For Europeans planning or being forced to migrate, the concept of the United States as a virtually border-less society remained alive until the passing of the Immigration Act of 1917 (this was not the case for other groups). It offered an opportunity to governments to “shovel out” troublesome subjects.

For Europeans planning or being forced to migrate, the concept of the United States as a virtually border-less society remained alive until the passing of the Immigration Act of 1917 (this was not the case for other groups). It offered an opportunity to governments to “shovel out” troublesome subjects.

The German term Übersiedelung (literally: relocation) was used by officials of the Kingdom of Hanover to describe the practice of exiling “unwanted” subjects to America. From the early 1830s to 1866 (when Hanover was conquered by Prussia), some three thousand individuals – most of them petty criminals or paupers – were expelled from the territory.

Their coerced removal served as an alternative to imprisonment and was, therefore, presented as a mutually beneficial course of action. Criminal law was applied to enforce emigration.

Many Americans resented accepting German speaking outlaws as immigrants. It was not their first conflict with the Kingdom. George III, the Hanoverian British monarch, had in the eyes of colonists overreached his power with a hard-line approach to the American Revolution.

The Declaration of Independence accused him explicitly of tyranny. Britain’s long history of exiling offenders to America had started a century before the ascendancy of the Hanoverians to the British throne in 1714.

In 1615, King James I (1566-1625) allowed English courts to send convicts to the colonies as a way of alleviating the nation’s criminal population. Deported convicts were set to work on plantations in Virginia and Maryland, provide cheap labor and populate remote areas.

By 1699, an estimated 2,300 felons were removed from jails and workhouses, but the system of penal transportation had to cope with rising opposition from within the colonies. The snake began to rattle its tail.

Bloody Code

Enacted in England from the seventeenth century onward, the “Bloody Code” was a set of penal laws that mandated the death penalty for such crimes as murder, arson, forgery, stealing cattle or sheep, pick-pocketing or stealing from a shipwreck. Dating back to 1688, the misdeeds punishable by death initially amounted to fifty; by 1815 the number had increased to over two hundred.

The Code reflected the harshness of a system that responded to social changes – urbanization, population growth, increased poverty and crime. It was used to maintain the status quo and suppress dissent.

As criminal justice relied upon fear of retribution, the public display of executions was crucial. If punishment was to set an example to onlookers, then the execution should be dramatic. The death penalty was both a ritual and performance.

As criminal justice relied upon fear of retribution, the public display of executions was crucial. If punishment was to set an example to onlookers, then the execution should be dramatic. The death penalty was both a ritual and performance.

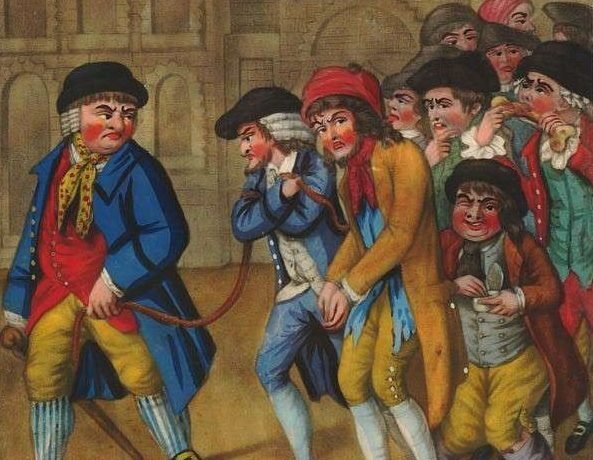

Over time, “hanging days” deteriorated into drunken orgies of a rowdy and boisterous mob. The regularity of executions led to hanging-fatigue amongst the public and a hardening of its moral senses. Juries became increasingly reluctant to convict defendants for minor misdemeanors, leading to a decline in the effectiveness of the system. It was feared that law and order were at stake.

In 1615, King James I had authorized the process of transporting convicts to the American colonies where they could be profitably employed on the plantations. By the end of the century, the chaotic process had ceased to function as colonies were unwilling to accept convicts and ship owners reluctant to take felons on board.

In response, Parliament passed the Transportation Act of 1717 to create a systematic way of deporting convicts. It formalized the process, allowing courts to sentence felons to either seven or fourteen years of exile as an alternative to capital punishment.

The Act significantly increased the number of deported convicts and established a structured system for their transport to the colonies. Landing along the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, they were put to work in the tobacco fields or at shipbuilding yards. Completion of the imposed sentence had the effect of a pardon; the punishment for attempted escape was death.

Between the passing of the 1717 Transportation Act and the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, it is estimated that over 52,000 convicts were deported from overcrowded prisons and workhouses to be sold to the highest bidder. Convicts may have made up a quarter of British immigrants to colonial America during that period.

Many observers judged transportation a means of “draining the Nation of its offensive Rubbish.” Lawmakers considered exile an appropriate punishment; others regarded it an offer of rehabilitation, giving felons the opportunity of making a new life.

This applied to female convicts in particular. Upon arrival in the colonies, they were sold as indentured servants, facing harsh working conditions and mistreatment whilst suffering separation from their own families.

This applied to female convicts in particular. Upon arrival in the colonies, they were sold as indentured servants, facing harsh working conditions and mistreatment whilst suffering separation from their own families.

Daniel Defoe’s novel The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders (1722) is the personal history of a bigamist, prostitute and thief. Born in London’s Newgate Prison to a convict mother and having lived a life of deprivation, she spent eight years as a transported felon in Virginia. Moll Flanders died a penitent.

The novel has been interpreted as a conversion narrative, a piece of propaganda supporting transportation’s “redemptive” powers. In his preface the (Puritan) author promised his reader a serious message, but the storyteller proved stronger than the moralist. It is not so much a story of salvation, but a gripping tale of survival in the urban jungle.

From Satire to Symbol

Exporting criminal miscreants to North America was a policy celebrated as a “way to help the colonies grow.” Settlers were dubious. Although costly, slaves were more attractive to potential buyers than deportees as they were considered stronger, healthier and less defiant. In addition, they were sold for life whereas most convicts served a seven-year term.

Once English ships arrived at their destination, deportees were lined up for inspection by interested parties. All “unsold” convicts were offered as a group to dealers (known as “soul-drivers”). Chained together they were marched into the country and sold at remote locations.

While plantation owners may have welcomed the availability of cheap labor, other Americans were anxious about the influx of convicts. Authorities in Virginia and Maryland tried repeatedly to prevent the “trade” in felons, but their legal measures were overturned by representatives of the Crown.

While plantation owners may have welcomed the availability of cheap labor, other Americans were anxious about the influx of convicts. Authorities in Virginia and Maryland tried repeatedly to prevent the “trade” in felons, but their legal measures were overturned by representatives of the Crown.

In The Scarlet Letter (1850), a novel set in the Puritan Bay Colony, Nathaniel Hawthorne observed that however lofty the ideals of early settlers might have been, the first practical step they took was to “allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison.” Boston Gaol [Jail] was erected in 1635, the city’s first “house of detention” (rebuilt in 1704 on the same site).

Opponents of penal transportation would find support of an eloquent spokesman. On May 9, 1751, using the pen name “Americanus,” Benjamin Franklin published a satirical article in The Pennsylvania Gazette entitled “Rattlesnakes for Felons” in which he praised England for its generosity by which “all the Newgates and dungeons in Britain are emptied into the colonies.”

As a token of appreciation he suggested that the nation should present England with rattlesnakes in exchange. Behind the satire there was a message. Emptying jails into American settlements was an act of contempt. Benjamin Franklin introduced the rattlesnake into political debate.

As the species was unknown in the Old World, European authors and French academics in particular were fascinated by rattlesnakes. The study of snakes saw a mix of empirical observation and lingering traditional beliefs. The myth of the “joint snake” persisted, suggesting the ability of reptiles to regenerate their bodies after being severed. It was perpetuated in emblem books.

In 1685, Nicolas Verrien published a Recueil d’emblèmes (a new edition appeared in 1724), a collection of emblems that includes a sample of a snake cut in two parts with the motto: “Un Serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir” (A serpent cut in two. Either join or die).

In 1685, Nicolas Verrien published a Recueil d’emblèmes (a new edition appeared in 1724), a collection of emblems that includes a sample of a snake cut in two parts with the motto: “Un Serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir” (A serpent cut in two. Either join or die).

Franklin admired the genre for its use of imagery to communicate complex ideas. He was most likely familiar with Verrien’s emblem. A similar tale circulated in the English colonies: a cut serpent would come alive if the pieces were joined back together before sundown.

Academic interest advanced research. In 1705, Jamestown-born planter Robert Beverley published his History and Present State of Virginia (three French editions were published between 1707 and 1718) in which he called for a better understanding of the rattlesnake’s behavior.

Fears expressed by Europeans were unjustified. He insisted that the viper was not a threat; it would only attack if disturbed. The rattlesnake image produced by Suffolk-born Mark Catesby in The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1731/43) further excited the scientific world.

All these trends play in the background of a cartoon “Join, or Die” in The Pennsylvania Gazette of May 9, 1754, presenting a sliced up rattlesnake in the shape of a colonial map. Its engraver has not been identified, but Benjamin Franklin formulated the message behind what he called his “Emblem.”

All these trends play in the background of a cartoon “Join, or Die” in The Pennsylvania Gazette of May 9, 1754, presenting a sliced up rattlesnake in the shape of a colonial map. Its engraver has not been identified, but Benjamin Franklin formulated the message behind what he called his “Emblem.”

Alluding to the old myth, the cartoon shows a snake in eight pieces, each representing part of colonial North America. Franklin made a call for the colonies, from New England at the snake’s head to South Carolina at its tail, to unite in battle during the French and Indian War or face defeat.

Metaphor & Banner

On the eve of the American Revolution, the snake image appeared again in print. Boston-born printer and journalist Isaiah Thomas used his newspaper The Massachusetts Spy (established in 1770) to rally support in the struggle for self-governance.

He published the first eyewitness accounts of the Battles of Lexington and Concord which turned out to be pivotal events in the Revolution. At the head of the newspaper’s first page, Thomas displayed the snake confronting the dragon symbolizing England with the phrase “Join or Die.”

The rattlesnake turned into a mascot. Once again, Franklin played a part. On December 27, 1775, he issued another anonymous article in the Gazette. Signed “An American Guesser,” it was entitled “The Rattlesnake as America’s Symbol.”

The rattlesnake turned into a mascot. Once again, Franklin played a part. On December 27, 1775, he issued another anonymous article in the Gazette. Signed “An American Guesser,” it was entitled “The Rattlesnake as America’s Symbol.”

A scientist at heart and aware of recent research developments, the author stressed that the rattlesnake tends to avoid confrontation. If provoked or disturbed, however, it will respond in a lethal manner. Franklin’s reference to reptile behavior proved to be a perfect tool for political discourse, both as a metaphor and a prophecy.

The rattlesnake became emblematic of American pride and vigilance.

Almost simultaneously Christopher Gadsden, a native of South Carolina and a Colonel in the Continental Army, designed a flag that displayed a coiled timber rattlesnake with fangs exposed, ready to strike. It contained the words “Don’t Tread on Me” upon a bright-yellow background.

Almost simultaneously Christopher Gadsden, a native of South Carolina and a Colonel in the Continental Army, designed a flag that displayed a coiled timber rattlesnake with fangs exposed, ready to strike. It contained the words “Don’t Tread on Me” upon a bright-yellow background.

In 1775, George Washington officially established the Continental Navy to intercept English supply ships. Commodore Esek Hopkins was handed the banner for display on his flagship USS Alfred. Known ever since as the “Gadsden Flag,” it was a telling extension of Franklin’s metaphor.

During the uprising, the rattlesnake represented a desire for national unity and independence. It appeared in printed caricatures, newspapers and paper money as well as on flags and buttons.

The Continental Congress incorporated the reptile into the seal for the Board of War & Ordnance in 1778. That same year, Georgia issued a $20 bill featuring a rattler accompanied by the motto “Nemo me impune lacesset” (No one will provoke me with impunity). Snakes slithered everywhere.

The American Revolution ended the deportation of English convicts to the United States. Colonial ports ceased accepting convict ships. The Transportation Act was suspended that same year with the introduction of the Criminal Law Act, otherwise known as Hard Labour Act. Australia became the new penal colonial location.

The American Revolution ended the deportation of English convicts to the United States. Colonial ports ceased accepting convict ships. The Transportation Act was suspended that same year with the introduction of the Criminal Law Act, otherwise known as Hard Labour Act. Australia became the new penal colonial location.

When in 1782 Britain was coming to grips with defeat by the rebels and forced to negotiate a peace treaty in Paris, English cartoonists portrayed the United States as a vengeful and menacing rattlesnake.

While the bald eagle was – against Benjamin Franklin’s wish – ultimately chosen as a national symbol, the rattlesnake continued to be used in various other contexts. To this day, either perverted or not, it remains in certain circles (in 2010, the Tea Party adopted the Gadsden flag as its banner) a symbol of American identity.

Illustrations, from above: Detail from “A Fleet of Transports under Convoy,” outside London’s Newgate prison (British Museum); a relatively easy punishment under the bloody code; Illustration from Moll Flanders, from an 18th-century chapbook; “Mother Brownrico Flogging Her Apprentice in the Cellar”; Mark Catesby, watercolor of a timber rattlesnake in The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, 1731/43 (Plate 41); Franklin’s rattlesnake in The Pennsylvania Gazette of May 9, 1754; The Gadsden flag depicting a coiled timber rattlesnake ready to strike; and the Seal of the Board of War & Ordnance, adopted by the Continental Congress in 1778.

Recent Comments