Attached to the bric

k wall of a restaurant/brewery called Death Avenue at 10th Avenue, almost hidden out of sight, a curious little plaque features a period photograph (ca. 1898) of steam locomotive running at street level surrounded by tenements, horses, pedestrians and children.

k wall of a restaurant/brewery called Death Avenue at 10th Avenue, almost hidden out of sight, a curious little plaque features a period photograph (ca. 1898) of steam locomotive running at street level surrounded by tenements, horses, pedestrians and children.

It commemorates hundreds of people who had lost their lives to the train. One of the victims was Seth Low Hascamp, a young boy (most likely) born into a family of German immigrants.* His death would help transform the area and its safety, a changeover that was recorded by a local Union Square artist.

Urban Cowboys

In 1846, the City of New York made what turned about to be a poor decision to authorize the construction of railroad tracks without barriers down the middle of 10th and 11th Avenues.

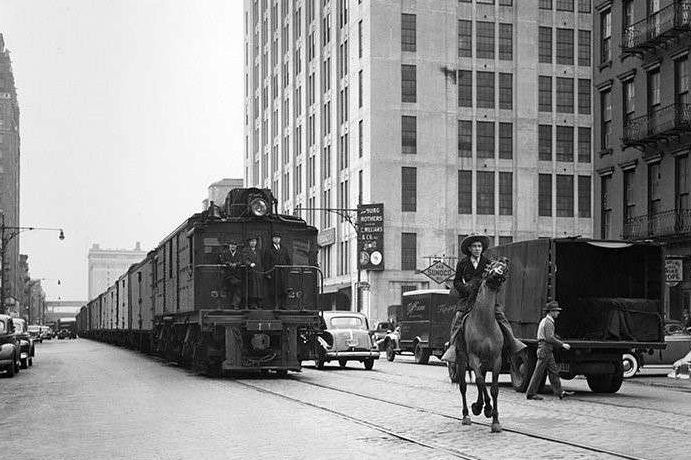

For nearly a century, giant steam locomotives operated by the New York Central Railroad pulled freight cars, sometimes several blocks long, through Manhattan’s congested streets, shipping commodities such as coal, dairy products and beef. Running along meat warehouses and grocery outlets, the railroad was responsible for much of the city’s food supplies.

The locomotives were equipped with hand brakes operated by a single person from the top of the car, but stopping the train quickly proved impossible. When mixed with an ever-growing crush of hansom cabs, motor cars and trucks, accidents happened regularly.

Hundreds of people were either killed or mutilated, many of them pedestrians and schoolchildren. For its large share of fatalities, 10th and 11th Avenues earned the moniker “Death Avenue.” The phrase was coined in 1892 by the New York World lamenting that so many lives had been sacrificed to a menacing “monster.”

Hundreds of people were either killed or mutilated, many of them pedestrians and schoolchildren. For its large share of fatalities, 10th and 11th Avenues earned the moniker “Death Avenue.” The phrase was coined in 1892 by the New York World lamenting that so many lives had been sacrificed to a menacing “monster.”

The authorities had taken certain precautions. In the 1850s an ordinance was passed that permitted freight trains to share the streets with pedestrians, horse-drawn vehicles, carriages, streetcars and wagons, on condition that they would observe a speed limit of six miles per hour and that a person on horseback precede the trains to give ample warning of the train’s approach.

Known as West Side Cowboys, these legendary figures waved red flags by day and red lanterns after sundown to alert those moving on street level.

Safety issues on Death Avenue were finally addressed in 1929 when city officials and company operators reached an agreement to move the rail above street level.

On March 24, 1941, twenty-one year old George Hayde led the final West Side Cowboy ride up 10th Avenue. He and his bay horse Cyclone escorted a line of fourteen rail cars loaded with oranges (afterwards Cyclone got a new job at a riding academy). George was the last of the urban cowboys.

The Hascamp Tragedy

In 1908, the Bureau of Municipal Research claimed that over half a century the trains had killed 436 people.

That same year the New York Times reported that during the preceding decade nearly two hundred people from nearby tenements had died, mostly children. The gruesome death of a seven-year-old school boy prompted protests.

On September 25, 1908, Seth Low Hascamp and a group of friends were playing games, climbing on and over the cars of a freight train that had stopped in the middle of 35th Street and 11th Avenue. Neither the conductor nor the brakemen were in their proper places when the train suddenly started forward.

Seth was thrown beneath the wheels and crushed. Although it was illegal for trains to stop at the location in order to avoid such accidents, the city coroner exonerated the crew and blamed the accident on the child’s own negligence.

The decision ignited a wave of anger resulting in a protest march held on the Saturday night of March 24th with five hundred children parading in silence up 11th Avenue carrying placards demanding that freight trains be removed from the city streets. Henry Shroeder, secretary of the newly formed “Track Removal Association,” reported that on dark winter afternoons an average of three school children were killed every month.

As the opposition of residents against train operators intensified, the Association changed its name to the “League to End Death Avenue.” In 1910 it claimed that over the years 548 people had been killed and 1,574 injured on 11th Avenue.

As the opposition of residents against train operators intensified, the Association changed its name to the “League to End Death Avenue.” In 1910 it claimed that over the years 548 people had been killed and 1,574 injured on 11th Avenue.

In spite of continuing protests, it was not until 1929 that the West Side Improvement Project was initiated. Conceived by urban planner Robert Moses, work started on building an elevated track that eliminated the deadly street-level crossings (the last stretch of track on 11th Avenue was removed in 1941).

In 1933, the first train ran on the “West Side Elevated Line” (later renamed High Line). Fully operational by 1934, the line was used to transport millions of tons of meat, dairy and produce. The last train ran along these tracks in 1980 (today, the High Line serves as a mile-and-a-half-long “greenway” with a variety of plants and trees built on the old elevated freight lines).

South of Union Square

In the early twentieth century, inexpensive property in the area south of Union Square attracted painters, writers, small publishers and political organizations that challenged conventional socio-cultural ideals.

Its central area was 14th Street, a vibrant hub of vendors, hawkers and a mass of diverse people navigating the district. Despite the hardships of the Great Depression, the street remained a focal point for urban life throughout the 1930s.

It was here that painters of the Fourteenth Street Group manifested itself. Not so much a “school” as each of the artists developed an individual approach, all were determined to depict the fabric of New York City’s daily life. They came to redefine realist painting by focusing on the surroundings of their namesake street.

Inspired by the Ashcan School, they shared an interest in urban subjects and sought to capture the energy of metropolitan life. Disavowing “elitist” calls for avant-garde experimentation, they persisted with figurative painting, using canvas and brush to call attention to the plight of ordinary people. One of the group’s key figures was Reginald Marsh (1898-1954).

Born in an apartment above the Café du Dôme at 108 Boulevard Montparnasse in Paris, both his American parents were artists. Frederick Dana Marsh was a muralist and Alice Randall Marsh a painter of miniatures (both exhibited work in Paris Salons in the years 1895 to 1899). The paternal grandson of a wealthy Chicago meat packer, Reginald grew up in a privileged environment.

Born in an apartment above the Café du Dôme at 108 Boulevard Montparnasse in Paris, both his American parents were artists. Frederick Dana Marsh was a muralist and Alice Randall Marsh a painter of miniatures (both exhibited work in Paris Salons in the years 1895 to 1899). The paternal grandson of a wealthy Chicago meat packer, Reginald grew up in a privileged environment.

The Dôme had opened in that same year 1898 and in the early decades of the twentieth century it was Paris’s premier gathering place for intellectuals and artists residing in Paris’s Left Bank.

The term “Dômiers” was coined to refer to the cosmopolitan group of creative individuals that gathered there. It was also a meeting place for the growing American literary colony in the capital.

The Marsh family returned to America in 1900, settling in Nutley, New Jersey, and working from a studio at 16 The Enclosure, a property formerly owned by the painter Frank Fowler who had established an artists’ colony there. It nurtured Reginald’s ambition to become an artist. After graduating from high school, he enrolled at Yale University’s School of Art.

Urban Underbelly

After graduation from Yale in 1920, Marsh moved to Manhattan where he was employed as a freelance illustrator for the New York Daily News with the specific task of producing (“raunchy”) sketches of vaudeville performers. The commission gave him an opportunity to hang around the Bowery‘s side-shows, to enter the dance halls of 14th Street, and stroll the beaches of Coney Island.

Marsh was fascinated by the city’s seedier locations. Like a Parisian “flâneur,” he strolled the streets with sketchbook and camera at hand discretely looking for iconic characters – down and out people on Skid Row, burlesque queens, macho men, streetwalkers – that served as source material for the urban panoramas he created at his studio whilst developing a mixed but distinct idiom of fine art, cartoon and caricature.

In 1921, he attended classes at the Art Students League where he studied with other members of what would become the Fourteenth Street Group (John Sloan was one of his teachers). Marsh admired the Ashcan painters for their urban vitality.

In 1925, he joined the staff of the newly founded weekly magazine The New Yorker. As one of its first cartoonists, he helped establish the magazine’s distinctive graphic style.

In 1925, he joined the staff of the newly founded weekly magazine The New Yorker. As one of its first cartoonists, he helped establish the magazine’s distinctive graphic style.

Several of his illustrations refer to Death Avenue, including one in the issue of November 5, 1927, which dramatically depicts the train cutting through the street with a group of jobless men hanging outside a cafeteria. An urban cowboy leads in front of the locomotive.

Marsh would return to Paris on several occasions. In 1928 he revisited the location of his birthplace, dedicating a lithograph to the Café du Dôme’s interior (with the legendary Pernod drinker Homer Bevans as its central figure). On return, he joined his friends working at a studio at 21 East 14th Street (since demolished).

He rejected the modernist movements gaining strength at the time. Instead he focused on depictions of everyday life close to his studio in Lower Manhattan with its theaters and low-cost shopping palaces such as Ohrbach’s or Samuel Klein on Union Square, creating images of jobless men on Manhattan’s heartless streets.

He rejected the modernist movements gaining strength at the time. Instead he focused on depictions of everyday life close to his studio in Lower Manhattan with its theaters and low-cost shopping palaces such as Ohrbach’s or Samuel Klein on Union Square, creating images of jobless men on Manhattan’s heartless streets.

The term Social Realism was used to refer to painters who drew attention to the everyday conditions of working people and the poor and, by implication, who were critical of the social structures that maintained these conditions. Image, content and socio-cultural critique were linked.

Living at 11 East 12th Street during the 1930s, Marsh produced some of his best work having adopted traditional “egg tempera” (employed in early icon painting) as a means to express his creative vision.

Railroad yards and locomotives had preoccupied him throughout his career. Fascinated both by the aesthetics of machines and the menace of their power, locomotives appear time and again in his paintings and prints. He witnessed and recorded the demise of Death Avenue’s crosstown railway line.

Railroad yards and locomotives had preoccupied him throughout his career. Fascinated both by the aesthetics of machines and the menace of their power, locomotives appear time and again in his paintings and prints. He witnessed and recorded the demise of Death Avenue’s crosstown railway line.

In 1937 Marsh created a painting entitled “End of 14th Street Crosstown Line” that juxtaposes two contrasting scenes.

At the forefront a group of demolition workers are tearing up the old railway tracks (the artist must have witnessed the project from close by); in the background picketers have gathered outside Ohrbach’s store demonstrating against its owner who had denied its workers the right to unionize.

(During mass New York City strikes that year workers of over a hundred department stores participated in collective action against their employers).

Marsh’s use of signs, placards and other graphics enhanced meaning and message, making this work a perfect example of what Social Realists intended to achieve in their work.

Marsh’s use of signs, placards and other graphics enhanced meaning and message, making this work a perfect example of what Social Realists intended to achieve in their work.

Reginald Marsh established himself as one of the outstanding chroniclers of pre-war Manhattan. He was to New York City what William Hogarth had been to London and – combined in one – what Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré and Toulouse Lautrec were to Paris.

His paintings, drawings and prints captured the spirit and ambience of the ever-changing metropolis at a deeply troubling yet exciting time in its history.

* The name Hascamp (Haskamp) may be of Dutch or German origin. The boy was named for Seth Low who, from 1881 to 1885, served as Mayor of Brooklyn with the reputation of a municipal reformer. During his time in office he allowed local German beer gardens to stay open in spite of strong opposition of the local puritanical clergy.

Illustrations, from above: West Side Cowboy riding on 10th Avenue (Kalmbach Publishing Co.); the plaque on 10th Avenue commemorating railroads accidents victims; Death Avenue before the High Line was built (Kalmbach); Reginald Marsh’s “Café du Dôme,” signed lithograph, 1928; Marsh’s “Death Avenue,” cartoon with urban cowboy in The New Yorker, November 5, 1927; Marsh’s, “Death Avenue,” 1928. (Whitney Museum of American Art); Marsh’s, “End of 14th Street Crosstown Line,” 1936 (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts); and Reginald Marsh plein air sketching on 14th Street, Manhattan, 1941.

Recent Comments