Lucasfilm Ltd

Lucasfilm LtdIt may be set a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but Tony Gilroy’s Star Wars series takes a key plot from a real robbery masterminded by Stalin in an Imperial Russian city. And Andor has as much to do with our world as it has with Stalin’s.

It has all the makings of the perfect heist.

The scheme takes place far from the imperial seat of power, on the wild fringes of an empire almost too vast to comprehend. Fuelled with revolutionary zeal, the plotters are a rag-tag outfit of men and women that includes thieves, murderers and turncoats. Their prize? A treasure chest of cash that can fund ever-more-ambitious missions against the hated ruling elite.

If you watched the first season of the Star Wars spin-off TV series Andor, you’ll recognise this plot as one of the high points. Over three episodes, anti-hero Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) and his band of accomplices hide out in mountain passes on the planet Aldhani, fine-tuning an audacious smash-and-grab from an Imperial garrison which is storing the wages of an entire sector.

The real-life theft that inspired it was also a long, long time ago, just not quite so far away.

Alamy

AlamyIt took place in Yerevan Square in what was then the imperial Russian city of Tiflis, now the Georgian capital Tblisi, on 26 June 1907. A shipment of cash for the city’s Russian state bank branch, amounting to some 300,000 roubles ($1m at the time), was stolen by a gang of robbers linked to the Bolshevik revolutionary movement. Using bombs and guns, the gang left a scene of utter devastation in their wake; some 40 people were killed and dozens more injured. The news of the brazen daylight attack made headlines across the world.

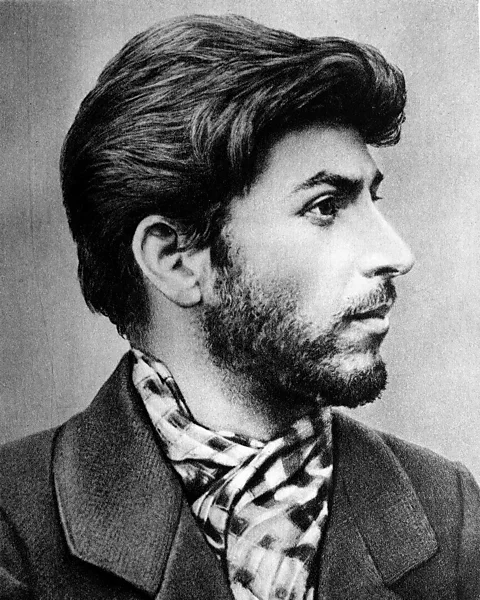

The heist was the brainchild of a charismatic cobbler’s son-turned-revolutionary called Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili. He was a gifted public speaker, an ex-seminary student, a romantic poet rumoured to have left a string of broken hearts in his rakish wake. He often went by the name “Soso” (which he had used when writing poems for local publications), though in years to come he would become far better-known – and feared – as Joseph Stalin.

Yes, the troubled outlaw beloved by Star Wars fans everywhere is based in part on one of history’s most notorious mass murderers, as the series’ creator, Tony Gilroy, has acknowledged. “If you look at a picture of young Stalin, isn’t he glamorous,” Gilroy said in an interview in Rolling Stone in 2022. “He looks like Diego!”

Lucasfilm Ltd

Lucasfilm LtdStalin took Russia from its war-ravaged imperial decline to a nuclear-armed superpower in just three decades, but also presided over a reign of authoritarian terror that starved, executed or imprisoned millions of its own citizens. Countless books had been written on his cruel years in power, but very little on his early years. Writer Simon Sebag Montefiore saw a gap, and began rifling through archives in post-Soviet countries to try and separate the truth from myth, and tell the little-known story of Stalin’s early life.

A gangster and a killer

In 2007 – a century after the infamous heist in Tiflis – Young Stalin was published. It delved into the early life of the Soviet Union’s dictatorial leader. “Should the life of a black-hearted ogre, a mass murderer who was the wickedest of the 20th-Century’s monsters, be quite so entertaining,” asked a review in The Observer at the time.

One person who read Young Stalin was Gilroy. The writer and producer, who had scripted the first four Bourne films and the Andor-precursor film, Rogue One, was planning a TV series that would explore Cassian Andor’s journey from casual thief to rebellious figurehead. The true story of a revolutionary movement on the far fringes of a real empire gave Gilroy his source material. “Literally, I’m the classic old white guy who just can’t get enough history,” Gilroy said in Rolling Stone. “The last 15 years, I’ve been reading all non-fiction.” He added that Young Stalin was “an amazing book” and that its account of the Tiflis bank robbery was an “incredible movie sequence”.

Did Sebag Montefiore ever think to himself, ‘Here’s the perfect setting for a Star Wars spin-off,’ when he was researching his book? “No, I didn’t ever think that when I was toiling in the archives in Moscow and Tbilisi,” he tells the BBC. “But I did think that there was something pretty elemental about the life of Stalin, especially before 1917. It was a fascinating story, partly because no one knew about it.”

The Tiflis heist was reported around the world and funded the revolutionaries’ movement for years, says Sebag Montefiore. “Lenin and the whole Bolshevik Party lived off that money until the [1917] revolution.”

Lucasfilm Ltd

Lucasfilm LtdSebag Montefiore says that the young Stalin and the troubled Andor bear striking similarities: “A young man from nowhere with a revolutionary ideology, and a fight against a huge empire,” the writer says. “I did think there was something interesting about the secret life of someone in that situation. That’s basically what Tony Gilroy has focused on in Andor.”

Stalin was, of course, not the only figure fomenting turmoil in Tsarist Russia, and Andor fleshes out other characters with attributes from the young Georgian’s contemporaries. Among Andor’s co-conspirators in the Aldanhi heist is Karis Nemik (Alex Lawther), an idealist writing a high-minded manifesto for the emerging resistance, similar to Bolshevik Leon Trotsky’s polemics amid the opulent decline of Romanov rule.

Stellan Skarsgård’s character, Luthen Rael, is an analogue for Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader who was able to form a powerful movement from unlikely bedfellows. A wealthy art collector, Luthen’s precise manners in front of his gilded customers hide an uncompromising hatred of the empire and a restless desire to fund a growing resistance. In Cassian’s talented, taciturn thief he sees a useful tool; Lenin saw the same in Stalin. “In 1911, people said to Lenin, ‘Why are you using this guy? He’s a gangster. He’s had people killed. He was involved in all these bank robberies,'” says Sebag Montefiore. “And Lenin replies, ‘He’s exactly the type we need.’ Stalin could edit a paper. He could write and could read. And he was also someone who could arrange a hit on somebody and arrange a bank robbery. That was what Lenin talked about: some people were tea drinkers, and other people were thugs, Stalin could do both, and that’s why Stalin won in the end.”

The birth of an empire

The research into historical rebellions – Gilroy has said he studied other revolutions while writing Andor, as well – has no doubt helped create the show’s oddly realistic feel. Andor feels more down to earth than anything the Star Wars universe has shown us before, if you’ll excuse the occasional spaceship roaring overhead, or an alien or two sitting in the local bar. There are flashes of mundane detail rarely scene in big-budget sci-fi. People complain that Andor’s mother Maarva’s (Fiona Shaw) house is always too cold. Security officer Syril Karn’s (Kyle Soller) petulant intensity even extends to tailoring his uniform to make him look smarter than his contemporaries. The Imperial Security Bureau hoping to root out the emerging rebellion is a nest of competing ambitions that feels as real as anything in a historical drama – or in everyday office politik. There are fewer blaster-toting Stormtroopers than there are in the Star Wars films, and more sadistic, trenchcoated officers who would have been right at home in the Tsarist secret police, the Okhrana, or its Soviet replacement, the Cheka.

“In the past, Star Wars movies drop us in at a very big moment,” says Walter Marsh, an Australian writer who praised Andor’s grown-up worldview in The Guardian in 2022. “There’s the big climactic battle, or Luke Skywalker’s heroic journey, and they’re these big themes of good versus evil. But as any historian will tell you, wars and empires and revolutions don’t start and end overnight, and there’s always this bigger backstory. There’s this sort of long tail. It takes years for that kind of colonial rot, those systems of control, to set in.”

Andor shows the corruption and brutal entitlement found at every layer of autocratic regimes: the guards drinking in a brothel while they’re supposed to be on duty (and prepared to shake down anyone they don’t like the look of); the prison industrial system that requires constant additions even if the new prisoners have done nothing wrong; the subtle sabotage of ethnic pilgrimages to sacred land that is earmarked for imperial development. And with authoritarianism on the rise around the globe, Andor has as much to say about today’s world as it does about Stalin’s.

“When the show came out I think I was pleasantly surprised to see a story in that universe that was familiar, but which also approached this question of empire that’s been so central to the whole franchise, but was never actually tackled in a really nuanced and human character-driven way,” Marsh tells the BBC. “It’s all well and good to have a big, evil Sith Lord achieve global, universal domination. But how does power assert itself on the street level, from one human to another?

Getty Images

Getty Images“The Empire is this huge grinding, unthinking machine, but it’s also a very human thing,” Marsh continues. “Who are the people that find a place and thrive in those systems?” He remarks that in the original films the Imperials were little more than blank-and-you-miss-them pantomime villains: “British guys in suits getting choked by Darth Vader at some point, who are just fiddling with buttons in the background.”

Andor’s strength is its “three-episode arcs that showed us the kind of death by a thousand cuts that it takes to achieve this sort of social, political and economic dominance”, says Marsh. “The converse of that is it shows all the ways in which that kind of oppression inspires pushback and resistance in all kinds of different ways.”

From hero to villain?

The new season, which begins on Tuesday 22 April, will develop the rebellion’s story as it rushes towards the events seen in Rogue One: the scenes of brutal Imperial reactions to a demonstration shown in the trailer evoke the Tsarist crackdown on a St Petersburg march in 1905, which was a slow-burning contributor to the Bolshevik revolution.

“The scavenger who becomes a passionate revolutionary leader is kind of fascinating,” says Sebag Montefiore of the troubled Cassian Andor. “That’s a great trajectory, because that’s exactly what Stalin did. And it’ll be interesting to see how deep Gilroy uses that – how far he goes to create a character with both heroic and villainous features.”

George Lucas’s original film trilogy rooted the rebellion in the classic good-guys-versus-bad-guys dynamic of countless Saturday matinee cliffhangers, the resistance modelled after anti-Nazi opposition in occupied Europe. The rebels of Andor inhabit a much more compromised reality; like real-life revolutionary movements, they are much more complicated than the ones we usually see on screen. Luthen, Andor’s Lenin proxy, considers it with chilling deliberation in one of the first season’s standout scenes: “I’m condemned to use the tools of my enemy to defeat them. I burn my decency for someone else’s future. I burn my life to make a sunrise that I know I’ll never see.”

As Sebag Montefiore notes, the revolutionaries themselves knew deep down that if they took power, they themselves would have to use repression as a tool; they would become what they once despised. “Lenin himself said: ‘A revolution without firing squads is meaningless.'”

Andor season two is available on Disney+ from 22 April.

Recent Comments