Born in Brooklyn in 1810 in a family of Irish immigrants, John McCloskey became the first American-born Archbishop of New York. When he died in October 1885 after two decades of leadership, the Catholic Church had seen major changes in its place in society. He oversaw the construction of eighty-seven new churches, including the first parish for Black Catholics, and doubled the number of Catholic schools. The Roman Church had gained a voice in society.

Born in Brooklyn in 1810 in a family of Irish immigrants, John McCloskey became the first American-born Archbishop of New York. When he died in October 1885 after two decades of leadership, the Catholic Church had seen major changes in its place in society. He oversaw the construction of eighty-seven new churches, including the first parish for Black Catholics, and doubled the number of Catholic schools. The Roman Church had gained a voice in society.

As a consequence, a gradual shift took place in traditional Protestant hostilities towards Catholicism – and that included New England. A similar re-positioning had happened in northern-European nations

where the Reformation was put in reverse. The number of converts rose dramatically. It reignited a passion for the cultural heritage of Italy.

Appeal of Catholicism

During the early decades of the nineteenth century, the Catholicism in Britain and America was a marginal religion. The populations of both nations were emphatically Protestant and ill-disposed towards “popery.”

The Roman Church was condemned for repressing freedom of thought and the few Catholic intellectuals writing in English faced formidable obstacles in their quest for a hearing.

That climate changed from the mid-nineteenth century onward when a succession of English-speaking intellectuals converted to Catholicism, among them John Henry Newman, G. K. Chesterton, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh and others. These converts usually came from the Anglican or Episcopal Church which remained close to Catholicism, being sacramental, ritualistic and hierarchical.

Converting nevertheless was a major step. More often than not, it prompted accusations of disloyalty.

Converting nevertheless was a major step. More often than not, it prompted accusations of disloyalty.

In 1848, poet Christina Rossetti refused an offer of marriage from James Collinson, a young talented artist of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, because he had converted to the Roman Church. Collinson’s parents disowned him and he was reduced to begging from friends. There were other problems.

Within the Catholic Church converts were treated with some suspicion. Reluctant to accept clerical censorship, they were accused of an intellectual “adventurism” that would undermine orthodoxy rather than fortify it. English and American converts tended to stay away from strictly theological questions altogether and chose to work in the “safer” realms of literature and history.

During the 1890s, a number of English writers converted to Roman Catholicism: poets John Gray, Lionel Johnson and Ernest Dowson joined the Church in 1890/1, while Oscar Wilde flirted with the Catholic faith during his years at Oxford (he received the last sacraments on his deathbed in 1900). These writers all inherited Walter Pater’s taste for the “esthetic” splendors of religious rites.

The revival of Catholic art and literature was more than just a cultural phenomenon and its socio-political impact of this development has been described as a “reactionary revolution.” Religion, politics and literature became entangled in combative polemics.

The Year 1885

In 1885 William Gordon-Gorman compiled a directory entitled Converts to Rome during the XIXth Century in which he listed about “Four Thousand Protestants Who Have Recently Become Roman Catholics” (according to the book’s subtitle). The compiler grouped converts by class, university, profession and geography.

Oxford University saw numerous conversions amongst its scholars, thirteen at Magdalen College and seventeen at Balliol. The directory aimed at highlighting the “startling” advancement of Roman Catholicism in spite of the spirit of the age which was a general “anti-popery.”

Oxford University saw numerous conversions amongst its scholars, thirteen at Magdalen College and seventeen at Balliol. The directory aimed at highlighting the “startling” advancement of Roman Catholicism in spite of the spirit of the age which was a general “anti-popery.”

Catholicism had come under pressure after the Reformation and was thought to fade away with the “clearing” of civilization brought about by the Enlightenment and French Revolution. Rapid developments in science and technology both in Britain and America left no room for superstition and oppression. The compiler of the list proved that the Catholic Church did not suffer or die. Instead, it came roaring back.

Most converts were men, but women were also attracted to Rome. They tended to be well-educated, wealthy and independent. A descendant of New England Puritans, Eliza Allen Starr spent her early adulthood in Boston and Philadelphia where she made many social connections, among them Archbishop Peter Richard Kenrick, an Irish immigrant who influenced her religious thinking.

Having devoted her life to the study and interpretation of Christian painting as well as teaching art at Saint Mary’s Academy near Notre Dame, Indiana, she was received into the Catholic Church in 1854

at Boston’s Holy Cross Cathedral. In 1885, she was the first woman to receive a “Laetare Medal,” the most prestigious award given to American Catholics.

Paradise of Exiles

Italy became a magnet for converts. Anticipating an exemplary Catholic life, they were confronted with a more ambiguous reality. Political upheavals, encounters with cynical Curial officials, obstinate bureaucrats, fraudulent innkeepers, not to mention the continuous battle with bedbugs, offset their admiration for the beauties of Assisi, Venice, Florence or Rome.

There were other than religious reasons for making the “pilgrimage” to Italy. Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairemont were wanderers, living in various Italian cities.

Eventually they set up home in Pisa, where Lord Byron joined them in 1821. They were in thrall to the Renaissance ideals of beauty in art and literature and believed that this Catholic country offered greater tolerance and freedom than their Protestant homeland. They and many other “castaways” engaged with the heritage and literature of the country that Shelley called a “paradise of exiles.”

Anne Hampton Brewster was one of America’s first female foreign correspondents, publishing primarily in Philadelphia, New York and Boston newspapers. She was considered a “social outlaw” as she defied familial and social conventions by supporting herself financially as a writer. Seeking independence, she converted to Catholicism. Living in Rome, she hosted a salon where she entertained writers and musicians.

Anne Hampton Brewster was one of America’s first female foreign correspondents, publishing primarily in Philadelphia, New York and Boston newspapers. She was considered a “social outlaw” as she defied familial and social conventions by supporting herself financially as a writer. Seeking independence, she converted to Catholicism. Living in Rome, she hosted a salon where she entertained writers and musicians.

Boston-born Charlotte Cushman was a Shakespearian actress who found fame after her debut in 1836, performing as Lady Macbeth. She has been named the first American-born star of the stage (performing in both male and female roles). Anne described the relationship between herself and Charlotte starting in the early 1840s as an “intimate friendship.”

Her older brother Benjamin H. Brewster (who would later serve as US Attorney General) strongly objected to the bond and under the yoke of convention the two separated, leaving Anne – who came to regret the split for the rest of her days – “out at sea without rudder or compass” according to her journal notes.

Cushman sailed for England in 1844 and her performances in London (and later Dublin) were a triumph. In the capital she met Matilda “Max” Hays, an advocator for women’s rights and co-founder of the English Woman’s Journal. They became a couple. After Charlotte’s retirement, the pair settled in Rome where they openly lived together in a community of expatriate lesbian artists and sculptors.

At the time, a “Boston marriage” was a euphemistic phrase for a lesbian relationship since the city had become identified with intellectually-minded women who chose female company rather than enter into a conventional marriage.

Rose Cleveland was once described as “a woman of unusual gifts, of large and varied information, of vigorous views and strong convictions.” Born in 1846 at Fayetteville, near Syracuse in Onondaga County, NY, Rose Cleveland was the youngest of nine children of a Presbyterian minister.

Her father Richard died when she was just seven and Rose eventually became a teacher in order to support her widowed mother. When her elder bachelor brother Grover Cleveland was elected the 22nd President of the United States in 1885, Rose became First Lady.

She attracted much attention in the press not only for her “revealing” dress style, but also for being a “blue-stocking” with academic and political interests. During her fifteen months spell as First Lady, she published two studies and a novel entitled The Long Run (1886).

On June 2, 1886, President Grover Cleveland married Frances Folsom in the White House’s Blue Room, relieving Rose from a burdensome task. She left Washington in the same manner as she had arrived, somewhat of an enigma with little care for conventions of etiquette or social niceties. She returned to education, becoming the Head of Lafayette’s Collegiate Institute.

As first lady, she hosted traditional receptions and dinners at the White House while also pursuing her own academic interests. For example, although Miss Cleveland was only first lady for fifteen months, she found time to author two books: George Eliot’s Poetry and Other Studies (1885) and You and I: Moral, Intellectual and Social Culture (1886).

Despite Rose Cleveland’s preference for intellectual pursuits over social gatherings, her receptions were well-attended and she was well-liked. In the winter of 1889, Rose crossed paths in Florida with a wealthy young widow named Evangeline Simpson.

Despite Rose Cleveland’s preference for intellectual pursuits over social gatherings, her receptions were well-attended and she was well-liked. In the winter of 1889, Rose crossed paths in Florida with a wealthy young widow named Evangeline Simpson.

It led to a passionate affair that continued until 1896, when Evangeline suddenly married Episcopal Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple, who was nearly five decades older than her. Although the two women continued to exchange letters, the notes lost their tone of intimacy. When Whipple died in 1901, the way was cleared for the two to come together again.

In 1910, they traveled to Italy to take care of Evangeline’s sick brother. Both found there what they had been craving: the freedom to love and maintain a relationship without the moralistic meddling of

outsiders. Upon the patient’s death in 1912, the coupled decided to stay and settle down as “true partners” in Bagni di Lucca.

English-American Cemetery

A quiet town surrounded by chestnut forests in the Apennine Mountains of Tuscany where the Lima stream joins the Serchio River, Bagni de Lucca was praised for its mild climate and thermal springs which attracted visitors (including a long list of poets, artists and composers) from all over Europe. During French occupation during the early 1800s, it had been the summer residence of the court of Napoleon and his sister Elisa Bonaparte.

Colonel Henry Stisted of the 1st Regiment of Dragoons had fought at the Battle of Waterloo under command of Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. Having retired in 1821, he and his Dublin-born wife Elizabeth Clotilda settled in Bagni de Lucca. A woman of culture, Elizabeth hosted in their “Villa Broderick” many noted visitors, including Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett and Walter Scott. Around them, a small English-speaking community sprang up.

Colonel Henry Stisted of the 1st Regiment of Dragoons had fought at the Battle of Waterloo under command of Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. Having retired in 1821, he and his Dublin-born wife Elizabeth Clotilda settled in Bagni de Lucca. A woman of culture, Elizabeth hosted in their “Villa Broderick” many noted visitors, including Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett and Walter Scott. Around them, a small English-speaking community sprang up.

Once settled, its members expressed a wish for their own place of worship and a cemetery. Having held meetings in the hall of Hotel Pellicano since 1829, they did not obtain building permission until 1840 and on one condition: the building should not be identified as an Anglican Church in the midst of Catholic surroundings.

An agreement was reached and Giuseppe Pardini, chief architect for the city of Lucca, designed a neo-Gothic “Palace of the English Nation.” Funding for construction was organized by Elizabeth Clotilda who, for this purpose solely, penned Letters from the Bye-ways of Italy (published in London by John Murray in 1845).

Spanish Flu

Rose and Evangeline shared a house in Bagni de Lucca with Nelly Erichsen, an English artist and illustrator for books in Dent’s “The Story of…” [Italian City] series which were popular at the start of the twentieth century when, for most people, it was the only way of learning about Italy. The three were much involved in local philanthropic and civic work.

On October 24, 1917, the Central Powers launched a massive offensive at Italy’s north-eastern border. The resulting Battle of Caporetto has been described as the greatest defeat in Italian military history.

Countless refugees gathered in Bagni di Lucca and the three women supported the Red Cross in setting up of a field hospital and orphanage to care for the influx. Those who had fled the onslaught, brought the pandemic of “La Spagnuola” (Spanish flu) with them.

Lacking protective clothing and effective medication, Nelly Erichsen contracted the flu first and died days after World War I ended. Rose who had nursed her, passed away soon after. They were buried at

the “Palace” cemetery. Evangeline survived the pandemic and continued serve the community. She was made an honorary citizen of the town in 1918 and a road was named after her. In 1928, she published A Famous Corner of Tuscany, a history of her beloved Lucca region.

Although she died in London in 1930, Evangeline was buried next to Rose Cleveland in Bagni di Lucca. The resting places of the women are marked by identical monuments. Each of the tombs bears a small sculpted flower linking the three together.

Rose and Evangeline were both born and raised in Massachusetts and the story of their lives is one of shared bravery. Resisting conventional values, they were “misfits” who escaped the suffocating social control of their New England environment, finding freedom to live and love in Catholic Tuscany. It remains one of the (understated) ironies of early-modern history.

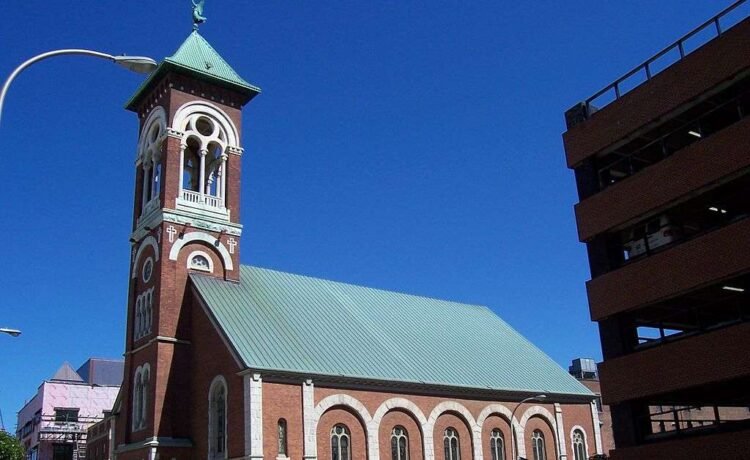

Illustrations, from above: St. Mary’s Church in Albany, John McCloskey’s first episcopal see; a portrait of Christina Rossetti by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1866; frontispiece to a modern edition of Catholic Converts to Rome; albumen photograph of Anne Hampton Brewster, ca. 1874; Rose Elisabeth Cleveland, First Lady; Evangeline Simpson Whipple, ca. 1896; and the Anglican Church at Bagni de Lucca.

Recent Comments