Of all the city slickers ever to venture into the 19th century American West, Oscar Wilde towered above the rest, preening like a peacock with his ostentatious wardrobe, his philosophy of art and his knack for spilling printer’s ink across the pages of Western newspapers. In the parlance of the cowboy, Wilde exemplified the “swivel dude,” a gaudy fellow worthy of a second look or a tip of the hat. The flamboyant poet and playwright not only turned heads with his eccentric outfits, but also left Westerners scratching their noggins over his esoteric lectures on “The Decorative Arts” and “The House Beautiful.” For the better part of two months in 1882 Wilde pranced his way across the frontier, a wholly different breed of pioneer.

Arriving in New York City on Jan. 3, 1882, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde spent 51 weeks touring the United States and Canada, traveling 50 of those days west of the Mississippi River. Twenty-seven years old when he arrived, he had accomplished little beyond graduating from Magdalen College, Oxford, self-publishing a play and a thin book of poetry, and ingratiating himself into London’s high society with his quick, sardonic wit. During college and afterward Wilde evolved into both a disciple and a proponent of aestheticism, a philosophy best summarized as “art for art’s sake.” Proponents, or aesthetes as they were called, valued form over function. Aestheticism countered the function-intensive machines of the Industrial Revolution and the Victorian belief that literature and art should provide moral and ethical lessons and restraints on society.

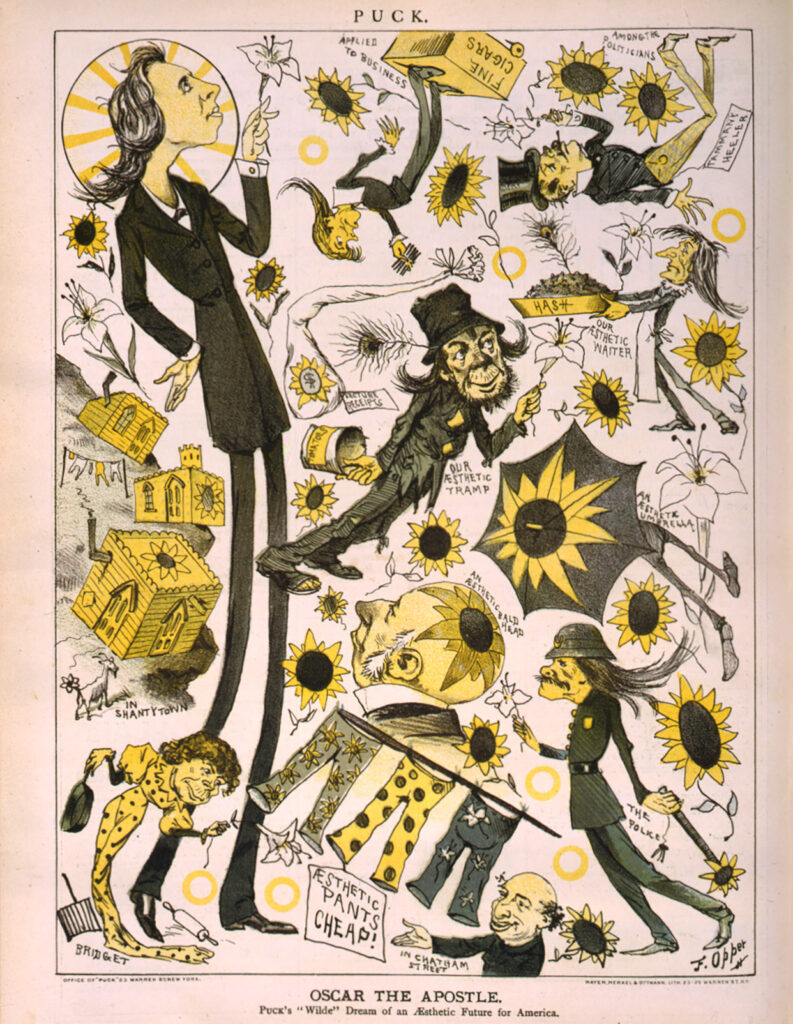

While other aesthetes made greater contributions to the philosophical movement, none was more visible than Wilde, largely due to his extravagant dress and a peculiar fixation on sunflowers and lilies as “the most perfect models of design, the most naturally adapted for decoration—the gaudy leonine beauty of the one and the precious loveliness of the other giving to the artist the most entire and perfect joy.” Wherever he spoke in America, runs on florist shops depleted the supply of those two flowers, as fans and skeptics alike were eager either to laud or mock Wilde with them.

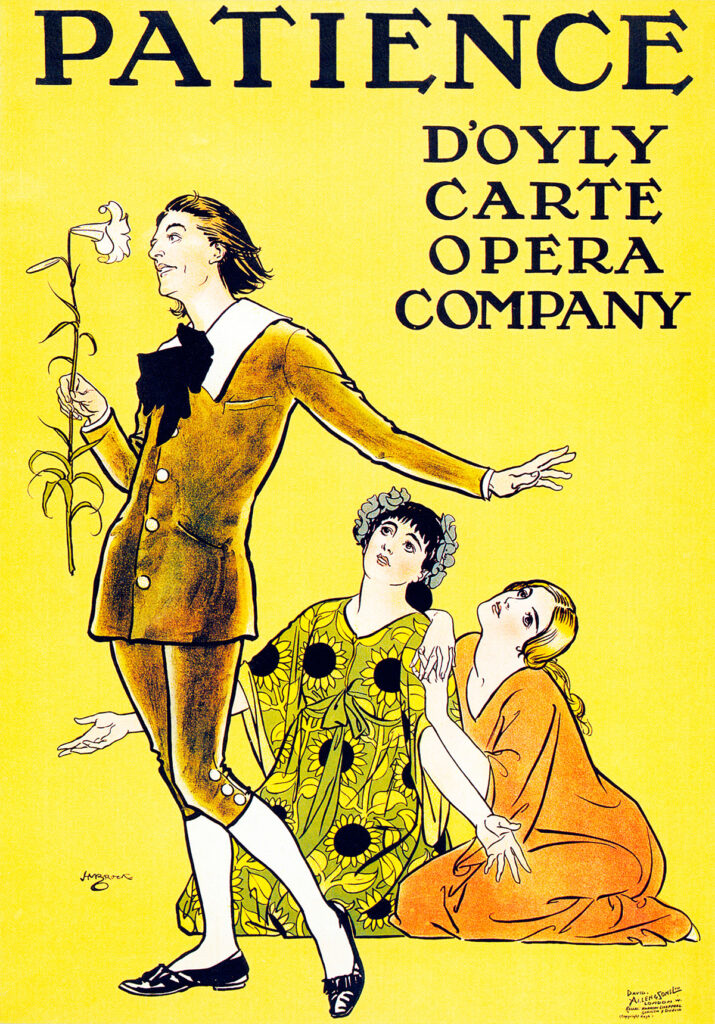

the principles of aestheticism, they might lay the groundwork for an American tour of their related production, ‘Patience.’ Wilde came away with material wealth and name recognition.

(Lordprice Collection (Alamy Stock Photo))

Among the skeptics, dramatist W.S. Gilbert and composer Arthur Sullivan parodied the aesthetes with a “fleshly poet” named Reginald Bunthorne, the lead character of their 1881 comic opera Patience—the follow-up to their hit comic operas H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance. On the back of the duo’s latest success, their producer, Richard D’Oyly Carte, decided to take Patience across the pond to North America. Doubting that Americans would understand the play’s satire, Carte sought an “advance poster” of aestheticism to promote it. Wilde was the natural choice, as Carte was already serving as the poet’s booking manager.

Likely massaging Wilde’s ego with a suggestion his poetry was also popular in the United States, Carte persuaded the Irishman to assume the mantle of the fictional Englishman Bunthorne for a lecture tour. The clincher was Carte’s offer of half the net profits.

What Wilde excelled at most in his young adulthood was self-adoration and self-promotion, often erasing the line between fame and notoriety. When he arrived in New York, the young nation’s biggest celebrity was dime novel hero Buffalo Bill. By the time the aesthete returned to Britain, Wilde—if not eclipsing the future Wild West showman as a household name—had certainly drawn more news coverage than William F. Cody. At very least Wilde was the first celebrity who became famous merely for being famous, launching the superficial celebrity culture that permeates American popular culture to this day.

“lord of the lah-de-dah”

Wilde stood 3 inches over 6 feet. Protruding from his elongated, colorless face was a prominent nose over coarse lips that sheltered greenish-hued teeth, discolored from too many Turkish cigarettes and too few toothbrushes. His thick eyebrows shaded attentive eyes, and a long mop of tawny brown hair brushed against his shoulders. “He looks better in the dark, perhaps” quipped one St. Louis journalist. A portrait of Wilde printed in the competing Leavenworth Times prompted Kansas’ Emporia Daily News to observe, “If it is anything like correct, there will be no chance for Oscar to get a wife in this neck of the woods.”

What Wilde lacked in looks, he made up for with a voguish wardrobe that ranged from dark formal suits to gaudy shirts and cravats in vibrant purples, greens and yellows. For his first appearance west of the Mississippi he chose a more subdued outfit, his trademark knee britches in black over black silk stockings and patent leather pumps with large silver buckles. Above that he wore a white shirt and white waistcoat topped with a long-tailed black coat and white kid gloves.

His presentations, though, were neither as bright nor as entertaining as his attire. Wilde read his speeches in a monotone voice with a verbal quirk accentuating every fourth syllable. In advance of his February tour date in St. Louis the Globe-Democrat reported, “Curiosity to see Oscar Wilde is greater than to hear him.” Following his lecture there to an audience of 1,500 a subhead in the paper’s coverage pronounced, A Large and Fashionable Audience Bored by His Talk on Art. The reporter, like many other Western newsmen, christened Wilde “the lord of the lah-de-dah.” Others just labeled him an “ass-thete.”

After St. Louis and side trips to Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota, Wilde on March 20 took the transcontinental railroad for talks in Sioux City and Omaha before lecturing the philistines of San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose, Sacramento and Stockton. Aboard the westbound train Wilde enjoyed the company of actor John Howson, then traveling to San Francisco to play Bunthorne in the West Coast production of Patience. Whenever Wilde wearied of facing the applause or jeers of spectators who thronged train stations to gawk at the aesthete, he’d send out a costumed Howson to greet the folks instead.

After nine days in California, during which he stayed in San Francisco’s luxurious Palace Hotel, Wilde headed back east, stopping first in Salt Lake City, where a Herald reporter attended his lecture and penned a scathing review:

“What is the attraction about this strange specimen of humanity? Oscar is not handsome and is strikingly awkward; as an elocutionist he violates every rule of rhetoric and is painfully dreary in his manner of expression.…Only in the matters of exhibiting decidedly vulgar front teeth and displaying an abundance of not even wavy hair is he a success.”

Wilde then moved on to Denver, Leadville, Colorado Springs, Kansas City, St. Joseph, Topeka, Lawrence, Atchison and Lincoln before wrapping up on April 29 with a whirlwind tour of five Iowa communities. In June he returned west for appearances in Fort Worth, Galveston, Houston and San Antonio. By the time he ended his Texas swing, Wilde had cleared $5,605, or nearly $170,000 in present-day dollars. That total did not include the money he personally charged admirers to attend their local functions.

Puzzling the Press

Wherever he went, Wilde made time for newspaper reporters, receiving them in his hotel suite after they had properly provided their calling card to his manservant. Describing his audience with the apostle of aestheticism, a San Antonio Light reporter “found Mr. Wilde taking the world easy in his room at the Menger; he was dressed in drab velvet jacket, blue tie, white waistcoat, light drab trousers, scarlet stockings and slippers. A table covered with books, a lemonade—with a stick in it—and a huge bunch of mammoth cigarettes made up the array that confronted our aesthetic reporter.”

Wilde flattered reporters to their faces and then demeaned them behind their backs, prompting Tucson’s Arizona Daily Star to observe, “The average reporter may not have a very exalted idea of art, but he knows human nature too well to stick himself in knee breeches and call it brains instead of brass.” In the end, Wilde and the press used each other—the aesthete to enhance the fame he craved, the reporters to sell papers.

Audiences either revered Wilde for his intellect, even if they didn’t understand it, or ridiculed him for his eccentricities. “Oscar Wilde, the apostle of the beautiful, is here,” The Topeka Daily Capital gushed, “and there is no doubt that he will have a full house. Topeka is essentially aesthetic, and to hear the great exponent of true culture is an opportunity which may never occur again.” Nebraska’s North Bend Bulletin was considerably less flattering in its report of the lecturer’s forthcoming stop in nearby Fremont: “Oscar Wilde is coming. It’s just awful.”

(Library of Congress)

Besides his dry, droll delivery, Wilde’s standard topics on art and beauty seldom resonated with people scratching a living from the earth. For instance, as decorative flourishes in the home the aesthete recommended tiny porcelain cups over their heavier crockery cousins—this to listeners who set tables with often little more than tinware. Further, he prescribed tiled, not carpeted, floors; porcelain, not cast-iron, stoves; and wainscoting, not papered walls. Such advice might have had greater application east of the Mississippi, but out West, to people living in adobe jacals or log cabins, it lacked pertinence.

Less forgivable was lord lah-de-dah’s condescension toward people unable to broaden his fame and wealth, conduct that grated on Western sensibilities. “Oscar Wilde was more bother than all the women who ever rode in a railroad car,” one Chicago-based train conductor recalled. “He had an idea that he was the greatest man America had ever seen.…He was the vainest, most conceited mule I ever saw. He wouldn’t drink water out of the glass at the cooler, but sipped it out of a silver and gold mug he carried with him.”

High Times in Leadville

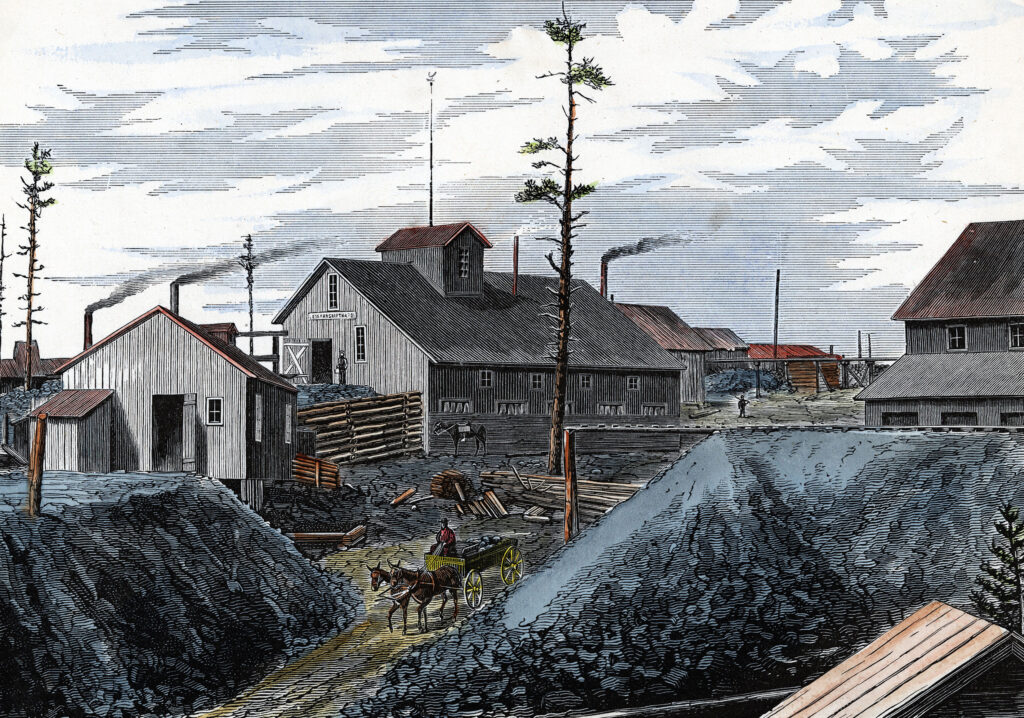

Wilde’s impromptu April 13 visit to Leadville, Colo., endured as the most colorful of the aesthete’s stops across America. Though it was not on his original itinerary, Wilde squeezed in an appearance between lectures in Denver and Colorado Springs after no less a figure than Lt. Gov. Horace A.W. Tabor, the “Bonanza King of Leadville,” offered the poet a tour of his Matchless silver mine.

Wilde recalled the silver boomtown as “the richest city in the world…[with] the reputation of being the roughest, and every man carries a revolver. I was told that if I went there, they would be sure to shoot me or my traveling manager. I wrote and told them that nothing they could do to my traveling manager would intimidate me.”

When he reached Leadville (elev. 10,158 feet) after a bumpy 150-mile, six-hour train ride, he felt understandably lightheaded, nauseous and short of breath. A doctor called to his Clarendon Hotel suite identified his malady as “a case of light air,” or altitude sickness as it is known today. The doctor prescribed medicine and rest while Leadville anticipated his appearance.

The aesthete eventually recovered enough to dress in color-coordinated knee britches, stockings, shirt, fancy cravat, dress coat and a broad-brimmed hat. Before striding across the covered bridge that connected the hotel’s third floor with the ritzy Tabor Opera House, Wilde unpacked his copy of The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, reasoning that if he were too weak to deliver his lecture, he could read passages from it to attendees. What could be more appropriate? he thought, for like the hardscrabble miners in the audience, the great Renaissance artist also worked in silver.

(Denver Public Library)

As the minute hand slipped well past Wilde’s scheduled appearance, the Leadville Daily Herald recalled, “a whole house of curiosity seekers,” some having paid as much as a $1.25 for reserved seats, fidgeted impatiently. When the lecturer did finally show, the Herald reporter wrote, he “stumbled onto the stage with a stride more becoming a giant backwoodsman than an aesthete.” Placing his speech and the Cellini autobiography on the podium, Wilde launched into a variation on his decorative arts spiel.

As the lecture dragged on, the audience grew noticeably restless, so Wilde turned to the autobiography, drawing a reprimand from a boisterous miner questioning why Wilde hadn’t invited Cellini to speak for himself.

“He’s dead,” Wilde explained.

“Who shot him?” replied the curious miner.

Somehow the lecturer made it through his talk without taking a bullet, though the Herald reporter took a potshot at Wilde in print, writing, “The most notable feature of Mr. Wilde’s lecture was the rather boisterous good humor of the audience.”

After the lecture Wilde returned to the hotel to change into more practical clothing and grab a coat for his tour of town and the Matchless. With Mayor David H. Dougan and select Tabor employees acting as guides, the lecturer stepped into the crisp night air, which seemed to revive him. Wilde saw and heard Leadville’s nightlife, a cacophony of drunken carousers, brass bands, tinkling pianos, spinning roulette wheels, screeching women proffering nocturnal delights and boardwalk barkers for saloons bearing such colorful, albeit sometimes misleading, names as the Red Light, Silver Thread, Tudor, Little Casino, Bon Ton, Board of Trade, Chamber of Commerce and Little Church, the latter of which boasted a mock chapel as its entrance.

The tour was an eye- and earful for Wilde, who followed his guides into Pop Wyman’s rollicking saloon. Rumor had it Wyman had killed several men in his younger years and carried a change purse made from a human scrotum. Wilde complimented the saloon owner for a sign over the piano reading, Please Do Not Shoot the Pianist; He Is Doing His Best, calling it “the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across.” He later elaborated on the message, writing, “I was struck with this recognition of the fact that bad art merits the penalty of death, and I felt in this remote city, where the aesthetic applications of the revolver were clearly established in the case of music,

my apostolic task would be much simplified.”

(Pikes Peak Library District)

From Wyman’s the mayor had the party loaded in wagons and driven 2 miles to the Matchless, where mine superintendent Charles Pishon accompanied Wilde down shaft No. 3 in a metal ore bucket lowered 100 feet into the pitch black by a cable-and-pulley system. A dozen miners greeted their guest, showing Wilde silver in its natural state and letting him drill the start of a new shaft they dubbed “The Oscar.” Quipped Wilde, “I had hope that in their grand, simple way they would have offered me shares in ‘The Oscar,’ but in their artless, untutored fashion they did not.”

The mining soiree ended with an early morning supper, Wilde wrote tongue in cheek, “the first course whiskey, the second whiskey and the third whiskey.” By the time those gathered had emptied all the bottles, their foppish guest had impressed his hosts for his ability to hold liquor without any visible signs of inebriation. Finally re-emerging from the mine, Wilde returned to the hotel for a brief rest before boarding a train to Colorado Springs to deliver a speech just 14 hours later. He was no worse for the wear.

Heading for Home

On writing about his experiences out West, Wilde largely mocked the “barbarians” he had striven to enlighten. “Infinitesimal did I find the knowledge of art west of the Rocky Mountains,” he recalled, illustrating his criticism with the story of a miner who had struck wealth beyond his education and turned to culture to flaunt his riches. After ordering a replica of the Venus de Milo from Paris, Wilde wrote, the nouveau riche miner “actually sued the railroad company for damages because the plaster cast…had been delivered minus the arms. And, what is more surprising still, he gained his case and the damages.”

Americans likewise found fault with Wilde as he prepared to leave the States that December. Wrote one acquaintance, “He is guilty of all sorts of petty meanness, such as perpetually begging cigarettes from acquaintances and never offering any himself; eating dinners with indefatigable industry at other people’s expense, sneaking out of paying cab fares; and ‘working’ his friends shamelessly for whatever he can get out of them.”

Yet, for all his snobbery, Wilde still found a noble quality among the Westerners, observing, “The West has kept itself free and independent, while the East has been caught and spoiled with many of the flirting follies of Europe.”

By the time he left New York City for home, Wilde had traveled some 15,000 miles through 30 of the 38 United States, leaving in his wake more than 500 major newspaper features and countless Westerners scratching their heads at what they had seen and/or heard. His fame briefly surpassed that of Buffalo Bill, at least until Cody started his Wild West show the next year. Nine years after returning home Wilde finally attained the literary notoriety he’d craved with publication of his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Unlike other city slickers who visited the American West, Wilde conned more folks than outwitted him, and he left with more money than he had yet earned. Despite the Irish peacock’s biting condescension, his annoying arrogance and his numerous faults—or perhaps because of them—Wilde could claim the title of the Wild West’s all-time slickest dude.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Wild West magazine. For further reading, author Preston Lewis recommends Wilde in America: Oscar Wilde and the Invention of Modern Celebrity, by David M. Friedman; Oscar Wilde Discovers America (1882), by Lloyd Lewis and Henry Justin Smith; and Oscar Wilde, by Richard Ellmann.

Recent Comments