade for abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, the bitter struggle in Congress over antislavery petitions, the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies, the beginning of the controversy over annexation of Texas, and an outburst of anti-abolitionist riots across the North…

Prigg v. Pennsylvania

In a good many of the significant fugitive slave cases, no one’s freedom was actually at stake. Instead, the central figures were persons being prosecuted or sued for aiding the escape of fugitives or for kidnapping free blacks.

One such case proved to be especially historic. In 1837, Edward Prigg, acting as the agent of a Maryland claimant, set out to recover Margaret Morgan — not a recent runaway but rather one who for five years had been living in Pennsylvania with her husband and a growing number of children.

At first, Prigg tried to act in accordance with the Pennsylvania law of 1826, but after meeting resistance from the local justice of the peace, he and three associates simply carried the woman and her children off to Maryland.

There followed an indictment for kidnapping and an unsuccessful effort to secure his extradition. In some respects, the whole affair resembled the dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia that had led to passage of the federal law of 1793.

Now, Pennsylvania and Maryland, after decades of complaining back and forth across the Mason-Dixon line, agreed to an arrangement whereby their conflicting interests in the fugitive slave problem would be submitted to the highest judicial authority.

Now, Pennsylvania and Maryland, after decades of complaining back and forth across the Mason-Dixon line, agreed to an arrangement whereby their conflicting interests in the fugitive slave problem would be submitted to the highest judicial authority.

Prigg was extradited, tried, and convicted; the verdict was upheld pro forma by the supreme court of Pennsylvania; and the case was then taken on appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

Prigg v. Pennsylvania, argued and decided during the early months of 1842, might with more accuracy have been titled “Maryland versus Pennsylvania,” or even “Slave States versus Free States.”

For nearly half a century there had been no congressional legislation respecting fugitive slaves. The subject had never been discussed in a presidential message or dealt with in a decision of the Supreme Court.

This long period of detachment was now about to end. Prigg v. Pennsylvania amounted to a resumption of the early movement toward nationalization of the fugitive slave problem that had begun in the Constitutional Convention and culminated in the act of 1793.

[Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was constitutional and superseded state laws, but also stated that states were not obligated to enforce the federal law. This set the stage for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.]

Don E. Fehreenbacher is the author of The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of The United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (Oxford University Press, 2001), from which this essay is excerpted.

Read more about slavery in New York.

Illustrations, from above: Illustration of kidnapping of John Peter Lee in the Anti-Slavery Almanac, 1839; portion of article from the New York Daily Advertiser; header for the kidnapping case in New-York City-Hall Recorder; an 1851 broadsheet warning of kidnappers; and Massachusetts Justice Isaac Parker

Recent Comments