Author and public servant James Kirke Paulding was born on August 22, 1779, in Great Nine Partners along the Hudson River in Dutchess County, NY, at the height of the American Revolution. His family was forced to take refuge from British invaders in Westchester County, returning after peace was declared.

Author and public servant James Kirke Paulding was born on August 22, 1779, in Great Nine Partners along the Hudson River in Dutchess County, NY, at the height of the American Revolution. His family was forced to take refuge from British invaders in Westchester County, returning after peace was declared.

James’s father William was an active patriot and from him he inherited strong anti-English sentiments. He would become one of the first distinctively American writers who vigorously argued the case against intellectual or artistic servitude towards Britain.

Salmagundi & Gotham

In 1798, James moved to the city of New York and lived with his elder brother William Paulding who had secured a job for him in local government. A prominent attorney, William was elected to the House of Representatives in 1811. He would eventually serve as the 56th and 58th Mayor of New York

(terms: 1824-25 and 1827-29).

James thrived in this urban environment. When his sister married William Irving whose house was second home to many young men engaged in literary pursuits, he became acquainted with Washington Irving. A friendship sprang up between them which continued unbroken to the last.

Both were aspiring authors and they soon joined up with other young writers (including James Fenimore Cooper and William Cullen Bryant), thereby creating one of Manhattan’s first literary salons, unofficially called the “Knickerbocker Group.”

Members often assembled at Dyde’s Hotel, next door to the Park Theatre on Park Row. During an encounter at William Irving’s place, Paulding proposed a literary project to his friend to establish a periodical that would differ from serious news publications of the day, merely for their own amusement and that of their readers.

In January, 1807, the first number of Salmagundi; or The Whim-whams and Opinions of Launcelot Langstaff Esq. & Others was issued. Commonly referred to as Salmagundi, it was a joint venture apart from a number of contributions submitted by William Irving.

In January, 1807, the first number of Salmagundi; or The Whim-whams and Opinions of Launcelot Langstaff Esq. & Others was issued. Commonly referred to as Salmagundi, it was a joint venture apart from a number of contributions submitted by William Irving.

In their sketches, both authors took delight in satirizing the social follies of the day and poking fun at politics in order to “instruct the young, reform the old, correct the town, and castigate the age.” In the issue of November 11, 1807, Irving first attached the nickname “Gotham” to New York City (based

on famous tales of alleged “fools” living in the village of Gotham, Nottinghamshire, England).

The collaborators produced twenty issues at irregular intervals between January 24, 1807, and January 15, 1808. Publication of the periodical was suddenly discontinued, following a disagreement with publisher David Longworth over the remuneration of its authors. Nothing of the kind had ever

appeared from an American press. Its success determined the subsequent literary careers of both authors.

The magazine’s title was inspired by food. Salmagundi is a seventeenth century English cold dish or salad, comprising ingredients such as cooked meats, seafood, vegetables and fruits with a dressing of oil, vinegar and spices arranged in an elaborate manner. Something of a gastronomical mess. The word was derived from the French in the meaning of a “hodgepodge” of widely disparate edible parts.

John Bull & Decadent France

James Kirke Paulding became a prolific author, but The Diverting History of John Bull and Brother Jonathan, published as early as 1812 and passing through numerous editions, remains in the judgment of many readers and critics one of his better works.

Thanks to John Arbuthnot’s creation of his political satire The History of John Bull, the latter had emerged as the national personification of England. The author provided him with a sister named Peg (Scotland) and adversaries in the figures of Nicholas Frog (Netherlands) and Louis Baboon (the French House of Bourbon). Peg continued in pictorial art beyond the eighteenth century, but the other figures associated with the original tableau dropped away.

In subsequent representations, John Bull is portrayed as a stout man with a Union Jack waistcoat. Wearing a low topper on his head and accompanied by a bulldog, he is a man of native country stock with a great deal of common sense. He is not a figure of authority, but rather a yeoman who likes his beef, beer and domestic peace.

John Bull’s diet is an expression of identity. By eating quantities of beef, he showed contempt for the foppish kickshaws served on the tables of the aristocracy (the word “kickshaw” is a corruption of the French “quelque chose,” meaning recipes in which eggs and cream were used). Beef was considered

fundamentally English, reflecting an “honest” Protestant character in contrast to the ragouts, fricassées, patés and jellies of the French “charcutier.”

The implication is clear: native means wholesome, foreign indicates weakness. Traditional home food is set against foreign fashion, simplicity against affectation – Old England against decadent Catholic France.

Ever since the nation state had become a central organizing factor in social life, food chauvinism or gastro-nationalism has given rise to idioms of eating, stomach and belly in political discourse.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries an English person identified himself in opposition to his French counterpart by an addiction to beef. English nationalism was driven by images of the bulldog and the master butcher. Beef was both cultural symbol and bearer of national identity.

Brother Jonathan & Decadent England

Brother Jonathan was an early fictional representation of the entire United States. Initially used as a term of derision by Loyalists to describe the Patriots of the late 1770s and early 1780s, it soon became a badge of honor. In editorial cartoons and patriotic posters, Brother Jonathan was depicted as a “typical” American revolutionary, with a tri-cornered hat and long military jacket. Cartoon depictions of Jonathan started to appear during the War of 1812.

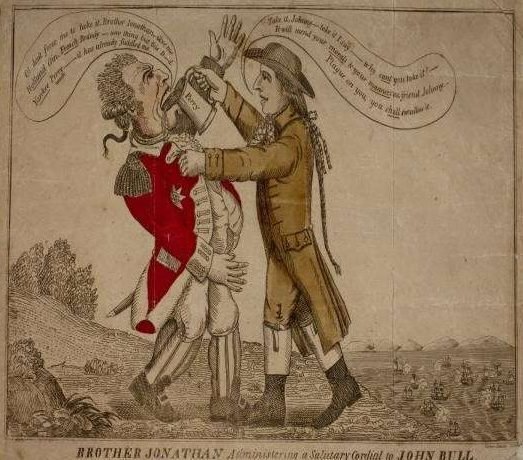

New Haven artist Amos Doolittle was an early American engraver of significance. As a young man in 1775, he had joined then Captain Benedict Arnold of the Continental Army and his experiences resulted in four copperplate engravings of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first published images of the armed conflict. In 1813 he produced under the name of “Yankee Doodle” a hand-colored political cartoon entitled “Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutary Cordial to John Bull.”

![Yankee Doodle [= Amos Doolittle], “Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutary Cordial to John Bull”, 1813.](https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Yankee-Doodle-Amos-Doolittle-Brother-Jonathan-Administering-a-Salutary-Cordial-to-John-Bull-1813-e1733253484742-300x275.jpg)

![Yankee Doodle [= Amos Doolittle], “Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutary Cordial to John Bull”, 1813.](https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Yankee-Doodle-Amos-Doolittle-Brother-Jonathan-Administering-a-Salutary-Cordial-to-John-Bull-1813-e1733253484742-300x275.jpg) The image shows Brother Jonathan pouring a drink of “perry” (a fermented pear juice that would upset the stomach of any drinker) down the throat of John Bull. Perry is also a reference to Naval Commander Oliver Hazard Perry whose victory on Lake Erie prevented the British from gaining control of the Great Lakes.

The image shows Brother Jonathan pouring a drink of “perry” (a fermented pear juice that would upset the stomach of any drinker) down the throat of John Bull. Perry is also a reference to Naval Commander Oliver Hazard Perry whose victory on Lake Erie prevented the British from gaining control of the Great Lakes.

Brother Jonathan is pictured in late eighteenth-century clothes with top-boots, symbolizing the America nation as modest and honest and morally superior to John Bull who appears pompous in a crimson uniform bedecked with epaulets and medals.

This contrast is reflected in the transcript of the text: John Bull: “O! don’t force me to take it, Brother Jonathan – Give me Holland Gin, French Brandy – anything but this D-d Yankee Perry – it has already fuddled me.” Brother Jonathan: “Take it, Johnny – take it I say – why can’t you take it? – It will mend

your morals & your manners too, friend Johnny. – Plague on you, you shall swallow it.”

In the accompanying advertisement for the cartoon, Doolittle wrote that his motivation was “to inspire our countrymen with confidence in themselves, and eradicate any terrors they may feel as respects the enemy they have to combat.”

The term Uncle Sam appeared around the same time. His origins are disputed, but the name usually is associated with Sam Wilson of Troy, a businessman who supplied the Army during the War of 1812. His barrels were stamped “U.S.” for the government, leading him to nickname.

Uncle Sam’s appearance evolved from that of Brother Jonathan. The two characters were used interchangeably from the 1830s through the 1860s. As had been the case with John Bull’s presence, cartoonists of Punch magazine helped develop the figure of Uncle Sam, showing him as a lean, whiskered man wearing a top hat and striped pants.

Thomas Nast gave shape to the image with his cartoons beginning in the 1870s. When James Montgomery Flagg depicted him on the famous World War I recruiting poster in 1917, Uncle Sam had become an icon. In 1950, he was officially adopted as the national symbol of the United States.

Political Career

The literary and journalistic “Paper War” in the Anglo-American relationship climaxed with the appearance of Inchiquin, the Jesuit’s Letters published in 1810 in New York. Credited to “some unknown foreigner,” these letters purported to be the private correspondence of an Irish priest residing in the United States.

A review of the pamphlet in the London Quarterly Review for January 1814 sparked an angry response in America where the piece was seen as a “nefarious tissue of calumnies on the American character.” The intent of the journal’s editors was to direct focus on the moral condition of the United States and the way in which Britain would “handle” the New Republic, both militarily and diplomatically.

In response to the article, Paulding published his pamphlet “The United States and England” in 1814. His stated goal was to build national confidence. Looking backward over time, he points at the English presence in America as a chronicle of misdeeds. The history of “our intercourse with England exhibits a series of arrogant pretension on her part, and patient, if not silent, endurance on ours.”

In response to the article, Paulding published his pamphlet “The United States and England” in 1814. His stated goal was to build national confidence. Looking backward over time, he points at the English presence in America as a chronicle of misdeeds. The history of “our intercourse with England exhibits a series of arrogant pretension on her part, and patient, if not silent, endurance on ours.”

Throughout the pamphlet, Paulding portrays England as a “degenerate, despotic kingdom, burdened by parasitical aristocracy and jealous of America’s success.” In comparison to the United States, England was more cluttered with dissident denominations, alcoholism was more rampant, blood sports were more cruel and elections less honest. America therefore needed to free itself from any idea of inferiority or call for subservience.

This strongly Anglophobic pamphlet attracted the attention of President James Madison and paved the way for the author’s subsequent political career. Soon after the appearance of this work he was made Secretary to the first Board of Navy Commissioners. President Martin Van Buren appointed him US

Secretary of the Navy, a position he held from 1838 to 1841.

Paulding’s political career had been driven forward by his role as an anti-English angry young man.

Illustrations, from above: James Kirke Paulding; Title page for the periodical Salmagundi; Yankee Doodle [Amos Doolittle], “Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutary Cordial to John Bull”, 1813; and Anonymous [James Kirke Pauling] “The United States and England,” 1815.

Recent Comments