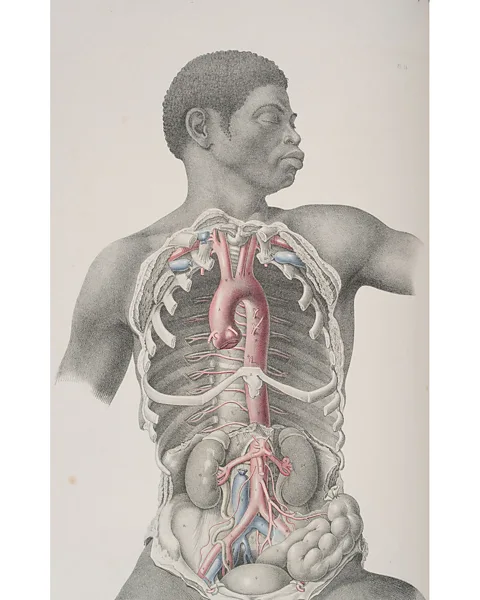

“People perceive that an anatomical illustration is an objective depiction of the human body to the best of the artist’s abilities,” says Gann, which is something that the exhibition seeks to “break apart”. “In truth, they are subject to culture and tastes and artistic movements as any other form of art and illustration.” A nameless black figure in Maclise’s book, thought to be the only black body in anatomical works of the period, is a case in point, having been removed from the edition created for pre-abolition America.

His depiction, notes Keren Rosa Hammerschlag in her 2021 essay, Black Apollo: Aesthetics, Dissection, and Race in Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy, is “notably aestheticised, placing him in dialogue with classical statues such as the Apollo Belvedere, the “high” art productions of Joseph’s brother Daniel Maclise, pictures of black pugilists, and abolitionist imagery from the period.”

Mark Newton Photography

Mark Newton PhotographyWithin a decade of Maclise, Henry Gray’s celebrated Gray’s Anatomy, illustrated by Henry Vandyke Carter, would finally place an affordable resource in the hands of medical students, yet it too was indebted to unclaimed bodies from workhouses and infirmaries. “There is a silence at the centre of Gray’s, as indeed there is in all anatomy books, which relates to the unutterable,” writes Ruth Richardson in The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy. “As mass-produced images, [the bodies of these people] have entered the brains of generations of the living… And nowhere but in Carter’s images do they receive memorial.”

The use of voiceless victims to further medical science endured into the 20th Century. Eduard Pernkopf’s Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy (1937), for example, still used by some surgeons today, features prisoners of war dissected by Nazi doctors working under Hitler’s regime.

Recent Comments