William Sharp was born Leon Schleifer in 1900 at Lemberg in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Lviv, now part of Ukraine), where he attended the Academy for Arts and Industry and continued his studies in Kraków, Poland, before finishing his education at the University in Berlin in 1918.

William Sharp was born Leon Schleifer in 1900 at Lemberg in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Lviv, now part of Ukraine), where he attended the Academy for Arts and Industry and continued his studies in Kraków, Poland, before finishing his education at the University in Berlin in 1918.

After serving briefly in the German army, he stayed on in Berlin and worked as a book illustrator, etcher and painter. He focused on courtroom sketches for the liberal Berliner Tageblatt and the social democratic weekly Volk und Zeit.

As Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party grew in the late 1920s, Schleifer adopted various pseudonyms whilst contributing political cartoons for the anti-Nazi press. Threatened with imprisonment in 1934, Schleifer and his wife Ruth fled to the United States.

On arrival, he adopted the English surname William “Sharp,” reflecting the ferocity of his satire. The couple settled in New York City, living in an apartment on 108th Street in the green residential area of Forest Hills, Queens, until his death in 1961. He became an American citizen in 1940.

Employed by newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst as a courtroom artist, he sketched images of the notorious 1934 Bruno Richard Hauptmann case (the “trial of the century”) for the kidnap and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son.

Published in the New York Daily Mirror, his recordings cemented a reputation as the finest courtroom illustrator of his time. He went on to cover many sensational trials, including those of Alger Hiss who was accused in 1948 of working for the Soviet Union; that of Iva Toguri D’Aquino (a “Tokyo Rose”), an American citizen of Japanese descent, who was convicted of treason after World War II; the 1950 Great Brink’s Robbery in Boston; and the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg who were executed for spying in 1953.

Berlin Sketchbook & Painter of NYC

Berlin Sketchbook & Painter of NYC

Launched in June 1940 by the author and editor Ralph Ingersoll, PM was a left-leaning New York City tabloid newspaper reporting on the social issues of the day. Designed to be a “picture magazine” in a tabloid format (without advertising), the editors turned “against people who push other people around.”

The paper attracted notable writers like Ernest Hemingway and Dorothy Parker and published shots by Weegee (Ascher Fellig – born near Lemberg), Manhattan’s outstanding press and street photographer.

Sharp became involved because of editorial interest in “sketch reporting.” Over seven days in October 1941, PM publishing dozens of pages from his “smuggled sketchbook.”

Drawn in the early 1930s, well before the world became aware of the regime’s gruesome nature, Sharp supplied caricatures of Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels.

He recorded scenes of atrocities had had seen firsthand, evoking the terror created by Hitler’s Storm Troopers (the “conquerors of the streets”) during the Nazi rise to power.

Sharp would go on to work for a multitude of newspapers and journals, and he also took delight in his work as a book illustrator, particularly for Esquire magazine. He produced memorable images for John Hersey’s The Wall (1950), the story of the Warsaw ghetto uprising during the Nazi occupation.

He illustrated Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamozov and Edgar Allen Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination as well as the short stories of Ernest Hemingway and Thomas Mann, the Nobel prize-winning German refugee novelist. He won acclaim for his work on The Diary of Samuel Pepys and on Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone.

As a social commentator, Sharp criticized the ills of American society. Racial inequality disturbed him and in some drawings he addressed concerns about the welfare and treatment of Black Americans, both in the political arena and the legal system.

As a social commentator, Sharp criticized the ills of American society. Racial inequality disturbed him and in some drawings he addressed concerns about the welfare and treatment of Black Americans, both in the political arena and the legal system.

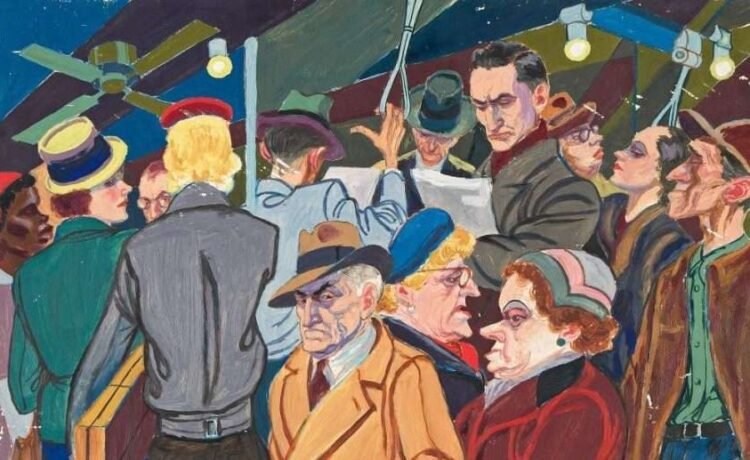

Inevitably, his curiosity and thirst for life drew him to the shadier sides of urban life and the peccadilloes of New York’s streets. The cast of characters was inexhaustible. He also completed a delightful series of works celebrating jazz culture in the 1950s, many of whose key figures lived and performed in Queens. Throughout his oeuvre, the Berlin legacy is unmistakably visible.

Sharp was a political artist, but the message never overshadowed the quality of his work. His eye for detail and touch as a draughtsman guaranteed the creation of striking images that carried unambiguous meaning. His drawings of trials and socio-political cartoons have received ample attention, but his street- and cityscapes from this turbulent period in New York’s history are less well known.

The Great Depression defined the decade of the 1930s, the worst crisis the nation had suffered since the Civil War. Art and politics became entangled. Newspapers and magazines employed artists to produce political cartoons and drawings.

A left-wing periodical like New Masses used the visual arts to advance its socio-political commentary. In a time of hardship, questions about identity and belonging came to the fore. What does it mean to be American? What is the specific characteristic of American art?

Artists and critics tried to define the specific contours of an American art tradition that differed from European settings. In painting, regionalists celebrated rural life of the Midwest with a sense of nostalgia for a “paradise lost.” Social and urban realists focused on harsh urban landscapes.

Some artists concentrated on the alienation of those who were unable to survive in an intensely competitive world; others captured the energy of the city in flux and the resilience of its inhabitants in combating the deprivation they suffered. Creative artists were keen to create an American mode of art.

This is a textbook summary of the era’s cultural developments. This assessment needs refinement as it obscures the fact that immigrants were strongly associated with the creation of New York’s cityscape. Russian Jewish refugees (mostly second generation) and recently escapees from Germany and Austria were amongst the most sensitive artists to evoke life, labor and emotion in the urban environment.

This is a textbook summary of the era’s cultural developments. This assessment needs refinement as it obscures the fact that immigrants were strongly associated with the creation of New York’s cityscape. Russian Jewish refugees (mostly second generation) and recently escapees from Germany and Austria were amongst the most sensitive artists to evoke life, labor and emotion in the urban environment.

Like fellow immigrant painters, Sharp was “obsessed” with depicting the subway, either its stations or from within the moving train itself. These images symbolized the diversity of the metropolis as well the massification and isolation of urban society.

Terms such as patriotism or nationalism in this context are untenable. The quest was another one. How, as diverse communities, can we live together and tolerate one another? How can we forge a common identity as New Yorkers?

Colonial Sand & Stone Company

Sharp also recorded the spectacle of industrial activity in the metropolis. Around 1940 he created an oil painting of the “Colonial Sand and Stone Company,” an image that is clearly linked to the vogue of European Futurism.

Politically, it reflects the clash between two ideologies that had haunted Europe, one that was felt in the American immigrant sphere – Socialism versus Fascism. Although a pleasing picture from an aesthetic point of view, its subject matter seems strangely at odds with the artist’s political views.

Despite the Great Depression, the decade was a time of substantial infrastructure developments in New York with a continuous demand for sand, gravel, and concrete. The Colonial Sand & Stone Company, the country’s largest business of its kind, provided the concrete for New York’s upward and outward expansion, including the Empire State Building, the Rockefeller Center, and Radio City Music Hall, as well as the city’s airports and subways.

Despite the Great Depression, the decade was a time of substantial infrastructure developments in New York with a continuous demand for sand, gravel, and concrete. The Colonial Sand & Stone Company, the country’s largest business of its kind, provided the concrete for New York’s upward and outward expansion, including the Empire State Building, the Rockefeller Center, and Radio City Music Hall, as well as the city’s airports and subways.

In May 1906, at fifteen years of age, Generoso Papa arrived in New York City as a steerage passenger on SS Madonna having left his family’s farming village of Arpaise, Campania, with a handful of dollars and little English.

Having settled in New York, he found work at $3 a week carrying water for a construction crew at the Pennsylvania Railroads East River tunnel. He worked as a laborer on construction jobs for five years while attending to night school at the same time. In 1911, he joined the newly formed Colonial Sand & Stone Company, becoming its superintendent and eventually the firm’s owner.

In 1912, having changed his name to Pope and assumed American nationality, he extended his business interests and founded “Pope Foods,” importing Italian products for the American market.

Food was at the center of immigrant life in Manhattan and essential for the creation of a distinct Italian American identity. Pope’s reputation spread quickly amongst members of the community. Local restaurants, shops, and street markets filled their areas with the taste and aroma of ethnic cuisine, creating a distinct foodscape that gave members of the community a sense of belonging.

Pope then moved his attention to the media. In 1928, he bought the newspaper Il Progresso Italo-Americano (the largest Italian language daily in the country) and doubled its circulation in New York City. Having purchased added papers in New York and Philadelphia, he was the community’s main source of socio-political and cultural information.

By launching a publishing career, he became New York’s leading Italian-born spokesperson and was in touch with high-level civic officials at Tammany Hall as well as the city’s religious leaders. Any political candidate aiming for election needed to secure his approval. As a conservative Democrat supporting Franklin Roosevelt, Pope’s newspapers swung the Italian vote for him.

By late 1921, Italian fascism had grown from a minor political ideology into an aggressive populist movement, targeting left-wingers and liberals who were held responsible for the nation’s decline. The aim was to replace the disarray of democratic government with a powerful paternalistic state.

With ugly scenes of street terror and recurrent parliamentary crises, King Victor Emmanuel III invited Benito Mussolini to form a government in October 1922. The new fascist state set out to dismantle political rights and liberties (internal cleansing) in the name of law, order, and national glory (“Make Italy Great Again”).

Several prominent Americans (including Henry Ford), journalists and academics were charmed by the dictator and admired his interpretation of political leadership. Generoso Pope was one of them.

A staunch anti-communist, Pope was a vocal supporter of Mussolini and his fascist policies. A member of the Fascist League of North America (FLNA), he visited Rome multiple times in the 1920s and 1930s (photographed performing a fascist salute in 1937) and granted private audiences with “Il Duce.”

The latter praised Italian immigrants in America for creating a strong bond between the two countries and Pope’s newspapers printed his words to an American audience. For his support, Generoso received the honorary title of Grand Officer of the Crown of Italy.

Following Roosevelt’s 1932 victory, the press tycoon petitioned the President to declare October 12th a national holiday in honor of Christopher Columbus. The celebration of Columbus Day originated in fascist ideology.

In 1937, spectators (some of them uniformed) at the Parade raised their hands in salute when listening to “Giovinezza,” the Italian Fascist Party hymn. When Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, the authorities incarcerated fascist sympathizers. By then, Pope had publicly distanced himself from Mussolini (although many former associates were arrested).

Pope died in 1950, America’s first self-made millionaire Italian immigrant. At the time of his death he lived at 1040 Fifth Avenue, the later residence of Jaqueline Kennedy Onassis.

His funeral procession to St Patrick’s Cathedral, was led by Irish-born William O’Dwyer, New York City’s 100th Mayor, whilst thousands of people lined Fifth Avenue to pay their respect.

William Sharp illustrations, from above: A detail from “Subway,” ca. 1936; “Der Blitzige Hitler,” 1934 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection); “Jam Session,” 1958/9 (National Gallery of Art); “Evening Repast East River,” 1936; and “Colonial Sand and Stone Company,” ca. 1940.

Recent Comments