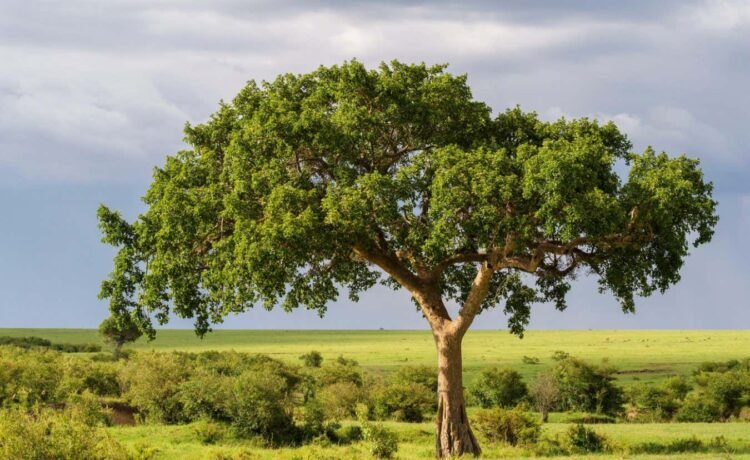

Fig trees may be especially good at removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

Raimund Linke/mauritius images GmbH/Alamy

Some fig trees can convert surprisingly large amounts of carbon dioxide into stone, ensuring that the carbon remains in the soil long after the tree has died. This means that fig trees planted for forestry or their fruit could offer additional climate benefits through this carbon-sequestration process.

All trees take up CO2 from the air, and most of that carbon typically ends up as structural molecules used to build the plant, such as cellulose. Some trees, however, convert CO2 into a crystal compound called calcium oxalate, which bacteria in the tree and the soil can then convert to calcium carbonate, the main component of stones like limestone and chalk.

Carbon in mineral form can stay within soil for much longer than it can in the tree’s organic matter. The trees known to store carbon in this way include the iroko tree (Milicia excelsa), which grows in tropical Africa and is used for timber, but does not produce food.

Now, Mike Rowley at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and his colleagues have found that three species of fig tree native to Samburu County in Kenya can also make calcium carbonate from CO2.

“A large part of the trees becomes calcium carbonate above ground,” says Rowley. “We [also] see entire root structures that have pretty much turned to calcium carbonate in the soil where it shouldn’t be, in high concentrations.”

The team first identified the fig tree species that produce calcium carbonate by squirting weak hydrochloric acid onto the trees and looking for bubbles – a sign of CO2 being released from calcium carbonate. Then, they measured how far away they could detect calcium carbonate in the surrounding soil and analysed samples of the trees to see where in their trunks calcium carbonate was being produced.

“What was really a surprise, and I’m still kind of reeling from, is that the [calcium carbonate] had really gone far deeper into the wood structures than I expected,” says Rowley, who will present the work at the Goldschmidt Conference in Prague, the Czech Republic, this week. “I expected it to be a superficial process in the cracks and weaknesses within the wood structure.”

The researchers will need to do more work to calculate how much carbon the trees are storing, as well as how much water they need and how resilient they are in different climates. But if fig trees can be incorporated into future reforestation projects, then they could be both a food source and carbon sink, says Rowley.

Topics:

Recent Comments