Getty Images

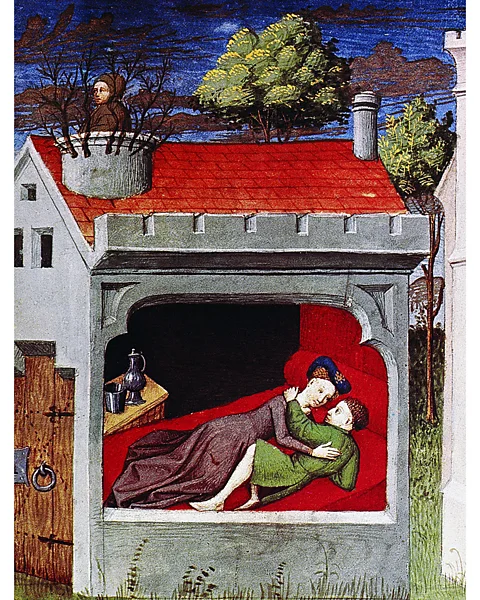

Getty ImagesWritten by Giovanni Boccaccio in the 1350s, this collection of stories deals with sexuality in a way that can still make readers blush – and it has now inspired a Netflix comedy.

Quiz question: which work was described by The New Yorker as “probably the dirtiest great book in the Western canon”? Is it James Joyce’s Ulysses perhaps? After all, that novel was banned for obscenity. Maybe Lady Chatterley’s Lover, also banned? Or the perennially problematic Lolita? Nope, nope and nope. Not even close. How about a collection of short stories written in the 14th Century in the aftermath of the Black Death? For sheer eye-popping smut The Decameron, written in Italian by Giovanni Boccaccio in the early 1350s, leaves its rivals in the shade. It has even left its mark on the Italian language, where the word boccaccesco (we might say “Boccaccio-esque”) can be used to describe something salacious or lewd.

Netflix

NetflixWe’ll come back to the ribaldry in a moment, but The Decameron has far more to recommend it than just its dirty stories. Here is how Boccaccio introduces his greatest work: “My plan is to recount one hundred stories, or fables, or parables, or histories, or whatever you wish to call them. They were told over 10 days, as will be seen, by an honourable company made up of seven ladies and three young men who came together during the time of the recent plague.”

The plague, though barely mentioned after the first chapter, provides the backdrop to The Decameron and gives the work its strange frisson. Its opening passages describe in unsparing detail the horror as the disease takes hold of Florence. Bodies rot in the streets, and a kind of riotous debauchery sets in as the social order is upturned. The constraints that kept men and women in carefully regulated separation fall away as households are destroyed. Outside, with no city officials to keep the peace, violent gangs ride through the town looting and hollering. In the surrounding countryside, unshepherded animals graze to fatness in the unharvested fields.

Why the premise resonates

It is this sudden anarchy that new Netflix comedy series The Decameron takes as its starting point. Thinking of our own recent pandemic, the show’s creator Kathleen Jordan says she wanted to explore how “at times of crisis, the chasm between the haves and the have-nots grows wider”. But in the chaos of Boccaccio’s Florence, with its loosening of rules and hierarchies, Jordan also explores the potential for realignment, for servants to pose as their mistresses and nobles to be cast into servitude.

The show’s setup comes straight from Boccaccio: 10 young nobles flee from the horror of Florence to sit out the worst of the pandemic in a country estate outside the city – a luxurious, sexy, alternative world that bristles in part because of the existential horror happening outside its walls.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat the Netflix series leaves out, however, is actually the meat of the original Decameron. As Boccaccio’s introduction makes clear, his work is a portmanteau of 100 short tales, joined together by the framing story of these young aristocrats passing their time at leisure. Each day when the sun is at its height, they gather in the shade to tell each other stories, and every day a different member of the group will take a turn at being King or Queen – master of ceremonies, basically – who can, if they wish, impose a theme for the day’s storytelling: disastrous relationships, for example, or wives who play tricks on their husbands, or vice versa. Part of the pleasure of Boccaccio’s Decameron is the different layers it keeps in play: us watching them telling tales, making each other laugh, blush, complain, or tell another tale in response.

If you’re thinking that all this sounds a little like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, then you’d be right. Chaucer had certainly read The Decameron – he may even have met Boccaccio on a trip to Italy – and he borrows some of the stories, putting them into the mouths of his own characters. The Reeve’s Tale, for instance, has the same bed-hopping plot as the story that one of Boccaccio’s young nobles tells on Day Nine. Shakespeare, meanwhile, takes another of The Decameron’s tales of sexual mistaken identity – this time a woman deceiving a man in the darkened bedroom – and uses it as the plot of All’s Well That Ends Well.

It’s ‘equal-opportunities’ randiness

One of the things that might surprise a modern audience is the way Boccaccio does not shy away from female sexuality. There is an equal-opportunities randiness at work here. On the sixth day, as the group settle down in the afternoon, they are interrupted by a tremendous racket coming from the kitchen. Two servants, Licisca and Tindaro – a woman and a man – are having a blazing row. The subject: whether or not women are generally virgins on their wedding day. We never get Tindaro’s side of the argument, but we hear plenty from Licisca: “I don’t have a single neighbour who was a virgin when she got married,” she shrieks, “and as for the married ones…” Licisca’s uncensored rant has the female aristocrats in stitches, but when Elissa – the group’s Queen for the day – can finally get a word in edgeways, she slyly pitches the servants’ dispute to the gentlemen of the group: which of them is right? Unhesitatingly, the men side with Licisca. “Didn’t I tell you so?” declares Elissa.

Alamy

AlamyNot that anyone seems to have been in much doubt on the subject of the potency of female sexuality. Take for example the story which one of the men tells on Day Three. A handsome young peasant named Masetto applies for the role of gardener at a convent in the hope that it will provide him with an opportunity to sleep with some of the nuns. In order to get the job, Masetto pretends to be deaf-mute, thinking that no one will object to his presence if they believe that he can’t chat up the young women.

What he finds instead is that, since he is unable to speak, all of the nuns – and even the abbess – begin to proposition him until finally he is exhausted. Forced to break cover, he reveals what has been happening to the abbess, complaining that he simply hasn’t the stamina to keep up with their appetites. The story has a happy ending: the abbess gives Masetto a promotion and draws up a rota so that he can keep satisfying the convent’s needs into his old age. If you’re looking for a moral, Boccaccio is rarely your best bet.

Of course, it is not just nuns who can’t control their lusts. Before the third day is out, one of the ladies of the group has responded with another tale, this time about an abbot who was “extremely saintly in every way except when it came to women”. Quite the caveat! The randy abbot is wildly in love with a local beauty but unfortunately her jealous husband, Ferondo, watches her every move.

With the aid of his monks, then, the abbot drugs Ferondo and transports him to a cell at the monastery. When he awakes, the monks tell him that he has died and gone to purgatory as a punishment for his jealousy. They keep him there for the best part of a year, beating and scolding him, while his wife, pretending to be in mourning, secretly enjoys regular sessions with the abbot. Finally, the monks tell Ferondo that he can return to the world of the living as long as he mends his ways. Relieved and repentant – and once again under the influence of the sleeping drug – he is returned to his village where he passes the rest of his days as an ideal husband. His wife, for her part, never looks at another man again. With one exception: “whenever she could do so conveniently, she was always happy to spend time with the Abbot who had attended to her greatest needs with such skill and diligence.”

Reading The Decameron – with its lustful monks and badly-behaved nuns – something that becomes quickly apparent is that Boccaccio has little respect for religious authority. This did not escape the notice of the Church. When the Vatican first produced their Index of Banned Books in 1559, the Decameron was there on the list. Not that this stopped people from reading it. In fact, the public outcry at this attempt to suppress the work led to a compromise: a censored edition that kept the sex scenes but rewrote the ones that involved members of the clergy, recasting them as ordinary lay people. Thankfully, the changes have not stuck, and modern translations follow Boccaccio’s original text in all its irreverent glory.

Getty Images

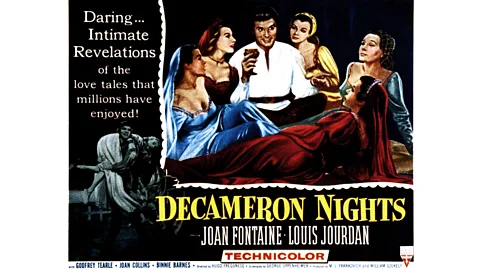

Getty ImagesWhen the Covid-19 own pandemic struck four years ago, Boccaccio’s joyful plague text found itself in vogue, with booksellers running out of stock as simply everyone seemed to be reading The Decameron. The new Netflix series arrives on the crest of this surge in popularity, but it is not the first attempt to harness Boccaccio’s classic into a screen adaption. Some, like Pasolini’s 1971 film, have kept loosely on the right side of being out-and-out pornography; others have very much not. But the best way to experience the sprawling energy of The Decameron is still to enjoy it on the page. Nearly seven centuries after they were written, these earthy, boccaccesco tales still have the power to bring pleasure, consolation, and a little bit of surprise.

The Decameron is streaming on Netflix now.

Recent Comments