At present, politicians London and Washington are alert to Beijing’s attempts to exploit Anglo-American technology. They are weary of China stealing trade secrets, copying methodologies, or obtaining sensitive business data, whilst Western companies continue to seek admission to the Chinese market.

At present, politicians London and Washington are alert to Beijing’s attempts to exploit Anglo-American technology. They are weary of China stealing trade secrets, copying methodologies, or obtaining sensitive business data, whilst Western companies continue to seek admission to the Chinese market.

Over time, Britain and America themselves have been involved in acts of intellectual property theft. In fact, the United States accuses China of similar illicit practices that helped its nascent industry leapfrog that of European rivals and come out as an industrial giant. The means used today may be more sophisticated, but the purpose of gaining a competitive edge remains the same.

Fears of Espionage

Platform eleven at London’s Paddington Station hosts a tavern named the Isambard. This public house at one of the city’s main stations celebrates the genius of engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859). Father and son Brunel are notable examples of the contribution European migrants have made to Britain’s technological development.

Educated in England and France, young Brunel was by far the most versatile engineer of the nineteenth century, responsible for the design of tunnels, bridges, railways, and ships. His father, Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849), had fled his native country during the French Revolution, but experienced plenty of adversity in his early career.

Educated in England and France, young Brunel was by far the most versatile engineer of the nineteenth century, responsible for the design of tunnels, bridges, railways, and ships. His father, Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849), had fled his native country during the French Revolution, but experienced plenty of adversity in his early career.

Having accumulated heavy debts in London, he was sent to prison. With no prospect of release, Marc let it be known that he considered accepting an offer of employment by the Tsar of Russia. In August 1821, facing the prospect of losing an able engineer and fearing industrial espionage, the government cleared Marc’s debts in exchange for his continued service. By any government’s standards, it proved to be a wise decision.

In the age of Brunel, British authorities feared that foreign intruders were out to steal the secrets of the nation’s industrial success. Ironically, many prominent tool and instrument makers were immigrants themselves who had traveled from German-speaking states or the Swiss – Italian Como district and settled in British cities to contribute to the industrial miracle of the nineteenth century.

The names of John Weiss, John Henry Dallmeyer, Francis Amadio, Martinelli & Co., Ronchetti Brothers, or Negretti & Zamba deserve a special place in the history of London instrument makers.

One would assume that unease about commercial espionage only became an issue at the time of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. That is not the case. Fears of losing production “secrets” were expressed earlier, leading to legal steps to prevent this from happening.

Danish Intruders

There is a tendency to associate migration with the movement of people from poor countries to more developed ones. The arrival of Flemish and Dutch nationals during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in England proves that this is not the case.

Strangers from the Low Countries were either welcomed as (Protestant) refugees or invited to settle because of their technical skill and commercial competence. Professional craftsmen such as weavers, gardeners, painters, stone masons, and musicians (instrument makers) were encouraged to cross the Channel. English ambassadors in the Low Countries functioned as industrial and artistic “spies.”

As British technology surged forward, industrial (or economic) espionage became a topic that was new to the debate on international relations and migration. The illegal acquisition of trade secrets was a by-product of mechanization.

Industrialists tried to keep hold of their tools, manufacturing processes, and research data to protect their market share against competitors. The government passed an act banning the foreign sale of knitting frames as early as 1696. Other legislation would follow to prohibit the export of machinery and prevent skilled workers from leaving the country.

Industrialists tried to keep hold of their tools, manufacturing processes, and research data to protect their market share against competitors. The government passed an act banning the foreign sale of knitting frames as early as 1696. Other legislation would follow to prohibit the export of machinery and prevent skilled workers from leaving the country.

Despite restrictions, many machine makers and operatives were tempted to emigrate, whilst foreign visitors managed to smuggle drawings of machinery out of the country for replication at home.

In 1777, Thomas Bugge (1740-1815) became Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy at the University of Copenhagen. Keen to modernize the observatory on top of the city’s Round Tower (Rundetaarn, Europe’s oldest functioning observatory), and promote Denmark’s industry, he sent his student Jesper Bidstrup to London in 1787 to learn about the latest technological advances. Bugge recommended Bidstrup to his influential friend Joseph Banks who introduced the young man to leading instrument makers.

These masters ran a “closed shop.” They charged high fees for training apprentices, and their output was protected by the 1790 Tools Acts. Getting access to Jesse Ramsden’s famous dividing engine, a tool employed in making scientific instruments, was open solely to British traders.

With the help of a network of Masonic brethren, Bidstrup set up a workshop at 36 St Martin’s Lane, just off Leicester Square (where Isaac Newton once lived). Around 1793, he published a sale catalogue of “optical, mathematical and philosophical instruments made and sold by J. Bidstrup.” It was a perfect cover.

He spent ten years in London copying models, buying tube glass cutting machines and a dividing engine, before planning his return in 1797. Dismantled machines were loaded on board separate ships destined for Cuxhaven and Copenhagen. Bidstrup did not live to enjoy the fruits of his activities. He died in 1802. His machinery was impounded as state property and handed to other Danish instrument makers.

Den of Piracy

For eighteenth century America to build its economy, it needed skilled workers able to assemble machines acquired overseas (by whatever means). The young United States began as a “pirate nation,” getting hold illicitly of European technology to fuel its Industrial Revolution. Lacking a manufacturing base, America relied on theft.

The nation’s first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton aimed at jump-starting industrialization and advocated a system that would reward those who brought “secrets of extraordinary value” into the country. The acquisition of technology was essential for transforming the United States from an agrarian economy into a manufacturing power. In 1791, he set out his strategy to Congress in the seminal “Report on Manufactures.”

The nation’s first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton aimed at jump-starting industrialization and advocated a system that would reward those who brought “secrets of extraordinary value” into the country. The acquisition of technology was essential for transforming the United States from an agrarian economy into a manufacturing power. In 1791, he set out his strategy to Congress in the seminal “Report on Manufactures.”

Hamilton argued that procuring European machinery was vital to the American economy. With Britain as a prime target, he and his assistant Tench Coxe encouraged state-sponsored theft of trade secrets, blueprints, and industrial tools, as well as recruiting mechanics. They supported individuals who engaged in these actions.

Marylander Thomas Digges was an illicit agent encouraging English and Irish textile workers to emigrate to the United States. George Washington praised him for his efforts to send “artisans and machines of public utility” to America. Federal patents were granted to individuals for technological inventions pirated from abroad. The upstart country was a den of piracy, a rogue nation.

The British government introduced restrictions on the export of technology and limit the migration of innovators or skilled workers. Foreign head-hunters were threatened with a year in prison for every Brit they recruited to work overseas, but the authorities proved unable to stop the flow of skills.

The brain drain had started long before invention of the term. The creative mind is not and will never be state-owned. The most telling case of a British entrepreneurial exodus was that of Samuel Slater (1768-1835), the “Father of the American Industrial Revolution.”

Slater the Traitor

Although cotton was grown in the United States, the country had no domestic textile manufacturing industry. The technology was British and remained closely guarded. In 1733, Lancashire-born John Kay had patented the “flying shuttle,” allowing a single weaver to work at much higher speeds.

Half a century later (1785), Nottinghamshire-born Edmund Cartwright invented the mechanical “power loom,” moving production from homes to factories. Skilled workers and tool makers stood in the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution. They were forbidden to leave the country.

Half a century later (1785), Nottinghamshire-born Edmund Cartwright invented the mechanical “power loom,” moving production from homes to factories. Skilled workers and tool makers stood in the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution. They were forbidden to leave the country.

Samuel Slater was born on June 9, 1768, in Belper, Derbyshire, into a farming family. Aged ten, he began work at a local cotton mill recently opened by Jedediah Strutt, using the water frame pioneered by Richard Arkwright. By the age of twenty-one, he had gained a thorough knowledge of the cotton spinning process.

He embodied skills the British government wanted to hold onto, but Slater learned of American interest in developing similar machines and was tempted by the generous financial rewards on offer. He was also aware of the legal ban on exporting designs and blueprints. He memorized all vital details of Arkwright’s operation, before leaving for the city of New York in 1789.

Having secured the backing of Rhode Island merchant Moses Brown, he constructed America’s first water-powered cotton spinning mill in 1790. Three years later, Slater and Brown opened their first textile factory at Pawtucket, Providence County.

Domestic textile manufacture grew rapidly, becoming America’s most important pre-Civil War industry. Cotton production became a central part of the nation’s early economy. It marked the beginning of a manufacturing boom for New England.

Domestic textile manufacture grew rapidly, becoming America’s most important pre-Civil War industry. Cotton production became a central part of the nation’s early economy. It marked the beginning of a manufacturing boom for New England.

In the South, cotton became the chief crop (both for export and domestic use); the increase in production was stunning: from about 3,000 bales in 1793 to over 175,000 bales by 1800. Vast demand for cotton shaped the region’s harsh slave labor economy.

Slater eventually owned thirteen spinning mills, developing settlements of working families around them (child labor at the mills was a standard practice). One of these towns was Slatersville, Rhode Island. In Derbyshire people named him “Slater the Traitor,” as textile workers considered his move a betrayal that threatened their mills and livelihoods.

Slater’s extraordinary power of recollection was equaled by the Massachusetts industrialist Francis Cabot Lowell who, in 1812, toured England and Scotland. Visiting various textile mills, he closely observed their design and operations.

On his return journey, Lowell’s ship was searched by British customs officers on suspicion that he was in possession of industrial designs. They found nothing as Lowell had memorized the blueprints of Cartwright’s power loom. He built the first integrated textile mill in Massachusetts.

Intelligence Services

During the First World War, industrial espionage became state-sponsored economic warfare, disrupting supply chains, gathering intelligence on weaponry and shipbuilding, and sabotaging munitions production. As the battlefield had become mechanized, both the Allied and Central Powers faced the challenge of destroying the enemy’s manufacturing capacity.

The war compelled the creation of professional intelligence services. The post-war focus shifted towards stealing data related to aeronautics, electronics, or chemicals. Cold War espionage became a systematic effort to narrow (nuclear) research gaps, involving attempts by the Soviet Union and its allies to get hold of American atomic, military, and industrial secrets.

The war compelled the creation of professional intelligence services. The post-war focus shifted towards stealing data related to aeronautics, electronics, or chemicals. Cold War espionage became a systematic effort to narrow (nuclear) research gaps, involving attempts by the Soviet Union and its allies to get hold of American atomic, military, and industrial secrets.

Japan’s rise as a global powerhouse started during the Meiji Restoration Era and was driven by technology acquisition, either by legal means or through espionage. The aim was to catch up with the West. The government sent students and officials to Europe and America to infiltrate universities and gather data.

The country’s rapid ascent (an “Economic Miracle”) during the 1970s and 1980s was fueled by espionage, particularly targeting Silicon Valley.

Industries closed the gap by obtaining (stealing) trade secrets in sectors such as semi-conductors and computing (in the 1982 “Japanscam,” employees from Hitachi and Mitsubishi were caught buying stolen IBM secrets). As Japanese companies evolved from copyists to innovators, they were forced to find ways of protecting their own intellectual property.

Today, China is the primary actor in the theater of espionage. The “China Threat” (in terms of the FBI) consists of spying efforts pursued by the Communist government. The country is competing with the United States to become the world’s superpower by supporting predatory business deals, theft of intellectual property, and aggressive cyber intrusions.

Economic and national security can no longer be separated. Some American analysts label China a “rogue state.” The irony is that the practice was justified in black and white by Alexander Hamilton in his 1791 report to Congress.

Read more about New York State’s Industrial History.

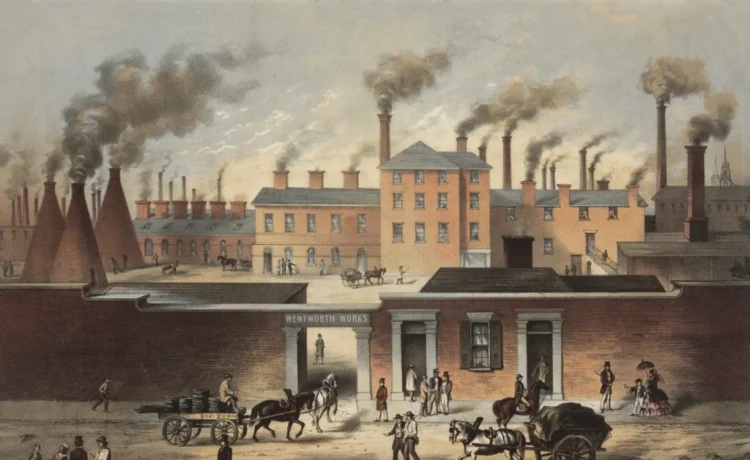

Illustrations, from above: The well-guarded Wentworth Works steel factory in Sheffield, England, 1860; Portrait of Marc Isambard Brunel by James Northcote, 1813; A trade card of instrument maker J.M. Hyde, Bristol, 1841-55; An 1809 edition of Hamilton’s ‘Report on Manufactures,’ 1791; James Sullivan Lincoln’s Portrait of Samuel Slater, date unknown (Brown University, Providence); Jedediah Strutt’s textile mill at Belper, Derbyshire diagram showing the construction, waterwheel and line shafts; and the Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, around 1897.

Recent Comments