A research-informed guide with definition, benefits, classroom strategies, and a clear comparison to summative assessment.

Formative assessment is not an event at the end of a week but an ongoing process. It is the act of gathering evidence about student understanding while learning is still happening and then acting on it. Black and Wiliam’s review of classroom assessment concluded that when teachers use such evidence to adapt instruction, substantial learning gains are possible across grades and subjects.

“All those activities undertaken by teachers and by their students in assessing themselves that provide information to be used as feedback to modify teaching and learning activities.”

Black & Wiliam, 1998, Assessment in Education, p. 7

Definition

Formative assessment is the process of collecting evidence of student learning during instruction and using it to adjust teaching so students can improve before the learning period ends.

“Formative feedback is information communicated to the learner that is intended to modify his or her thinking or behavior for the purpose of improving learning.”

Shute, 2008, Review of Educational Research, p. 153

Purpose and Benefits

The purpose is improvement rather than judgment. The teacher seeks early evidence of understanding and misconception, then responds while there is still time to help. In Visible Learning, feedback sits among the highest-impact influences on achievement, with an average effect size near 0.70, well above a typical year’s growth.

“The learner has to (a) possess a concept of the standard being aimed for, (b) compare the actual level of performance with the standard, and (c) engage in appropriate action which leads to some closure of the gap.”

Sadler, 1989, Instructional Science, p. 121

Effective use benefits teachers and students. Teachers gain a sharper picture of progress and can adjust pacing, grouping, and emphasis. Students learn where they are in relation to the goal and what action to take next.

Formative vs Summative Assessment

Formative and summative serve different ends. One steers learning in real time. The other certifies what has been learned. They work best together.

| Aspect | Formative Assessment | Summative Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Improve learning while it is happening | Evaluate what has been learned |

| Timing | Ongoing during instruction | End of unit or term |

| Feedback | Immediate, focused on next steps | Usually delayed, focused on final judgment |

| Use of Results | Adjust teaching, reteach, extend learning | Assign grades, certify mastery |

Core Principles

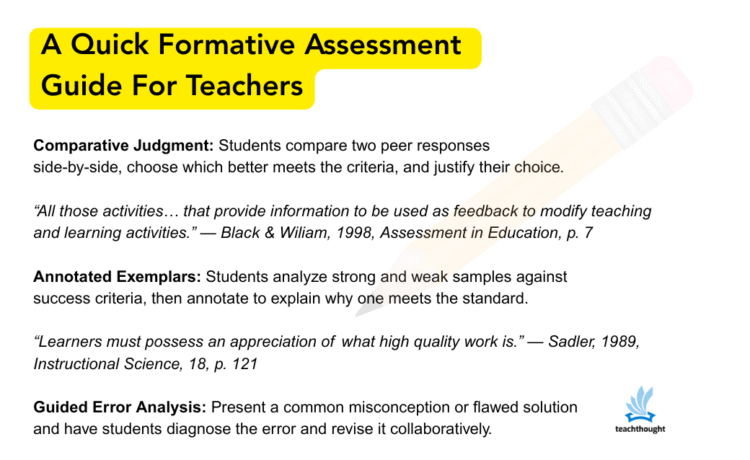

Begin with clarity. Students need to see the target in language they understand and examine what quality work looks like. Elicit evidence regularly through discussion, observation, and analysis of work, not only through tests. Give feedback that names a next step the learner can act on. Involve students directly in judging their own work against criteria and planning what to do next.

“Good feedback practice helps clarify what good performance is, facilitates the development of self-assessment, and delivers high-quality information to students about their learning.”

Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006, Studies in Higher Education, p. 205

Classroom Strategies

Choose a small number of high-value checks that reveal current understanding. A single well-crafted question with think time can show whether the class is ready to move. An exit prompt can sort responses into ready, almost, and not yet, which in turn plans tomorrow. Sampling student work during practice can surface common errors that merit a brief whole-class clarification. As Sadler reminds us:

“If pupils are to become competent assessors of their own work … they need sustained experience in ways of questioning and improving the quality of their work, and supported experience in assessing their work in addition to understanding what count as the standard expected and criteria on which they will be assessed.”

Sadler, 1989, Instructional Science

Responding to Evidence

Plan the response when you plan the check. If many students miss the idea, use a short whole-class reteach. If a few miss it, provide a targeted small-group explanation while others work independently or extend the concept. Build a revision cycle into major tasks so students act on feedback before the learning period ends.

“Feedback functions formatively only if the information fed back to the learner is used by the learner in improving performance.”

Wiliam, 2011, Embedded Formative Assessment, p. 108

Common Pitfalls

Grading *everything* is exhausting. It’s overwhelming to you and overwhelming for students, too. Pick asssessment data tools cafrefully.

Collecting data without acting on it turns checks into busywork, flooding a lesson with many low-yield prompts distracts from the goal.

High-quality formative assessment is purposeful, brief, and tied to immediate instructional decisions.

Pre-teaching Check for Teachers

Is the learning target in student-friendly language they will be able to at least paraphrase?

What’s the most single, most important piece of evidence will I collect today to learn who is ready, who is almost ready, and who is not yet?

Why do you think that’s the most important?

How do you think that evidence might change tomorrow’s plan?

References

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7–74.

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning. Routledge.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189.

- Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment. Solution Tree.

Recent Comments