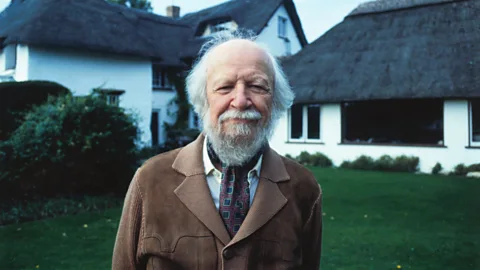

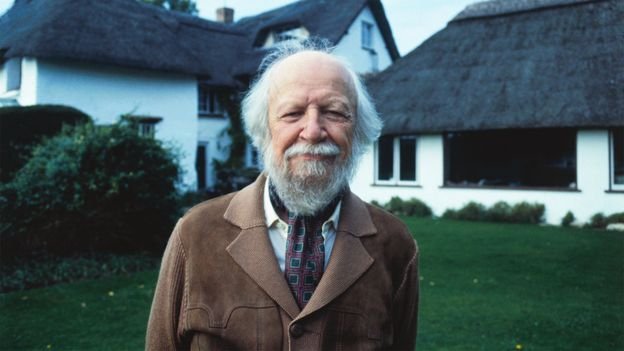

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWilliam Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies was first published on 17 September 1954, and is now recognised as a classic. In History looks at how Golding’s story of English schoolboys and their descent into barbarism narrowly escaped being thrown in the bin.

“Write what you know” is advice often given to aspiring authors, and Lord of the Flies is a spectacular example of how clichés can still contain essential truths. A teacher at a boys’ school who had witnessed first-hand the inhumanity of World War Two, William Golding condensed this knowledge and experience into his debut novel, a deceptively simple tale of shipwrecked boys reverting to savagery on a desert island. Its subversion of a familiar plot went on to resonate with generations of readers, and serve as a grim warning that the evils of Nazi Germany could be repeated anywhere.

Golding was about to turn 43 when Lord of the Flies was first published. His big idea was a sinister 20th-Century reimagining of The Coral Island, RM Ballantyne’s 1857 tale of derring-do in which a group of shipwrecked British schoolboys civilise a desert island, making it a playground for fun and games. Much of his original manuscript was handwritten on exercise books during school time. He even worked on the novel during lessons, while his pupils were occupied with their textbooks. A few of them were tasked with counting the number of words he’d written per page.

In 1953, Golding sent his novel to nine publishers, all of whom rejected it. Undaunted, he offered the manuscript to Faber and Faber, one of the most prestigious London firms. It was picked up by Charles Monteith, a junior editor who had only worked at the publishing house for a few months. The signs were not promising.

Absurd and uninteresting

He told the BBC’s Bookmark in 1984: “Already there was one particular sort of thing I could spot, and that was the tired, weather-beaten old manuscript that had been around a lot of publishers before it reached us, and this was very much that. It was a large yellowing manuscript with the pages beginning to curl, and one or two stains for teacups that were put on them, or wine glasses, and drops of coffee and tea spilled, and was bound in rather depressing, hairy brown cardboard, and there was a short, formal covering letter.”

One of the publisher’s professional readers had already delivered her written verdict on Golding’s manuscript, dismissing it as an “absurd and uninteresting fantasy”. Along with a circled R for “reject”, she wrote: “Rubbish and dull. Pointless.”

Fortunately for Golding, Monteith gave the book another go, and decided to save it from oblivion. He said: “I had a look, and I must say I wasn’t at all attracted by the beginning of it, but eventually I went on and got absolutely caught up by it. And from then on, I said ‘we must take this seriously’.”

He persuaded Faber and Faber to publish the book, but Golding first had to make some significant changes to the text. Also, its original title, Strangers from Within, had to go. According to Golding biographer Professor John Carey, the original manuscript was a religious novel that was “drastically different from the Lord of the Flies most people have read”.

Capacity for evil

Speaking on 2012 Arena documentary The Dreams of William Golding, Carey said that the author became deeply religious following World War Two, when he had served on a Royal Navy destroyer, but his editor Monteith’s revisions excised these elements. “Golding concedes, concedes, concedes, until what came out is a novel that is secular; it’s not assuming any supernatural intervention,” he said.

Golding’s experience of war gave him a deep sense of man’s capacity for evil and a disillusionment with the idealistic politics of his early life. Lord of the Flies was his warning that the Nazism that engulfed Germany in the 1930s could happen in any civilised country. Speaking on The South Bank Show in 1980, he explained how the war transformed his attitude to human nature.

“It simply changed because, bit by bit, we discovered what the Nazis had been doing. Here was this highly civilised race of people who were doing, one gradually found out, impossible things. I remember, in those days, saying to myself, ‘Yes, well, I have a Nazi inside me; given the right circumstances, I could have been a Nazi.’

“Bit by bit, as I discovered more and more what had gone on, that really changed my view of what people were capable of, and therefore what human nature was. So that political nostrums, if you like, seemed to me just to fall flat on their face in front of this capacity man had for a sort of absolute evil.”

Although Lord of the Flies had been a critical success, it wasn’t until the publication of the US edition, and particularly the paperback in 1959, that Golding became an international bestselling author and started to earn large amounts in royalties. The success allowed him to quit his teaching job and become a full-time writer. “I didn’t like the systematic side of teaching; I’m not a very systematic person,” he admitted to Bookmark in 1984.

On his status as a literary late bloomer, he said that his breakthrough came when he realised he had to stop imitating other writers. “It wasn’t until I was 37, I suppose, that I grasped the great truth that you’ve got to write your own books and nobody else’s, then everything followed from that,” he told Monitor in 1959.

One young fan of Lord of the Flies was the novelist Stephen King, who borrowed the book from a mobile library after requesting something about “the way that kids really are”. He told Arena in 2012: “I was completely riveted by the story from the very beginning because it was like a boys’ story, the ones that I was accustomed to. The difference was the boys were real boys – they acted the way that I understood boys acted.”

A storyteller through and through

King went on to set several stories in the fictional town of Castle Rock, which he named after Jack’s mountain fort in Lord of the Flies. From cult 1990s backpackers story The Beach to teenage cannibalism drama Yellowjackets via the obligatory Simpsons parody, Lord of the Flies has become a pop culture touchstone. The book was twice adapted for film in 1963 and 1990, and a BBC television adaptation by screenwriter Jack Thorne is currently being filmed in Malaysia.

For Golding, the secret of his success was itself almost a cliché. He told Bookmark in 1984: “I am at bottom and at top, too, a storyteller through and through. What matters to me is that there shall be a story with a beginning, a middle and an end.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

Recent Comments