It was 1930, during the era of Prohibition (1920–1933). So, it was not unusual when law enforcement personnel caught bootleggers on the Glens Falls-Lake George Road attempting to transport illegal alcohol from Canada to a local speakeasy.

It was 1930, during the era of Prohibition (1920–1933). So, it was not unusual when law enforcement personnel caught bootleggers on the Glens Falls-Lake George Road attempting to transport illegal alcohol from Canada to a local speakeasy.

What was uncommon, however, was arresting a smuggler who tried to sneak a large cache of untaxed contraband, Swiss watches, into the United States.

It was 12:15 pm on October 19, 1930. A car accident had just occurred a few miles south of Lake George on the Glens Falls-Lake George Road (Route 9). The vehicular mishap, a single auto that left the road and struck a concrete abutment, left the driver dead and another man injured.

After the deceased person was removed from the damaged automobile, the surviving occupant was rushed to Glens Falls Hospital. State police then uncovered a fortune in Swiss watches stashed in the hidden recesses of the motorcar. They were concealed inside the upholstery and in a sizeable box fastened to the rear of the fuel-tank frame. The media reported that the illicit haul totaled over 2,000 men’s and women’s Swiss-made watches.

Over the decades, the Swiss have competed with American and several Asian watch-producing countries including Japan. Yet, throughout the decades, Swiss-made watches have generally been preferred over their competition. To protect this reputation strict legal standards governing the use of the “Swiss Made” label exist in Switzerland.

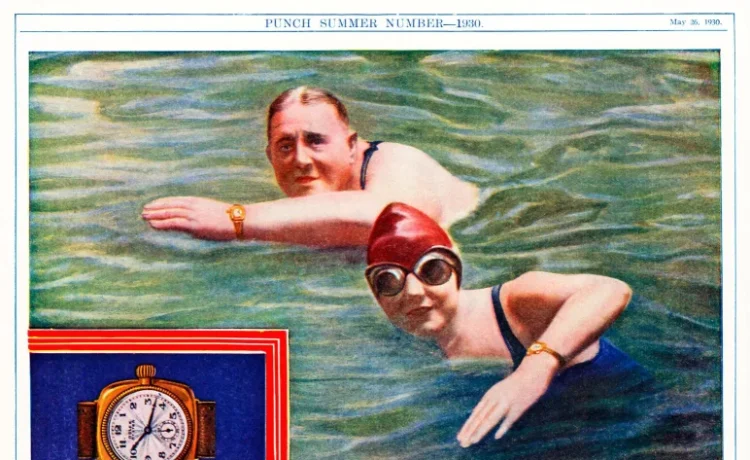

In the early 1930s, one of the most-treasured Swiss watches was the Rolex Cellini Prince. The wristwatch’s avant-garde face design was rectangular in shape rather than round. Great Swiss watchmakers of the Great Depression included Patek Philippe, Tissot, Longines, Rolex, and other notable brands.

Because of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930) and other tariffs, smuggling Swiss watches into the United States became lucrative. That was the case in 1930, when a Brooklyn businessman tried to bring those Swiss watches from Canada into New York City to avoid the tarrifs.

The seized Swiss timepieces were eventually turned over to the U.S. Customs Service. The culprit pleaded guilty and was given a year suspended sentence. The final contraband count confiscated from October 19, 1930, was 2,100 complete watches and the mechanical parts of hundreds more. They had been packed in boxes labeled “electric light bulbs.”

The Brooklyn salesperson was arrested again in September 1931, on that occasion at Rouses Point, a village along Lake Champlain near the New York-Canada border. A colleague and he had 500 Swiss watches when they were apprehended.

“The watch smuggler has gone the way of the chimney sweep, telephone operator, travel agent and other superannuated professions. Or rather, watch smugglers have diversified, as other things – mostly of a chemical nature – have proved to be far more lucrative in the world of smuggling,” says Anthony Peacock, writing in Watch Gecko. “The only watch-smuggling of real note that takes place these days is counterfeiting: a serious and growing problem, with about a million fake watches seized and destroyed every year.”

Read more stories about crime and justice in New York State.

A version of this article first appeared on the Lake George Mirror, America’s oldest resort paper, covering Lake George and its surrounding environs. You can subscribe to the Mirror HERE.

Illustrations, from above: A 1930 advertisement showing a high-quality Swiss timepiece (courtesy Rolex Watch Co.); and an advertisement in the June 12, 1934 issue of the NY Daily News, advertised a sale of smuggled watches secured by agents of the U.S. Government on May 25, 1934.

Recent Comments