On December 18, 1860, John J. Crittenden of Kentucky introduced a compromise plan to the U.S. Senate. Just two days later, South Carolina would become the first state to secede from the Union, and within six weeks, six more Southern states would follow suit. But while Dixie fire-eaters were driving their states pell-mell toward disunion, Senator Crittenden and other moderates were working to broker a sectional adjustment — one that could, they hoped, soothe Southern fears about Abraham Lincoln’s election and stay the secession tide in the South.

The Crittenden Compromise would be central to these efforts during the winter and spring of 1860-1861. It represented an attempt to settle the slavery question once and for all, drawing on the tradition of grand settlements like the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850. Indeed, the cornerstone of Crittenden’s plan was a constitutional amendment that would divide the remaining Western territories along the old Missouri Compromise line, barring slavery above and protecting slavery below the 36º 30’ parallel.

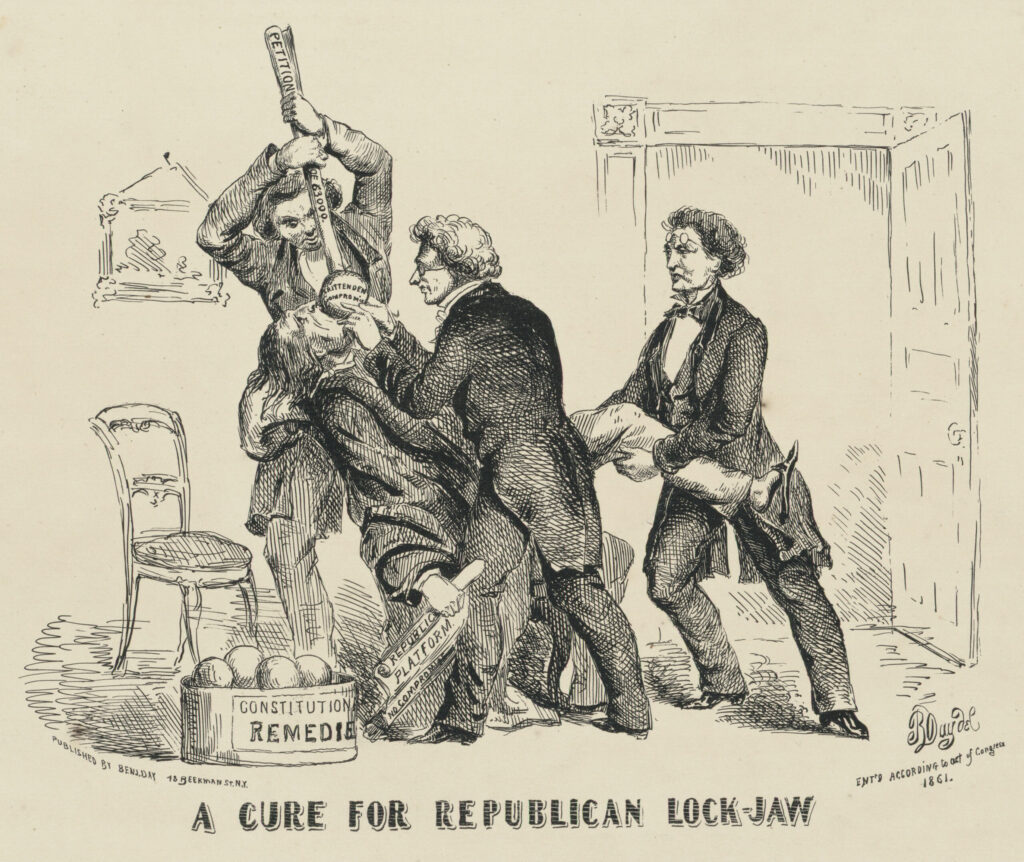

Moderates like Crittenden hoped that this might be enough to secure the loyalty of the remaining Southern states to the Union. This might, in turn, make Republicans more willing to let the secession crisis play out, and it might eventually make the seceded states more willing to return to the Union. Yet most Republicans, including Lincoln, refused to countenance any further extension of slavery into the territories. Attempts by moderates to push through the Crittenden Compromise repeatedly foundered against this opposition.

Compromisers struggled, too, against the opposition of Southern secessionists, who argued that it did not do enough to protect slavery from the threat of an empowered Republican Party. Over the course of the secession crisis, it became clear that the leaders of the seceded states had no interest in negotiation or returning to the Union. Southern rights advocates in the states that had not seceded also complicated the project of compromise; their demands for more concessions meant there was no consensus around Crittenden’s or any other compromise measure even in those states.

(Library of Congress)

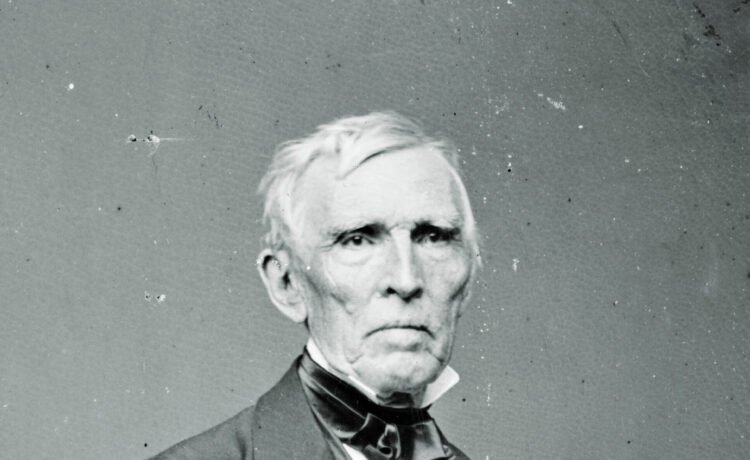

One such antagonist was Virginia’s John Robertson, a prominent Democrat and judge from Richmond. The state legislature sent him as a commissioner to the seceded states in early 1861, and he returned with assurances of the new Confederate States’ sympathies with Virginia. They are “bone of her bone, and flesh of her flesh,” he reported.

The outbreak of fighting at Fort Sumter on April 12 provided the push for which many Southern hardliners had been hoping. Abraham Lincoln responded by issuing a call for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion in the South, and in short order Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee seceded and joined the new Confederacy. The start of the war seemed to signal triumph for militants like Robertson and disaster for moderates like Crittenden. Yet neither man would accept this as the outcome of his labors.

Robertson wrote a letter to Crittenden near the end of April that highlighted just how uncertain the future appeared in that moment. Robertson refused to believe that the collision at Fort Sumter necessarily meant war —and rejected, moreover, the idea that war would accomplish the ends of either side in the conflict. He thus suddenly and unexpectedly found his own goals aligned with Crittenden’s, and Robertson begged the old Kentuckian to renew his efforts at conciliation.

From Robertson’s point of view, civil war did not seem inevitable, even when armies were massing on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. The situation represented a dramatic escalation, to be sure, but in the context of the decades-long sectional crisis over slavery (one that had at other points erupted in violence), observers like Robertson could imagine outcomes other than intestine war.

John Robertson to John J. Crittenden, April 28, 1861

Dear Sir,

No man could have more earnestly striven than yourself to [resolve] the feuds, whose increasing fury, already advanced to the stage of murderous conflict, threatens to involve thirty millions of men in the horrors of civil war. However I may have differed with you, looking from a Southern view, as to the acceptability of the terms of adjustment you proposed, I never doubted that you regarded them as just, or, at least, as preferable to the evils otherwise to ensue, and as the best which could possibly be obtained. The event has proved that, moderate as they were, the ruling faction [the Republican Party] would be content with none but such as would degrade the South. Wellnigh desperate is the condition to which that faction has reduced this country. The fact now stares them in the face that the Union is dissolved beyond all hope of restoration, at least, in our day. Yet they are threatening to preserve the Union by force. They read the riot act to millions of men, nay, to sovereign States, who are to be coerced into friendship by their foes at the point of a bayonet. But, waving all recrimination, not insisting on the absurdity of the idea, or the impossibility of reducing the South to an ignominious submission, or the certainty that their subjugation, if possible, would defeat the very object their enemies profess to desire (namely, the preservation or restoration of the Union), by converting States into vassal provinces (in that character alone can they remain or enter into it), let us inquire if there are no means by which the anticipated consequence of our family jars (now an accomplished fact), the separation of the States, may be recognized by the ruling faction at Washington, without deliberately repeating the most atrocious crime, and steeping their hands still deeper in the blood of their brethren. A word from the long-eared god [Lincoln], who now holds in his hands (as he imagines) the destinies of the country, would be enough. He has only to say, “Let there be peace,” and there will be peace. But he and the murderous gang whom he consults already cry ‘Havoc!’ And let slip the dogs of war. And yet the star of hope still twinkles in the clouded firmament. Preposterous as is the idea of peaceful union or reunion, there may still be a peaceful separation; and it is to yourself, sir, who, if allowed to do so, I will still regard, notwithstanding the marked difference of our political sentiments, as a valued friend,—it is mainly to you I look for effecting so glorious a consummation. I do not desire that my name should be connected with an effort which you may, most probably, consider utterly idle, and which, should you think worth trying, be more apt to succeed without it. Before going further at present, permit me to inquire whether it will be agreeable to you to entertain the thoughts which, after much anxious reflection, have entered into, and taken firm possession of, my mind.

It is proper to say that my appeal to you is wholly without the sanction or knowledge of any constituted authorities, State or federal. It has been suggested even but to two individuals; in the judgment of one of them you would yourself repose great confidence. I have received decided encouragement to make it.

An immediate answer, if convenient, will greatly oblige me.

With great and respectful regard, yours,

John Robertson

For all of their disagreements, Crittenden must have found some encouragement in Robertson’s kindred desire for peace. Robertson still seemed to hope that secession could be accomplished peacefully, but Crittenden saw peace as a means to promote compromise and reunion, as well. A month after the former’s letter, Crittenden would preside over a convention in Frankfort, Kentucky, which would renew calls for Crittenden’s compromise as a basis for sectional adjustment. “Whether any such constitutional guarantees would have the effect of reconciling any of the seceded States to the government from which they have torn themselves away we cannot say,” the convention declared, “but we allow ourselves to hope that the masses in those States will in time learn that the dangers they were made to fear were greatly exaggerated, and that they will then be disposed to listen to calls of interest and patriotism, and return to the family from which they have gone out.”

In the meantime, Crittenden would also be instrumental in the effort to keep Kentucky neutral in the Civil War. He would tour the state advocating this policy, arguing that it would leave Kentucky well-placed to act as a mediator in the conflict. Kentuckians might not be able to stop the ensuing fight, but it certainly seemed a better alternative to him than active involvement in war.

A week before the Frankfort Conference on May 20, 1861, Kentucky’s governor would issue a proclamation declaring the state’s neutrality; in it, he claimed that this course would help promote peace. Such hopes obviously failed to stop the onrushing war that would rage for four years and kill hundreds of thousands of people. No one could foresee what would come, but Kentucky’s neutrality in 1861 — and the efforts of men like Crittenden and, to some extent, Robertson — stood as a monument to their different visions for the future in that moment. Those different visions informed their behavior during the conflict, and at least in the case of Kentucky, those ideas helped shape the broader contours of the Civil War.

Jesse George-Nichol is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Virginia.

Recent Comments