On a cool, moist, spring evening in 1904, the outspoken lawyer and idealist Charles Frederic Adams (1851-1918) was traveling from his home in Brooklyn, by trolley and on foot, to a Milton Literary Society dinner in Manhattan. (He feared riding in automobiles.) But when crossing at an intersection, he was struck by a car and injured his back and scalp.

On a cool, moist, spring evening in 1904, the outspoken lawyer and idealist Charles Frederic Adams (1851-1918) was traveling from his home in Brooklyn, by trolley and on foot, to a Milton Literary Society dinner in Manhattan. (He feared riding in automobiles.) But when crossing at an intersection, he was struck by a car and injured his back and scalp.

The driver of the vehicle stopped briefly, then sped off as a police officer tried to give chase. But scrupulous about obligations, Charles left the hospital he was taken to, and continued on to his dinner engagement. Only when he became ill there, would he let his friends help him home, where he took a few weeks to heal.

That accident was perhaps Charles Adams’ most dramatic, ever, run-in with a machine. But it was far from his first or last encounter with “machines.”

In speeches, letters to newspapers, and proposals advocating reform, he railed most of his adult life against political-party hierarchies — the so-called “machines” and “bosses” who, behind the scenes, influenced parties’ selections of nominees for elections.

He felt they block voters from choosing the “best” candidates, or even seeing good candidates on the ballot. He also felt they fostered crude partisanship: With little to choose from among boss-favored candidates, voters simply try to defeat the “wicked” other party.

Most readers and listeners of Charles knew about scandals and corruption associated with Tammany Hall — which served at times as the Democratic Party’s executive committee in New York City.

Yet, for Adams, its corruption was secondary to the the perverse “system of nomination which,” he wrote, “gives the potential boss his opportunity. Blackmail and bribery come later.” With bosses’ back-room powers to “support” nomination, and patronage, decisions, office-seekers were tempted to pay the boss a little something for his favor.

According to a contemporary biography in The Public: A National Journal of Fundamental Democracy and History in the Making (1910), Adams always tried to avoid, not just partisanship, but accepting any “shibboleths,” whether in politics, religion, law, or even science.

That is, he distrusted accepting fashionable, ready-made, us-versus-them distinctions. He felt every person and viewpoint should be judged on its own merits.

From the outside, his actions applying this ideal could look like flip-flopping. For example, as a member of the Young Men’s Democratic Club in 1884, he endorsed the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland, for President. But later he joined reformist movements like the Citizens’ Union, which nominated candidates they thought had merit, regardless of party.

From the outside, his actions applying this ideal could look like flip-flopping. For example, as a member of the Young Men’s Democratic Club in 1884, he endorsed the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland, for President. But later he joined reformist movements like the Citizens’ Union, which nominated candidates they thought had merit, regardless of party.

In 1893, at a large Citizens’ Union rally, he supported reform-minded, retired judge William J. Gaynor, for Mayor. But regular Democrats also liked Gaynor, who won; so in 1894, Adams encouraged the traditional democrats and the Kings County Independent Democrats to reconcile.

This pattern of his working with or turning away from, different parties or groups at different periods, based on what he considered best in context, was a repeated theme in Charles Adams’ political life.

An International Perspective

Charles Frederic (or “Charles Frederick”, as he also wrote it) graduated in Law from Harvard University in 1871 — a typical career path for a young man of his era from a wealthy, established family.

His father, William Newton Adams, was born in Virginia, with Virginian ancestors dating back to the 17th century. Charles’ grandfather was a West Indian merchant; his grandmother was a sister of navy Commodore John Thomas Newton.

Less common was Adam’s birthplace in 1851: Santiago, Cuba. His father William was serving there as American Consul at the time. Earlier he’d been in business in Venezuela and married Maria Del Carmen in 1844. The couple was concerned about political instability and left Venezuela with their (then) one child for Cuba.

Charles began life in Cuba, then was sent to the U.S. at age 10, to get a rigorous education at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. He polished up skills in four languages, English, Spanish, French, and Italian, which he’d use to advantage later.

He joined a distinguished debating club, later known as the Milton Literary Society (the same Society he was headed to, in 1904, the day a car hit him). At that

club, Charles met a number of future notables, including New York Reform Club founder Horace E. Deming, and the first directing head of what later became IBM, Charles R. Flint.

Meanwhile, Charles’ father moved to Brooklyn himself in 1865 to be nearer his children. He was successful in business there — until things went badly in the 1870s. Charles’ mother died of cancer in 1871.

Then, during the financial Panic of 1873, William lost a great deal of money. When his own health began failing, he was “advised to travel.” On the last of his journeys, in 1877, he died at sea, on board a steamer heading to New York from Cuba.

Charles Frederic was admitted to the New York Bar in 1872. After a period as a law clerk he was hired by Coudert Brothers, an important law firm specializing (well into the 20th century) in international law. With Charles’ language skills, he was called on for a time to represent the firm in Paris.

Perhaps influenced by living his childhood overseas, Adams empathized with island territories — such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico — which had been ceded to the U.S. from Spain.

He became, by 1900, an outspoken “anti-imperialist”; so working at Coudert Brothers was a balancing act for him. On the one hand, he pleaded before the Supreme Court on behalf of the government, in the “Insular Cases.” These argued that not all protections of the Constitution automatically applied to the new territories, at least in regard to applying tariffs.

On the other hand, in a speech to the Social Reform Club in New York in 1900, Adams quoted international lawyer and statesman Elihu Root, distinguishing between technical points of tariff law, versus the “moral right” of the islands’ peoples to the “essential safeguards” afforded in the Constitution (like due process) — “not because these provisions [have been enacted for them], but because they are essential limitations inherent to the very existence of the American Government.”

Adams’ solution to balance his legal work with his powerful scruples was to negotiate an unusual arrangement with Coudert Brothers. It allowed him, in his words, “to refuse any professional service I objected to,” e.g., if he could not abide by the morals of a case.

In return, he received a comparatively low salary, relative to his skills and experience. He reasoned that if his salary was less than another lawyer might have earned, he willingly “gave back the difference for [my freedom].”

Alternating Career Steps

Charles Frederic Adams’ day jobs alternated between periods at a law firm, and other periods serving governments, at various levels, in appointed positions. On his own time, he was almost always supporting causes — ethical, political, and economic — that he was passionate about.

In 1884, Adams left his first stint at Coudert Brothers, to accept a series of federal government positions in Washington DC. He first served as Clerk in the Civil Service Commission, and as a sometime Acting Chief Examiner.

According to his biographer in The Public (1910), Adams then served successive Secretaries of the Interior “as a member of the law board which passed on appeals to the Secretary from the Commissioners of the Land, Patent, Pension and Indian offices.”

In another job change, 1890, the biographer wrote, the “Secretary of State appointed him, because of his familiarity with foreign languages and his scholarship generally, to edit the debate proceedings for the First “Pan American Conference”.”

When his Washington work finished in 1892, the Coudert Brothers law firm welcomed Charles back. He and his wife Henrietta, whom he married in Washington, settled in Brooklyn. Probably encouraged by the law firm, Charles applied for standing to plead cases before the Supreme Court, and was approved by the court later that same year.

Adams continued practicing law at Coudert Brothers until November, 1905. Brooklyn’s new Borough-President-elect, Bird S. Coler, then appointed him Borough Secretary for a four-year term.

Adams had long admired Coler, and even supported Coler’s run for Governor in 1900. Adams’ Borough Secretary duties ranged from routinely signing approvals for public works to serving as, apparently, Coler’s communications assistant or advisor.

This led to an anecdote recounted in the Brooklyn Citizen: Members of the Board of Alderman were “mystified,” one day, by a letter they received, in Coler’s name. There’s no way, thought the aldermen (correctly), that Coler wrote all the Latin phrases, classical allusions, and complex sentence constructions in that letter.

After that term ended, Charles returned another time to law practice, in 1910. There, he continued (with a lengthy break for a lecture tour) until his last government appointment in 1914. From June 1914, until his death in 1918, he was Assistant Tax Commissioner for Brooklyn.

An Idealistic Reformer

Labels for Charles Frederic Adams’ lifelong efforts on behalf of causes have included “Lecturer” or “Politician.” One obituary called him a “disciple of Henry George”—advocate of an economic theory called “single tax.” All are accurate.

But at least as important was his creative brainstorming, about ways reform could be practically implemented. For example, he didn’t merely advocate for workers to have financial protection for their retirement, or during “periods of depression.” He devised and experimented with a real scheme to make this doable, without depending on taxation.

First, he called it (writing in a letter in the New York Times, 1878) a “Working Man’s Tontine” (a kind of annuity). In 1880, he created a legally incorporated

entity called “Trustees of the First Savings Endowment Fund,” and published its legal charter in the Times, to attract interest. Poorer folks could put in just a dollar a year.

Probably to help sustain the fund, by attracting bigger-paying philanthropists, the organization next became “The Brotherhood of the Commonwealth” in 1904, and acquired the trappings of a “fraternal order.” That organization continued on after Adams’ passing, and had 2,500 members by 1919.

Similarly, he did not just critique existing nominating and electoral systems in his lectures and extended Letters to Editors (compare today’s Op Eds). He concocted alternatives.

For example, on several, successive days in 1897, The Brooklyn Citizen published his “An Experiment in Nominations” for mayor of New York. It was a noteworthy early example of voter polling. But its format was a scheme Adams would continue developing, and propose for actual elections.

For example, on several, successive days in 1897, The Brooklyn Citizen published his “An Experiment in Nominations” for mayor of New York. It was a noteworthy early example of voter polling. But its format was a scheme Adams would continue developing, and propose for actual elections.

The published experiment included a blank, cut-out form, for readers to write-in ranked preferences for each of (a) their preferred political party, if any, for the next mayor; and (b) their preferred candidate for mayor.

The form asked readers to mail their completed forms to Adams, via an address provided. If this were a real nomination, the top-ranked candidates for the top-ranked parties, which the polling identified, would become the names and parties printed on the election-day ballots — with some space for write-ins.

It amused a reporter, however, a few months later, when Charles ran a similar experiment at a lecture about primary election reform. Conducted at a “crowded” meeting of the Brooklyn Philosophical Association, wrote the reporter, “Adams, who is a man somewhat under the medium height, with grey hair and a grey mustache which he twirls and eats continually,” explained his system and handed out the sample ballots.

The result was intended “to show the workings of the new system. It did. Almost every party under the sun was represented [in the write-in spaces], and there was an alarming number of candidates [written in] from Charles F. Adams himself… to [as literally spelled out by someone] ‘The man that will all wase support an honist Roepublic’.”

“If Mr. Adams’ scheme ever goes into effect,” the reporter joked, the vote-counters “will be fit subjects for Flatbush” [i.e., for the Kings County Insane Asylum]. Adams countered by saying, “If a man is an ass or an idiot… there is no system that will prevent his voting wrong, but if given an opportunity, I believe the people will try to vote right.”

Charles also advocated repeatedly for grounding government in local “town halls.” He explored how to federate the local inputs upward to attain legitimate state, national, and even international results.

For some time, starting in 1902, Adams set up (in jest, at first) a physical precursor to a sort of web blog, to share his latest insights with passers-by directly. This figure from the New York Tribune, shows an easel perched on his doorstep facing the sidewalk. Fresh editions of his written-out thoughts were updated periodically, and organized as in a newspaper with the title “The Editor at Work.”

For some time, starting in 1902, Adams set up (in jest, at first) a physical precursor to a sort of web blog, to share his latest insights with passers-by directly. This figure from the New York Tribune, shows an easel perched on his doorstep facing the sidewalk. Fresh editions of his written-out thoughts were updated periodically, and organized as in a newspaper with the title “The Editor at Work.”

More seriously, Adams was, for many years, an intellectual disciple and friend of economic reformer Henry George, who wrote the widely influential book Progress and Poverty (1879).

Adams came to similar economic views earlier, himself, regarding land (including the natural environment): He wrote in the Brooklyn Monthly in 1878: “There is really no reason why land, which is absolutely needed by all, directly and indirectly, and which is the natural gift of God to the human race, should be allowed to become private property, instead of having the rent of it applied for the benefit of the entire people.”

George’s elegantly-argued treatise agreed that, ideally, we should “make land common property.” But since much land is currently privately owned, George offered a pragmatic alternative: tax only people’s land, and not the goods or wealth built on or using the land. The effect would be similar to landowners paying to rent the land they benefit from.

“Single Taxers” became the label for those supporting Henry George’s ideals. Charles Frederic Adams was often at their forefront. Sometimes, it was by supporting George in campaigns for electoral office (1886 and 1897); or speaking at organizations like the Manhattan Single Tax Club, or lobbying for municipal ownership of railways, or even running for election himself (for NYS Supreme Court) in 1906.

From 1910, he traveled extensively for a year, for the Henry George Lecture Association. Groups that Charles Frederic Adams joined or founded or spoke to, about One Taxers, or Electoral reform, or other causes were numerous.

This fitted the man who detested being boxed into static categories. He just as happily visited and spoke to traditional groups, such as Democrats or trade unions. Some listeners found him eccentric, or thought his ideas too impractical. But few ever questioned his obvious intelligence, passion and sincerity. His widow kept his vision alive, joining the Brooklyn Single Tax Club Board, herself, in 1919.

Over his lifetime, Charles Frederic Adams could not single-handedly dismantle political machines; but he exposed thousands of people to his sincerely held vision: People, if given the chance, can vote for qualified representatives, and consider new ways to improve the general welfare — from fairer taxes, to having better supports in retirement or poverty. He invited people to not settle for the currently-accepted approaches, but to always explore better solutions.

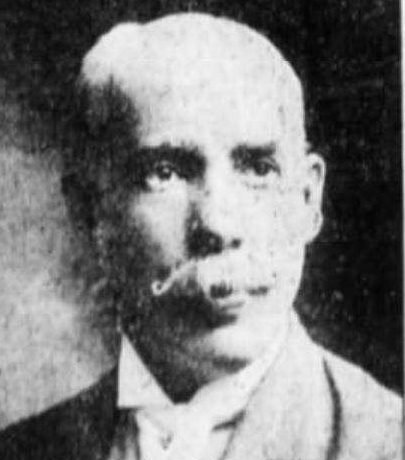

Illustrations, from above: Charles Frederic Adams as a candidate for Supreme Court Nomination for second judiciary district (Brooklyn Eagle, Oct. 9, 1906); 1888 Cleveland-Thurman campaign poster; Sample Ballot for Adams’ 1897 Experiment in Nominations; and an issue of Adams’ ‘The Editor at Home’ on its Easel with Portrait Insert (Composite photo published in New-York Tribune, Oct 5, 1902).

Recent Comments