The first schools in New York City were established in 1805 as the Free School Society, run by Quakers, and later by Baptist groups who renamed the school system, The Public School Society.

The first schools in New York City were established in 1805 as the Free School Society, run by Quakers, and later by Baptist groups who renamed the school system, The Public School Society.

The Catholic Church dissuaded participation in The Public School Society believing it to be anti-Catholic, and with Irish Catholic immigration on the rise in the 1830s, the pressure to include their involvement in schools led to the establishment of the NYC Board of Education (BOE) in 1842.

Schools were under local control by town school boards. The Public School Society schools were ultimately converted to the universal public school system in 1853. African Americans were, however, not able to access these schools until after 1827, when the New York legislature passed a law for the abolition of legal slavery, the first state to do so.

The first school established to educate African Americans in Brooklyn in 1827 was the New York African Free School. It began as a one-room schoolhouse with forty students, mainly enrolling children of slaves, and was later incorporated into the New York public school system and renamed Colored School No.1.

In 1896, Plessy vs. Ferguson upheld the “separate but equal” decision, and in 1899 a similar ruling by New York state courts decided that it was legal to refuse admittance of a “colored child” to a “white public school.”

Although this provision was repealed in 1938, theoretically making segregated schools illegal, no real desegregation occurred and schools remained segregated in New York.

Between 1940 and 1960, Black and Puerto Rican immigration to NYC was met with rampant racism. Federal Housing Authority’s guidelines upheld residential segregation with redlining practices, whereby neighborhoods were rated on a scale, with lower ratings given to communities with higher shares of black residents. Banks refused loans to black home buyers,and landlords discriminated against black renters to avoid the risk of lowering a neighborhood’s rating.

Between 1940 and 1960, Black and Puerto Rican immigration to NYC was met with rampant racism. Federal Housing Authority’s guidelines upheld residential segregation with redlining practices, whereby neighborhoods were rated on a scale, with lower ratings given to communities with higher shares of black residents. Banks refused loans to black home buyers,and landlords discriminated against black renters to avoid the risk of lowering a neighborhood’s rating.

Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods and schools became overcrowded, yet the school zoning lines remained in place. The BOE’s answer to overcrowding in schools in Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods was to implement part-time school days and the old school facilities continued to deteriorate.

A few months after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court ruling that declared dual educational systems unconstitutional, Kenneth Clark, a psychologist whose research was used by the NAACP in the Brown case, concluded that de facto segregation in NYC schools led to inferior education that resulted in psychological damage to black children.

A lesser known finding from Clark’s research, highlighted by Heather McGee in her recent book, is the harm done to white children. Clark notes that students in the majority group learn “prejudices of our society and are also being taught to gain personal status in an unrealistic and non-adaptive way.”

His research was initially met with backlash, but he was able to convince then school Superintendent William Jansen to support a study, “The Status of the Public School Education of Negro and Puerto Rican Children in NYC.”

The NYC BOE tasked the Public Education Association to conduct the study, which essentially confirmed Clark’s findings: schools that served Black and Puerto Rican students were overcrowded, buildings were in deplorable conditions, teachers were inexperienced and many were substitute teachers, poor academic achievement was the norm, and students of color were disproportionately placed in special education classes.

The BOE acknowledged segregation was a problem in the city schools and established a committee, The Commission on Integration, to evaluate the report’s findings and to propose an integration plan.

Six sub-commissions presented their recommendations to the BOE between 1956-1957, but in 1958, the Commission’s Final Report found limited changes, citing lack of funding and “professional misunderstandings” of the recommendations.

Seven years later, The Harlem Parents Committee documented that “after another seven years of studies and surveys, new programs and ‘pilot projects,’ reports and recommendations, consultations and conferences, demonstrations, counter-demonstrations, boycotts and negotiations, policy pronouncements and progress reports, we find ourselves essentially no further along that road in the fall of 1965 than we were in the fall of 1958.”

In fact, segregation had increased, with the number of “X” school (those with an elementary school population of 90% or more of Black and Puerto Rican students and junior high school with a population of 85% or more) increasing 17% in the two years after the Commission’s report.

Buildings were left in their dilapidated states, and the BOE was unwilling to alter zoning to achieve integration. Clark, who later served on the New York Board of Regents, was bitterly disappointed at the failure to deliver on many promises.

Residential segregation, property tax-based school funding, boundary lines, and resource decision-making by white administrators unfairly relegated black students to segregated schools with inferior conditions and less qualified teachers.

In 1958, “The Little Rock Nine of Harlem,” a group of mothers, boycotted Harlem junior high school, claiming their children were not receiving a quality education. As a result, four of the parents were found guilty of violating the state’s law on compulsory education.

Supreme Court Judge Polier tried the case of two of the other parents, dismissed their case and issued a landmark decision upholding the parents’ rights to their children’s equal education. Her decision charged the NYC BOE with offering inferior education to black students but stopped short of alleging de facto segregation.

The BOE appealed the Polier decision, spurring protests to remove board members, which did not materialize. The Harlem 9 provided a model for school boycotts for the next 15 years.

Like most of the country, the decades following Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) were a time of concentrated desegregation efforts. However, unlike desegregation in the South, New York City schools never faced a citywide desegregation lawsuit and were never court-ordered to desegregate, and to date, have not achieved racial/ethnic integration.

Ten years after the Brown decision, the BOE announced the Free Choice Transfer integration plan, a future desegregation plan (the Princeton Plan), and a rezoning plan. These plans were designed to integrate black and white schools by pairing imbalanced schools and provided busing to transfer students between neighborhoods.

White backlash quickly ensued; white residents established the Parents and Taxpayers organization (PAT) to oppose the plan.

Civil rights activists, frustrated over continued stymied integration efforts, led one of the biggest Civil Rights Movement boycotts to protest segregation and inequity in education. In 1964, over 464,000 students participated in the boycott.

Civil rights activists, frustrated over continued stymied integration efforts, led one of the biggest Civil Rights Movement boycotts to protest segregation and inequity in education. In 1964, over 464,000 students participated in the boycott.

In response, the PAT staged an opposing protest where more than 10,000 white parents marched to fight integration efforts. In the end, protests and threats against NYC officials who feared the threat of white flight led to the abandonment of desegregation efforts.

In response to fierce resistance to integration on the part of white residents, black and Latino civil rights leaders in NYC led the charge towards local control, and in 1969 the State Legislature decentralized the city schools by dividing the city into 32 community school districts (CSDs, also called “Districts”) and transferred control from the mayor to local school districts.

Local districts had the power to elect community boards and local superintendents who governed elementary and middle school; high school remained controlled by NYC BOE. This system, with many modifications, lasted until 2002 when Michael Bloomberg became mayor, successfully lobbied the state legislature and gained control of NYC public schools.

This win allowed the mayor to appoint school chancellors and members of the Board of Education and gave him the power to close schools.

In 2007, Supreme Court decisions in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District struck down voluntary integration programs that assigned students to schools according to their race. Subsequently, the few schools in NYC that previously achieved racial/ethnic balance by using race in admissions became majority (>50%) white.

Thus, initiatives to decrease segregation using race/ethnicity in admissions were essentially abandoned under Bloomberg’s administration. Bloomberg transformed school admissions, which were previously based on geographic proximity, to a school choice model where families select schools and rank their preferred school choices.

The process was intended to diminish inequity in the city by allowing students to apply to schools anywhere in the city and thus leave segregated, poor quality neighborhood schools. However, this posed several problems, not the least of which was the challenges facing the schools left behind.

Moreover, along with school choice, Bloomberg expanded admissions methods based on screening tests, grades, interviews, behavior, attendance, auditions, and demonstrated interest — exclusionary practices that served mostly middle-class white and Asian students. Without an eye towards equity, these reforms targeted middle-class families to draw them to NYC public schools.

Bloomberg selected attorney Joel Klein in 2002 as school chancellor. He closed roughly 150 ineffective schools and, in their place, encouraged and aided in opening charter schools by offering them free space in public school buildings.

Magnets, conceived to promote voluntary integration, fell out of favor, and magnet grant funding ceased in 2010. The city embraced a market oriented choice solution, without equity policies to prevent segregation of opportunities.

New York City, 2014 to 2021

Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014. His policies did not focus directly on meaningful integration efforts in the first years of his administration, typically avoiding the term “segregation” and instead favoring “diversity.”

De Blasio’s approach remained hands-off in making concerted efforts towards integration, arguing residential housing and historical racism were intractable problems complicating the issue in schools.

His focus centered on improving all schools and offering parents more choices, believing that these would promote voluntary integration. Part of his agenda represented a reversal of the charter school expansion under his predecessor, preferring to turn around ineffective schools over closing them.

DeBlasio campaigned to curtail charter expansion, and in his first year made good on the promise; the DOE rejected several charter co-location applications.

Pressure by charter school operators resulted in Governor Andrew Cuomo approving a law in 2014 to offer charter schools free space or pay their leases in private space. New charter schools continue to be approved, but at a slower rate than under Bloomberg’s administration.

After the publication of the CRP report in 2014, the NYC Council held a hearing on school segregation that led to the passage of the School Diversity Accountability Act in 2015, requiring the NYC Department of Education to report demographic data and enrollment information by grade level in specialized programs, such as gifted and talented programs.

At the state level, under pressure to promote school integration, the Socioeconomic Integration Pilot Program (SIPP) was created to provide $1.25M in grants between 2015-2018 to help schools achieve racial, ethnic and socioeconomic balance in their enrollment.

A similar version of this plan was presented at the federal level but dismissed by the education department under President Donald Trump. Despite initial resistance to integration efforts, due to the CRP report, media coverage of it and public pressure, in 2015, Mayor de Blasio signaled his willingness to address the state of segregation in the city and initiated the NYC Department of Education (DOE) plan, “Equity and Excellence for All.”

Consistent with de Blasio’s idea that creating great schools is a panacea to segregation, the plan entails several programs to improve all student outcomes, such as a Pre-K for All program and expanded Advanced Placement courses in high schools.

The plan also sets priorities and goals to create diversity in its schools. For example, it specifies when a school is considered racially representative, defines inclusivity to include students who speak dual languages and students with disabilities, improves the school selection process, and expands diversity in admissions pilot programs, among several other important goals.

NYC deserves credit for the steps it has taken, and the plans outlined in “Equity and Excellence for All” to increase and support diversity in schools.

As part of the plan, the DOE established the School Diversity Advisory Group (SDAG) to make recommendations on racial and socioeconomic diversity goals and examine admissions policies that perpetuate racial/ethnic isolation.

Two reports laid the foundation for the city’s diversity plan. The reports presented short-, medium-, and long-term goals that encompass all school levels.

The SDAG based the goals on the 5Rs of Real Integration set forth by Integrate NY, a youth-led advocacy group: race and enrollment, resources, relationships, restorative justice, and representation.

Among the recommendations in the reports, the SDAG recommended eliminating gifted and talented programs, mirroring school demographics to that of the city and promoting socioeconomic integration.

A significant shift in integration policy occurred in 2018 when de Blasio hired school chancellor Richard Carranza, formerly of the Houston and San Francisco schools. Carranza signified a decided change in the administration’s stance towards integration. Carranza openly made the issue of integration a priority, gaining him both praise and criticism.

His first move was to tackle head-on the elimination of the Specialized High School Admissions Test. In 2019, he strongly supported a plan to eliminate the test and repeal the Hecht-Calandra Act mandating the admissions test at 3 of 8 specialized schools.

Wealthy donors and some Asian advocacy groups strongly opposed the plan. Ultimately the plan never made it to the legislative floor after the Assembly’s education committee voted against it.

This essay was drawn from “NYC School Segregation Report Card: Still Last, Action Needed Now!” (June 2021) by Danielle Cohen, of the UCLA Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

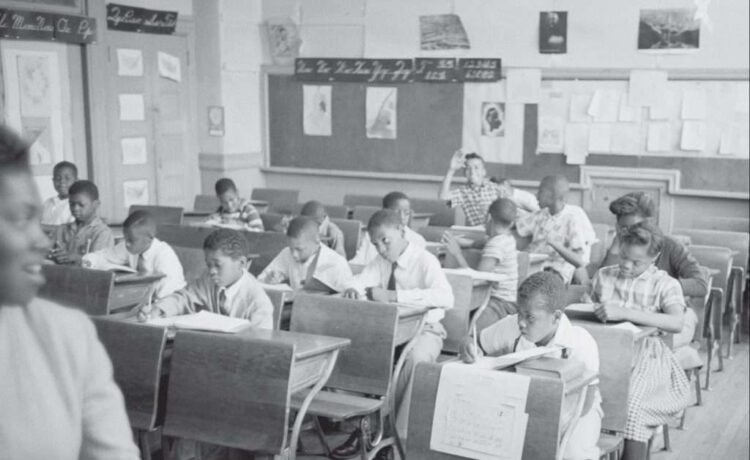

Illustrations, from above: A 1922 lithograph of the African Free School No 2 after an original by student Patrick H. Reason; Black school children, 1957; and school boycott picketers march across the Brooklyn Bridge to the Board of Education in 1964.

Recent Comments