My grandfather Dwight James Baum (DJB) is Little Falls, Herkimer County, NY’s most-famous architect and one of its most-famous sons. While I may be partial to that view, it’s shared by many experts.

My grandfather Dwight James Baum (DJB) is Little Falls, Herkimer County, NY’s most-famous architect and one of its most-famous sons. While I may be partial to that view, it’s shared by many experts.

In the 2008 reissue of The Work of Dwight James Baum, edited by William Morrison in 1927, Ron McCarty, Curator and Keeper of Ca’ d’Zan (a Mediterranean revival residence on Sarasota Bay in Florida designed by DJB) noted that “in 1923, the Architectural League of New York awarded the Gold Medal to Dwight James Baum. Aged 37 and practicing independently for a mere eight years, Baum was the youngest architect ever to receive the coveted honor.

“Nine years later in 1932, the American Institute of Architects similarly honored Baum for designing the best two-story house in the United States between 1926 and 1930. The gold medal was awarded to Baum by President of the United States Herbert Hoover.

“These were singular distinctions for any architect, but all the more so when awarded to the Upstate New York son of a shoe salesman and generations of Mohawk Valley farmers.”

Others have heralded him as an architect of choice in The Gilded Age. Ever admiring of a local son, the Little Falls Evening Times declared him “One of the nation’s greatest architects.”

When the Museum of the City of New York created its 2011 exhibit and book American Style: Colonial Revival and the Modern Metropolis, it had the full panoply of New York City architects from which to choose. Yet, 72 years after his death, the Museum chose to feature the life and prodigious work of DJB.

When the Museum of the City of New York created its 2011 exhibit and book American Style: Colonial Revival and the Modern Metropolis, it had the full panoply of New York City architects from which to choose. Yet, 72 years after his death, the Museum chose to feature the life and prodigious work of DJB.

According to a family historian, Louie Baum of Little Falls, the Baum ancestors came to the Little Falls area in the mid-1700s, along with many other Palatines. Little Falls was the frontier at that time, and the Palatines were invited in to be a buffer between the English colonists and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and their French allies to their west.

Philip Baum had three sons, including Philip F. Baum II (my ancestor), the Rev. John Baum (ancestor to author L. Frank Baum), and Jacob P. Baum (Louie Baum’s ancestor). My ancestor Philip F. Baum had 10 children, six of whom were sons. One of the youngest was Fayette Baum, DJB’S father who married Alma Ackerman.

DJB was born on June 24, 1886 at the 142-acre Baum homestead on the Wright Corners-Newville Road just south of Little Falls. He always considered Little Falls his hometown.

He hung several prints of Little Falls in his office and home in The Bronx (in elite Fieldston in Riverdale) and collected books about Mohawk Valley history. In the 1920s, he hired a professional genealogist to research the family’s history which documented his Mohawk Valley ancestors, some of whom had fought at the Battle of Oriskany. DJB joined the Sons of the American Revolution.

From The Farm to Little Falls & Syracuse

In 1892, when DJB was six, his father Fayette retired from farming and moved the family to downtown Little Falls where he owned and ran the Rockton Shoe Store at 528 East Main Street. DJB was educated in Little Falls public schools through his second year of high school.

According to his obituary in the Little Falls Evening Times, as a schoolboy he was a carrier for that newspaper. In 1902 when DJB was 16, the family moved to Syracuse.

Following other family members, Fayette took up employment in the lubricating oil business. It was there that Fayette and DJB might have crossed paths with older Baum cousins including L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), author of the Wizard of Oz.

An obituary of Fayette Baum describes his employment in Syracuse: “For 20 years he was eastern representative of the Union Oil Company of Erie, Pa., resigning his position when he was stricken ill two months ago.” He died at age 77 in 1933 in his home at 204 Onondaga Avenue, Syracuse.

The Syracuse Baum cousins had wide-ranging interests in oil fields, oil products, and real estate. The patriarch of the Syracuse branch had been Benjamin Ward Baum, who like Fayette, was a grandson of Philip and father of L. Frank Baum.

The Syracuse Baums’ highly successful business empire suffered mightily from a series of business and personal disasters. Benjamin Ward Baum was severely injured while driving a buggy behind a newly trained colt who was startled and bolted – the buggy was wrecked against a hitching post.

Benjamin was thrown to the street and experienced a severe head injury. Likely suffering from traumatic brain injury, he traveled to Germany to seek advanced medical care. When he returned, he found that his finances had been mismanaged and was forced to sell numerous assets to raise cash.

Among them was a 160-acre commercial farm. In an amazing coincidence, he sold that farm to the Crouse family of Syracuse. While no one could have known it at the time, decades later in 1912, Dwight James Baum would marry Katharine Crouse. Benjamin Ward Baum died two years after his accident in 1887, when Dwight was only a year old.

L. Frank Baum continued leadership in the reduced family businesses after his father’s and brother Will’s deaths. However, he became distracted from his sales role when his wife, Maud,almost died after giving birth to their third son. Eventually, L. Frank Baum returned to the road developing sales for Baum’s Castorine axle oil.

L. Frank Baum continued leadership in the reduced family businesses after his father’s and brother Will’s deaths. However, he became distracted from his sales role when his wife, Maud,almost died after giving birth to their third son. Eventually, L. Frank Baum returned to the road developing sales for Baum’s Castorine axle oil.

While he was traveling, and his wife was recuperating in Fayetteville, the Baums’ Syracuse office and manufacturing were entrusted to Uncle Doc Baum. Uncle Doc’s real name was Adam Baum (yes, I heard that joke many times in school, but this was well before invention of the atom bomb).

Uncle Doc had served two years in the Civil War as a surgeon with the 50th Engineers decades earlier. His management skills were suspect, and his health was so poor that he delegated oversight of the business to a clerk. One day in 1888, L. Frank Baum returned from a sales trip to the Baum Castorine Company office to find a shocking scene when he unlocked the door: he found the clerk dead, his lifeless body sprawled across a desk.

The revolver with which he had shot himself was still in his hand. The resulting investigation revealed that much of the company’s capital had been gambled away by the clerk, and the company’s bills had been left unpaid. L. Frank Baum sold Baum’s Castorine to Marcus and Howard Stoddard.

The Stoddards kept the signature “L.F. Baum” on the label and kept the Baum name in the company’s name for another 30 years. Baum’s Castorine is still in business today, selling its lubricants from offices in Rome, New York.

The Architect & The Debutante

After graduating from Central High School in Syracuse, Dwight James Baum attended and graduated from Syracuse University with a degree in Architecture in 1909.

“Since then, his rise in the field of architecture has been nothing short of phenomenal,” the University’s Alumni News later wrote. “Despite the national acclaim accorded him in his field, Mr. Baum always kept in close touch with Syracuse and with his Alma Mater.”

DJB worked his way through Syracuse University by selling display advertising on desk blotters. Despite his work commitments, he was said to have shone as a star student. Among his many honors as an undergraduate, was a University architecture fellowship and election to three different honor societies.

In 1934, 26 years after his graduation, Syracuse University honored him with an honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts. (My husband and I both wore DJB’s doctoral mortarboard at our respective graduations from law school.)

As his professional success grew, DJB was retained by Syracuse University to partner with another legendary architect, John Russell Pope (1874-1937), in mapping out a 50-year building and University expansion program. In conjunction with that program, DJB was appointed architect for the University’s College of Medicine, the Maxwell School of Citizenship, and Hendricks Chapel, where DJB’s funeral would be held after his untimely death.

As his professional success grew, DJB was retained by Syracuse University to partner with another legendary architect, John Russell Pope (1874-1937), in mapping out a 50-year building and University expansion program. In conjunction with that program, DJB was appointed architect for the University’s College of Medicine, the Maxwell School of Citizenship, and Hendricks Chapel, where DJB’s funeral would be held after his untimely death.

But in 1910, the year after his graduation, it was on a Syracuse streetcar where DJB’s life was changed. As the story goes, he witnessed a young woman hassled by a group of schoolboys and stepped between them. The young woman thanked him and he offered to sit with her to her stop.

The woman was Lucia Katharine Crouse, a daughter of one of the richest families in Syracuse, and my granddaughter. Her family was suspicious of their debutante daughter having been “picked up” on a streetcar by a young man of high academic achievement but modest means – they arranged for her to go to Europe for a year with her aunt. When she returned she insisted to her parents that she wanted to marry DJB.

The bridal showers and luncheons were held, all breathlessly described in local papers. The wedding took place in “the old Crouse mansion” on January 3, 1912. The papers described the nuptials in great detail, noting that in the dead of winter, the Crouses had filled their home with thousands of flowers. After their wedding, the young couple moved to an apartment on Riverside Drive in New York City.

A Noted New York Architect

DJB opened his own practice only six years after his university graduation. He was noticed and hired by financier Edward C. Delafield to do some alterations to his mansion.

Delafield was apparently so pleased with the young architect’s work that he encouraged him to build his architectural office in Delafield’s new development, Fieldston, which Delafield had carved out of his family’s Riverdale-on-Hudson lands in The Bronx, about ten miles north of mid-town Manhattan.

It’s one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the City and one of only a few that are entirely privately owned. Delafield referred those purchasing land from him to the on-site DJB and so he attracted many clients.

DJB built his own family’s home in Fieldston in 1913 and then a larger Fieldston home he named “Sunnybanks” in 1916 at 5001 Goodrich Avenue, on one of the highest points in the City and directly across the street from Delafield’s mansion.

DJB built his own family’s home in Fieldston in 1913 and then a larger Fieldston home he named “Sunnybanks” in 1916 at 5001 Goodrich Avenue, on one of the highest points in the City and directly across the street from Delafield’s mansion.

Into the 1930s DJB designed at least 150 residences in Fieldston and Riverdale in the Colonial Revival, Greek Revival, Georgian, and Mediterranean styles. To this day, these homes are advertised for sale as “Baum homes.”

It was during this time that DJB also designed four homes for prominent Little Falls families – John Zoller on Diamond Street, Congressman Homer P. Snyder on North Ann Street, Gordon Little on Burwell Street, and Frank Simpson on Salisbury Street.

DJB has also been been noted for “his respect for ecology before anyone thought of such things, when the words ‘ecology’ and the ‘environment’ were scarcely known,” according to architect Ludwig P. Bono.

As noted earlier, the American Institute of Architects honored DJB in 1932 for designing the best two-story house erected in the United States between 1926 and 1930 for one of his Fieldston houses. He was summoned to the White House where President Herbert Hoover presented the medal himself.

A Star Architect in Florida

One of the homes for which DJB is best remembered is Ca’ d’Zan (Venetian for “House of John”), which DJB designed for Ringling Brothers – Barnum & Bailey Circus owner John Ringling and his wife Mable. The Ringling job in 1922 occurred at the start of Florida’s land boom and marked the beginning of DJB’s career as one of Florida’s star architects.

“At a time when Sarasota was booming, Baum’s arrival from New York helped raise its architectural profile,” McCarty once said in an interview. “He was their most prominent of the architects of the 1920s. He had a national reputation.”

In 1924, DJB made a long trip to Venice, Italy, with the Ringlings and discovered that Mable Ringling had strongly held artistic tastes which did not always win praise from her architect. She had spent years researching exotic marbles, glass, wood paneling and Venetian palazzos, and wanted them all in her Sarasota mansion. She directed DJB to create numerous architectural renderings, with so many changes during construction that he had to adjust his fee structure.

Antique architectural elements were shipped from Venice to Sarasota by the ton. The 36,000-square-foot mansion on the shore of Sarasota Bay was completed in October 1925.

Antique architectural elements were shipped from Venice to Sarasota by the ton. The 36,000-square-foot mansion on the shore of Sarasota Bay was completed in October 1925.

In addition to its many architectural features, Ca’ d’Zan features an 8,000 square-foot marble terrace where Mable and her pet cockatoo might greet guests arriving by water on her private Venetian gondola. At Ringling parties musicians would play on the gondola in the Bay with the sun setting behind them.

After the mansion and its outbuildings were completed in 1925, DJB continued his association with John Ringling and with Ca’ d’Zan’s builder, Owen Burns. He opened a Sarasota office to produce designs for villas in Ringling’s own large land developments in the Sarasota Keys and in downtown Sarasota.

Among these were the Owen Burns Realty Company Building (1925), where Burns and DJB had their offices, the El Verona Hotel (1926), owned by Ringling and later known as Ringling Towers, the Sarasota Times Building (1926), and the Sarasota County Court House (1927). Additional projects were on the drawing boards when the 1926 hurricane and then the 1929 market crash halted Florida’s real estate boom.

Mable Ringling died in 1929 and John Ringling died in 1936, willing Ca’ d’Zan and their art collection to the State of Florida. Ca’ d’Zan remains a major tourist attraction. Outside of Fieldston and Riverdale, NY, Sarasota has the largest concentration of buildings in the country designed by Baum.

DJB in the Great Depression

In the 1920s and the lean Great Depression years of the 1930s, DJB expanded his practice to include more government, institutional, and commercial commissions. These included buildings at Syracuse University, Wells College, Middlebury College, Clarkson College, the Flushing, NY, Post Office and the Federal Building there, as well as the hospitals in Syracuse and in Little Falls.

In the 1920s and the lean Great Depression years of the 1930s, DJB expanded his practice to include more government, institutional, and commercial commissions. These included buildings at Syracuse University, Wells College, Middlebury College, Clarkson College, the Flushing, NY, Post Office and the Federal Building there, as well as the hospitals in Syracuse and in Little Falls.

“During the depression, many architects had to leave the profession to support themselves. DJB was one of the few architects in the New York area who was able to keep his office open… because of his close association with the Architectural League of New York,” Mcarty reports.

“From the early 1920s DJB had been active in preservation activities. He photographed historic structures and wrote articles on preservation. Because of this interest, the Architectural League chose DJB’s office for work projects to support unemployed draftsmen and designers. Among the projects undertaken at this time was the research and documentation of historic buildings in Barrytown, New York, and Charleston, South Carolina.”

DJB worked tirelessly on committees throughout the Depression to help struggling architects and draftsmen. He famously kept his entire Fieldston draftsmen staff employed during the hard times by assigning them to work in shifts and on historic preservation projects. The Museum of the City of New York in a 2011 exhibit hailed DJB for his Depression-relief work including promoting sales of sets of fine dinnerware featuring images of different architects’ designs.

At a more personal level, when the brother of the family’s long-time cook Clara showed up at Goodrich Avenue homeless and unemployed in the depths of the Depression, DJB welcomed him into the household and assigned him odd jobs in exchange for Clara’s home-cooked meals and a warm bed.

In 1929, DJB was engaged as architectural writer and editor for Good Housekeeping magazine, where he published numerous articles on the virtues of good design in homes. His long association with Good Housekeeping lasted the rest of his life and led to several unique assignments in the Depression years.

Among other things, DJB was asked by Good Housekeeping to design model houses of the future for the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago and the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Unlike the mansions for which he was famous, he created Art-Moderne homes designed to contain all the most advanced appliances and conveniences for what were likely to be servant-less homes of the future.

At the New York World’s Fair, he also served as architect for both the Home Furnishings and the YMCA pavilions. The last was an outgrowth of his major role as architect of the still-celebrated West Side YMCA on Manhattan’s West 63 rd Street, which was completed in 1930. The 16-story building spans a full block from 63rd to 64th streets and houses three gyms, two swimming pools, and dormitory quarters for 600. It’s one of his most famous commissions and still in use.

DJB and Katharine had three sons, Dwight Crouse (known as Bill), John Leach, and my father, Peter Ackerman, all now deceased. I was told some of their fondest memories were of extended family trips to such destinations as Cuba, California, Canada, Alaska, Russia, Germany and, of course, Syracuse.

These trips often included cross-continental drives in two cars. Katharine liked Packards and drove her own car. DJB bought himself a movie camera and photographed and filmed architecture everywhere they went. (I have inherited a number of those architectural photographic prints DJB made of those trips.)

These trips often included cross-continental drives in two cars. Katharine liked Packards and drove her own car. DJB bought himself a movie camera and photographed and filmed architecture everywhere they went. (I have inherited a number of those architectural photographic prints DJB made of those trips.)

My father, Peter Ackerman Baum, was in his senior year boarding at The Taft School when he got the news that at 5:40 pm on December 13, 1939, while running down New York City’s West 45th Street to catch the bus home to Fieldston, DJB suffered a massive heart attack and died immediately on the sidewalk in front of the Hotel Astor.

NYC Police Officer Joseph P. Maguire and the doorman understood that the victim was a celebrity and immediately summoned Dr. Bouton from Roosevelt Hospital, who pronounced him dead.

The Little Falls Evening Times reported that “[o]ne tragic feature of the death of Mr. Baum was the fact that his brother-in-law Jerome D. Barnum, publisher of the Syracuse Post-Standard, and President of the American Association of Newspaper Publishers, was attending a board of directors meeting of the American Association” at the nearby Cornell Club from which Barnum was summoned to identify his brother-in-law’s body. “Mr. Barnum’s wife and Mrs. Baum are sisters.”

Funeral services were held at Riverdale Presbyterian Church and again a few days later in the Hendricks Chapel at Syracuse University which DJB had designed. He was interred in Oakwood Cemetery next to the legendary Crouse Boulder, traditional burial site of his wife’s family.

The architectural world was as shocked as DJB’s family at the sad news. Condolences poured in from around the country. Many of those messages spoke not just to the character of the man, but to his portfolio of architectural achievement. With his death at the age of 53, he had been a practicing architect for just 25 years.

Victoria Baum Bjorklund is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.

Read more about architecture in New York State.

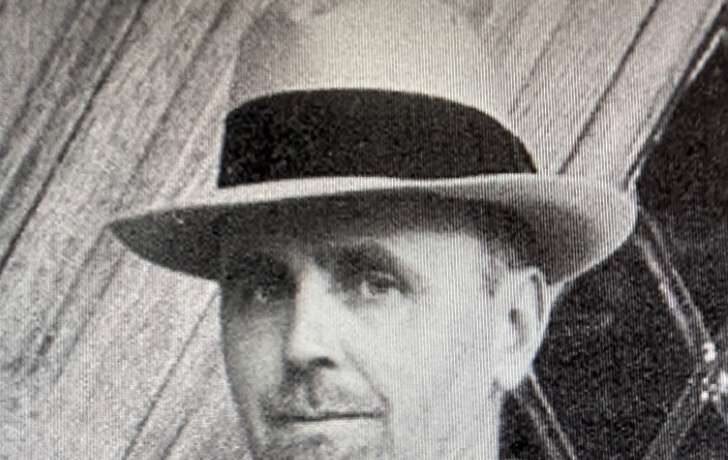

Illustrations, from above: Portrait of Dwight James Baum; The Work of Dwight James Baum (2008); an advertisement for Baum’s Castorine Company of Syracuse; Hendrick Memorial Chapel, Syracuse University; “Sunnybanks,” home of Dwight James Baum in Riverdale; Ca’ d’Zan in Sarasota; Baum-designed Little Falls Hospital; and DJB with his young son Peter Ackerman Baum (the author’s father) at the Berlin Zoo, 1928.

Recent Comments