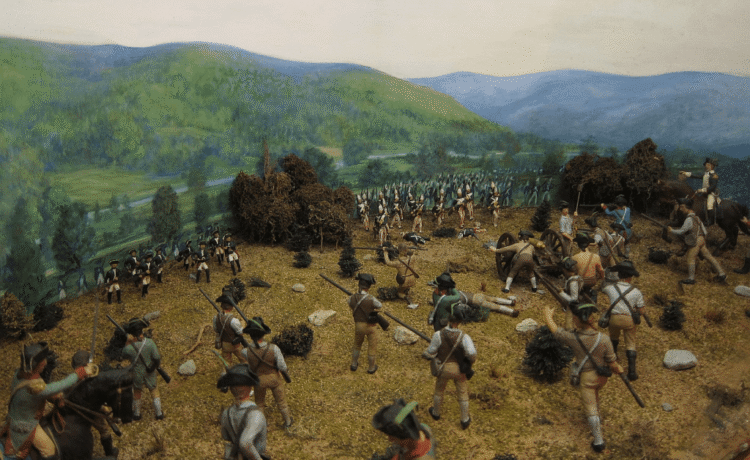

The summer of 1777 found the British Army well into the campaign season of the third year of the American Revolution. General John Burgoyne, at the head of over 8,000 troops, with accompanying artillery, baggage train, and a supply of boats, had been driving southward for three months, capturing major and minor forts and sweeping aside the Rebel navy and armies which constantly harassed his advance.

The summer of 1777 found the British Army well into the campaign season of the third year of the American Revolution. General John Burgoyne, at the head of over 8,000 troops, with accompanying artillery, baggage train, and a supply of boats, had been driving southward for three months, capturing major and minor forts and sweeping aside the Rebel navy and armies which constantly harassed his advance.

His campaign was part of a broad British strategy designed to divide the Colonies in half with one massive, three-pronged attack.

Burgoyne, with the main force, was to drive south through the Champlain Valley, across the highlands beside Lake George via the Wood Creek corridor, and into the upper Hudson Valley.

Colonel Barry St. Leger was to sweep eastward along the Mohawk Valley out of Oswego on Lake Ontario, and General Sir William Howe was to insure the success of the expedition with a naval drive north out of the city of New York, a British stronghold, to wrest the lower Hudson Valley from American control.

The goal of these spearheads was the city of Albany, where all three forces must meet before the winter of 1777 ended the campaign season.

By early August, Burgoyne found his army slowed by lack of provisions and an elongated supply line that suffered from lack of wagons and carts. In addition, the effectiveness of several key units was undermined by the lack of horses, thus weakening as well as retarding his offensive.

James Hadden, who was with Burgoyne’s Army, noted that “because the Regiment of Dragoons were to be mounted, surely it was no reason they should be detached with swords weighing at least 10 or 12 pounds, particularly as Dragoons cannot be expected to march or maneuver well on foot and be expert at treeing or bush fighting.”

In order to relieve this potentially threatening situation, Burgoyne dispatched a small expeditionary force eastward into New England via the supposed Loyalist strongholds of Eastern New York, an area commonly called “Dutch Hosack.”

Meanwhile, in New England, militia and supplies were being gathered at Bennington to be sent to oppose the advance of Burgoyne down the Hudson Valley.

By mid-August about 2,800 Massachusetts and New Hampshire militiamen under General John Stark, and local Patriots, Green Mountain Boys and Vermonters under Seth Warner, had gathered.

This store of provisions, which included horses, cattle, and wagons, attracted Burgoyne’s attention, and his expeditionary force of about 1,400 men (British Regulars, Canadian and Loyalist volunteers, Hessians, and Iroquois warriors) under Lieut. Col. Friedrich Baum was directed toward it.

Baum had had little battlefield command experience, spoke only German, and made his headquarters many miles away at Cambridge, in Washington County, NY. Stark however, had served with Robert Rogers’ Rangers, including at the taking of Ticonderoga, had distinguished himself at Bunker Hill, Trenton, and Princeton, and led from the field of battle.

In mid-August these two relatively minor forces collided, somewhat accidentally, in the tiny valley of the Walloomsac River, in the extreme northeastern corner of Rensselaer County, New York.

In mid-August these two relatively minor forces collided, somewhat accidentally, in the tiny valley of the Walloomsac River, in the extreme northeastern corner of Rensselaer County, New York.

That confrontation, which lasted less than 48 hours, is believed by many to have been the death knell of the Burgoyne invasion. Baum was killed in the battle.

The failure of Baum’s expedition, coupled with the loss of support from Howe and St. Leger, directly contributed to the defeat of the main British force at Saratoga a few weeks later.

Most historians believe the Battle of Saratoga turned the tide of the Revolution and was one of the most significant battles in the history of the world.

The degree to which the Battle of Bennington was seen as a mortal blow is reflected by British military historian John Fortescue who concluded that “A stronger man [than Burgoyne] might indeed have retreated, whatever his instructions, after the reverse at Bennington.”

It is also reported that “When Washington heard of Bennington, he regarded it as deciding the fate of Burgoyne and dismissed from his mind all further anxiety about this invasion.”

It is generally believed that the defeat at Bennington delayed Burgoyne’s readiness for battle long enough for the American army to convene sufficient numbers at Stillwater to oppose him.

Had he gathered the support expected from Baum’s expedition and been able to engage the American forces at an earlier date, when they were more vulnerable, Burgoyne may have yet been able to reach Albany on his own, particularly as the British had finally left New York lo begin a diversion up the Hudson River by mid-October.

Although one of the more decisive engagements of the American Revolution, the Battle of Bennington is one of the most poorly documented actions of the War. There are few primary sources on which to draw for clarification, and many of the secondary sources are either ambiguous or contradictory.

A good deal of the reason for this rests with the paramilitary and semi-official nature of the American forces, which were less equipped to keep such records, and felt less obliged, politically, to do so.

You can read about details of the Battle of Bennington in War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Pattern on the Bennington Battlefield (New York State Museum Bulletin No. 473, 1989), compiled by Philip Lord Jr., from which this essay was extracted.

Illustrations, from above: Map of American and British troop movements during Burgoyne’s American Revolution Campaign of 1777 (NPS); and diorama of the battle at the Bennington Battle Monument, Seth Warner leads Green Mountain Boys troops on the right from atop his black horse.

Recent Comments