Indigenous to the port area of New York, the double-ended ferry was a quick adaptation of steam power. Until the advent of the steam ferryboat however, regularly scheduled ferries in that city and around New York State occurred by sloops, periaugers, and rowboats.

Indigenous to the port area of New York, the double-ended ferry was a quick adaptation of steam power. Until the advent of the steam ferryboat however, regularly scheduled ferries in that city and around New York State occurred by sloops, periaugers, and rowboats.

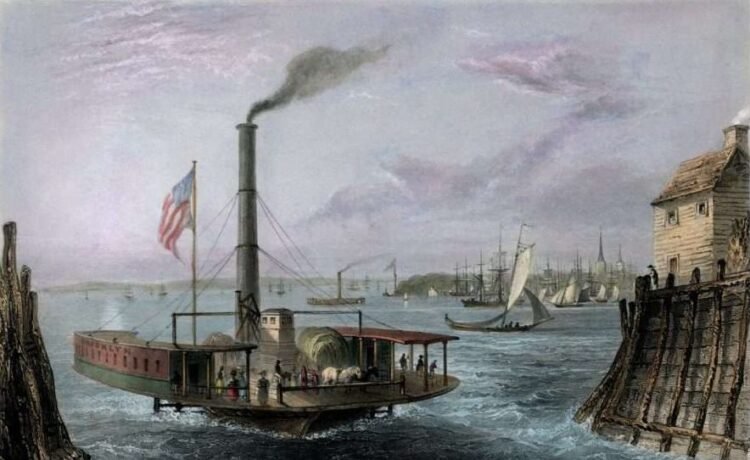

After Robert Fulton‘s successful use of steam power with his Hudson River Steam Boat (later Clermont), innovators realized the potential steam power had for ferrying passengers, and steam service soon became a routine and expected feature of life in the city of New York and its environs.

Original designs and characteristics took place under the guidance of Fulton and John Stevens, who, along with other builders, designed the double-ended ferry.

Robert Fulton launched the first double-ended ferry in July 1812, with the construction of the twin-hulled Jersey. Built by New York City’s Charles Brown Shipyard, the 80-foot-long ferry-boat transported passengers over the Hudson River.

Fulton’s design featured a twin-hulled vessel equipped with a 5-foot draft and a 30-foot beam. The draft allowed easy maneuvering over water. A platform between hulls held machinery, passengers, and cargo.

Fulton’s design featured a twin-hulled vessel equipped with a 5-foot draft and a 30-foot beam. The draft allowed easy maneuvering over water. A platform between hulls held machinery, passengers, and cargo.

Fulton placed the paddlewheel between hulls, mainly to avoid direct contact with floating ice. He situated the rudders in the same space, one forward, one aft of the paddlewheel. Equipped with fore and aft rudders and a double-ended hull, the ferryboat could travel to and fro across the river without turning.

This characteristic gave the vessel type the name “double-ender” and differentiated it from other sidewheel vessel types on the Hudson River and Long Island Sound, powered by the same engine types, had different hull and deck configurations, and had only the single stern rudder.

The Nassau, also built by the Charles Brown Yard, in 1814, retained the twin-hull configuration begun by Fulton, but featured a passenger cabin on the main deck.

Jersey and Nassau remained the only two ferryboats operated by Fulton. After Fulton’s death, former associates added another twin-hulled ferryboat, William Cutting, to the fleet in 1827.

Following visits to the United States in the 1820s, Frenchman Jean Baptiste Marestier wrote an eyewitness account of the Fulton-type ferryboat.

The boats, according to Marestier, had platforms between 72 and 79 feet long. The engines rested on the platform center. The paddlewheel rested in front of the engine. The paddlewheel contained eight buckets eight feet in length, two feet in height. Boiler dimensions averaged 18 feet long, 7 feet wide, and 7 feet high. At the end of each platform sat a cabin.

Because ice had a tendency to disrupt the twin-hulled paddlewheel’s motion, the Union Ferry Company, an outgrowth of Fulton’s ferry line, finally dispensed with twinhulled designs in 1833, opting for single-hulled configurations, which more effortlessly sliced through ice.

Latter-day New York City ferryboats retained two Fulton designs: a sloping main deck amidships to each end (caused by the paddlewheel shaft’s placement above the sheerstrake of the hull) and the characteristic double end.

John Stevens (1749-1838) is credited for the prototype of the single-hulled New York City ferryboat. He launched Hoboken, a 98-foot steam-powered double-ender, on May 1, 1822. The ferryboat ran between Hoboken and Manhattan on the Hudson River.

Keeping two characteristics of Fulton’s early design, the characteristic double-end, and a sloping main deck from amidships to each end, the boat featured a single hull and a sidewheel port and starboard.

Keeping two characteristics of Fulton’s early design, the characteristic double-end, and a sloping main deck from amidships to each end, the boat featured a single hull and a sidewheel port and starboard.

To protect the sidewheels, Stevens extended the main deck. The addition, including paddlewheel sponsons, provided additional room and loading capacity to the boat. Not intended for oceanic passage, the vessel’s design was adapted to the interior waters of New York Harbor.

The demand for ferryboats increased as the boat proved its reliability. The corresponding economic growth in Manhattan and surrounding areas (New Jersey, Brooklyn, and Staten Island) further increased ferryboat demand. New York City’s population in the 1800s numbered around 100,000.

By 1824, six ferryboats serviced the city’s population of 200,000. By 1860, 70 ferryboats serviced nearly 1,176,000 New Yorkers. Some ferryboat companies carried up to 5,000 passengers a day.

Into the 1830s, overall ferryboat size increased. Stevens’ ferryboat line built Fairy Queen in 1826. One hundred forty-nine feet long, the boat measured 26 feet wide with a 6-foot draft. The boat featured a vertical walking beam engine with two paddlewheels.

Fairy Queen had cabins in the hull, accommodating up to 100 passengers. The boat had a bar on board, and during the summer crewmen stretched an awning over the boat from end to end. A helmsman operated a rudder tiller, steering with the help of a pilot who stood at the forward end of the vessel.

In 1836 the Union Ferry Company operated three new ferryboats. On heavily traveled routes, the company added the 304-ton, 155-foot-long Brooklyn, the 155-foot-long New York (23-foot beam, 9-foot draft), and the diminutive Olive Branch (89 feet long, 23-foot beam, and 8-foot draft).

Besides these three boats, Union Ferry operated three other ferryboats ranging in size from 100 to 125 feet in length, 145 to 184 in tonnage.

By the 1840s, shipbuilders all across New York City built double-enders. William H. Webb (1816-1899), noted builder of sailing ships, built three double-enders for the city. Wallabout and New York, sister ships, measured 94 feet long, 23 feet in beam, and 9 feet draft.

The third ferry, Williamsburg, built in 1846, measured 115 feet long, 26 feet in beam, and 10 feet in depth. Each of the boats featured a vertical beam engine with a walking beam. These boats operated on the East River.

The third ferry, Williamsburg, built in 1846, measured 115 feet long, 26 feet in beam, and 10 feet in depth. Each of the boats featured a vertical beam engine with a walking beam. These boats operated on the East River.

The Staten Island ferryboat Hunchback, built by Jeremiah Simonson in 1852, featured an upper cabin, making it the first double-decked ferryboat in New York Harbor. The wooden housing built to enclose the walking beam gave the boat a lumpish appearance, hence the name.

Another Staten Island ferry was the Southfield, built in 1857 for the New York and Staten Island Ferry Company’s route from Staten Island to Manhattan by way of New York Harbor.

The wooden double-ender was 200 by 34 feet, with an overall deck length over guards of 210 by 50 feet. The first 30 feet of hull at each end consisted of solid timber for navigating through ice floes in winter. She was converted to a gunboat by the U.S. Navy during the Civil War.

The 700-ton Atlantic, 177 feet long with a overall deck length of 190 feet, had a beam of 32.5 feet. Built in 1857, the New York Times called Atlantic the “largest and most perfect ferry-boat ever constructed.” The Atlantic featured a hull designed to plow through ice.

Another boat, John S. Darcy, also built in 1857, measured 191 feet in length, 33 feet in beam, and 11 feet in depth, and was for a time the largest ferryboat in the New York City area.

Because some ferries serviced less-traveled locations, many were small. The ferryboats Ethan Allen and Commodore Perry (527 tons) measured 144 feet in length and 33 feet in beam.

The New Jersey Railroad and Transportation Company operated John P. Jackson for ferry service between Jersey City and New York City. The 860-ton vessel, built by the Devine M. Burtiss Shipyard, measured 192 feet end to end, with its deck measuring 210 feet stem to stern.

The ferry had a 36-foot beam, a 12-foot depth, and a draft of 5 feet 5 inches. The frame was of white oak, chestnut, and other hardwoods fastened together by copper spikes/bolts and treenails. Its single-cylinder, vertical-beam engine measured 46 inches with an 11-foot stroke. The paddlewheel had a 21-foot diameter and featured 18 buckets.

The archetypal ferryboat design established by Fulton and Stevens changed little over the years. Most builder concerns centered around keeping foot passengers separated from wagons and other cargo.

Early configurations accommodated wagons near the center of the boat; enclosed cabins provided passenger room and space. Later ferryboat construction kept this configuration, but added a cabin above the main cabin.

Early configurations accommodated wagons near the center of the boat; enclosed cabins provided passenger room and space. Later ferryboat construction kept this configuration, but added a cabin above the main cabin.

An 1880 description of a double-ender states:

“The ferry-boats of New York are double-enders, sharp and swift, with side wheels. the deck highest amidships and dropping about 2 feet at the ends in a gradual curve. They are all of one general type, varying only in size.

“The machinery is stowed away in the hull as much as possible. The engine is low pressure condensing, is often built with horizontal cylinder and piston, has a long stroke, and acts quickly.

“A narrow house rises in the center of the deck to shelter the machinery and cover the stairways to the hold, and on each side of this the deck is open for 10 feet, in order to allow horses and wagons to pass from end to end of the boat.

“The cabins for passengers are outside of the two gangways, one on each side of the boat, and extend two-thirds of the length, each cabin being in turn divided nearly in two by the wheel-house, which rises through it and leaves only a hallway 3 feet wide between the forward and after halves of each cabin.

“A roof covers the whole of the cabin, engine-house, and spaces between for teams, and the pilothouses are on this roof, one at each end of the boat. A portion of the deck at each end is clear of structures of any kind, except the posts and chains needed to prevent the passengers and teams from crowding each other overboard while in the stream.

“These boats are an important feature of the business life of New York city. They run across the North and East rivers at numerous points, and from the city to Staten Island, day and night, at intervals of from 5 to 30 minutes, according to the magnitude of the travel on each particular route.

“A large boat will carry 400 passengers and about 50 teams with wagons on a single trip. In construction of this class of boats the New York builders have attained special excellence.

“The hulls are strongly but lightly framed with oak and chestnut and planked with oak, yellow pine being used for the rest of the vessel except the houses and the decking, which are of white pine and spruce, with cherry, black walnut, etc… in the joiner work of the cabins.

“They cost from $50,000 to $90,000 each, according to the size of the hull and the luxury of the cabins. The Jersey ferry-boat Princeton, of 888 tons, built in the census year, was one of the large class.

“She was 192 feet long, 36.5 feet beam, and 12.5 feet deep in the hold, and to build her it required 52,000 feet of oak, 10,000 feet of chestnut, 103,000 feet of white pine and spruce, and about 10,000 feet of yellow pine. Her machinery weighed 130 tons. Complete the boat cost $85,000.”

Iron straps provided longitudinal support for most wooden-hulled, shallow-drafted ferries. Copper fasteners, commonplace by the 1860s, held strakes below the waterline together, while iron fasteners served the same purpose above.

At either end of the hull was a rudder, and depending on the direction traveled, one rudder acted as a bow, locked in place with a lock-pin, while the other acted as the steering rudder and provided direction.

Winter ice created hazards for the pilot and his boat. Fulton and Stevens had some success with ice, each approaching the hazard differently. Fulton placed the paddlewheel in the center of the two hulls, but ice between the hulls created handling problems.

Winter ice created hazards for the pilot and his boat. Fulton and Stevens had some success with ice, each approaching the hazard differently. Fulton placed the paddlewheel in the center of the two hulls, but ice between the hulls created handling problems.

Stevens’ single-hull configuration pushed the ice out of the boat’s path, and if caught between ice floes, compressed the ice downward, away from the hull. As a safety feature, Stevens placed cork inside the hull for buoyancy.

Boats operating in the harbor faced another hazard: marine borers. Coppering, or sheathing, protected the hull from borer infestation. The combination of sheathing, pitch, horse hair, cloth, or other materials extended the life of the vessel’s hull.

Ferryboat coppering usually occurred several months after construction was completed, allowing for exterior strake expansion. Sheathing could then occur without strain or tear by further expansion.

Vertical-beam engines powered most early double-ender ferries. But because space in the hold of a double-ender was of little value and deck room was critical, the inclined marine engine, which occupied the hold and left more deck room, was accepted by many ferry companies for later vessels. However, in the late nineteenth century the walking beam engine still remained the more usual type.

The inclined engine was designed in 1839 by Charles Copeland, its patent issued in 1841. The placement of the inclined engine in the hold affected the beam-to-width ratio of inclined versus walking beam engine vessels, with the former being much beamier.

Boiler locations varied from boat to boat, some positioned deep in the hold, others located near the paddlewheels. Wood originally provided heat for steam, though coal replaced it as a primary heating source in the early 1830s. As one would suspect with wooden vessels, fire proved an immediate danger during operation.

In 1858, the Williamsburg ferry, operating between Manhattan and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, “adopted… every precaution… to guard against fire, the boilers being quickly felted, and the decks and wood-work around the boilers and chimneys protected by facings of zinc,” according to the New York Times. Fire protection for most ferries probably mimicked the Williamsburg.

As passenger traffic increased, builders in the 1850s included a second cabin above the main cabin. This addition commonly appeared on long-distance service, i.e., Staten Island ferryboats. The promenade, or upper deck, supported the upper cabin and the fore and aft pilot house, and provided additional passenger space.

As passenger traffic increased, builders in the 1850s included a second cabin above the main cabin. This addition commonly appeared on long-distance service, i.e., Staten Island ferryboats. The promenade, or upper deck, supported the upper cabin and the fore and aft pilot house, and provided additional passenger space.

The hurricane deck sat atop the promenade deck cabin. Generally, three pilot house patterns appeared in New York City. A freestanding circular house and a freestanding square house usually appeared on single-decked ferries. A rectangle backed by an upper cabin is normally associated with double-decked boats.

The general configuration of New York City ferryboats remained the same for decades. Until the late nineteenth century, most were sidewheelers, the propeller models appearing in the 1880s.

Design evolution focused on increased size and space. Never as ornate as Hudson River or Long Island Sound steamers, these boats provided ferry service to thousands of commuters. The design is still visible in modem-day ferries.

This essay is excerpted with minor editing for clarification from Target Investigations in Connection with the New York and New Jersey harbor Navigation Project, May 2004, prepared for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District, by Andrew D.W. Lydecker and Stephen R. James, Jr. of Panamerican Consultants, Inc.

Illustrations, from above: James and John Bard’s painting of the Nassau ca 1814; 1814 colorized advertisement for the New-York and Brooklyn Ferry (note early double-ended design); George Richardson’s “The Ferry at Brooklyn New York,” 1838; The East River in 1853 from Brooklyn showing an arriving ferry (Brooklyn Historical Society); James Bard’s illustration of the J.P. Jackson, 1860; and the double-ended paddle wheel ferry Middletown, built in 1864.

Recent Comments