In the park next to my home, where I take my dog for long Saturday afternoon walks, is a Story Walk. In case you have never had the pleasure of visiting one, a Story Walk is a fun, interactive way to enjoy reading while spending time outside.

In a Story Walk, the pages from a picture book are taken apart, laminated, and then displayed along a walking path or in a garden. Lucky for me, the library adjacent to the park where I walk maintains the Story Walk religiously, changing the storybook to match the season. While my dog goes on his walk, I read.

In the spring, alongside the daffodils, I watch Eric Carle’s Very Hungry Caterpillar grow fat.

In the summer, while wearing flip-flops, I commiserate with Jabari from Jabari Jumps, as he debates whether or not he should hurtle his body into the pool from the high dive.

In the fall, inspired by Lois Ehlert’s Leaf Man, I collect crimson maple leaves and yellow birch leaves.

And in the winter, as I trudge through the snow, I listen hard for the hoot of a great horned owl, just like the girl and her father in Owl Moon.

In this particular park, the Story Walk is always composed of picture book pages. Picture books that are familiar. The kind that are listened to from the laps of parents and grandparents. The kind of picture books that feel like love.

Throughout the seasons, I began to notice something about this Story Walk: People of all ages enjoy the stories. And I began to wonder if my middle school students would enjoy a Story Walk.

I thought they would, so I set out to make one.

How To Create a Story Walk

1. First, choose a book, short story, or collection of poetry.

Make sure your selection works well in sections. For stories, pick books with fewer than 20 pages/sections. For poetry, choose three to six poems that fit a theme. Plan to have the outdoors match or complement (or at least not clash with) the piece in your Story Walk.

2. Break the piece into stops.

Divide the story or poems into stops (one page or one poem per stop). Each stop will be displayed on a sign or poster, so that students understand the order.

3. Prepare the pages or poems.

Print large, easy-to-read copies of each page or poem. Laminate them to protect them from the weather.

4. Map the route.

Choose a safe, accessible path around the school. It could be along a fence, around a playground, along the walls of the school, or maybe even throughout a nature trail. (If it is too cold, hot, or rainy outside, the Story Walk could be moved inside and take place in the hallways or in the library.)

5. Post your pages.

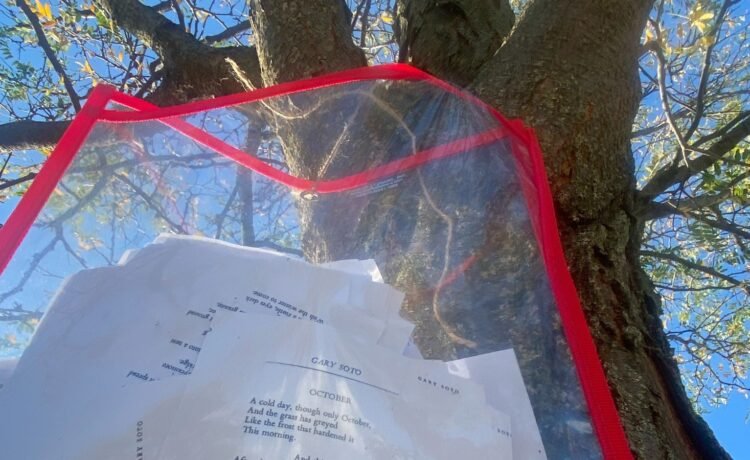

Attach each laminated page to tree limbs, fence posts, or walls using string, zip ties, or tape. Check visibility and distance. Keep them at eye level for the students. Allow for enough distance between each stop for movement and maybe even a little chatting. In fact, you could even include discussion questions about the poem or ways for students to respond with an activity.

6. Share, celebrate, and reflect.

Gather at the end and ask students to share what they most enjoyed about the Story Walk. Invite students’ families to enjoy the walk too. It could even become interactive. For example, ask students to illustrate their favorite stop (then hang up some of the best illustrations).

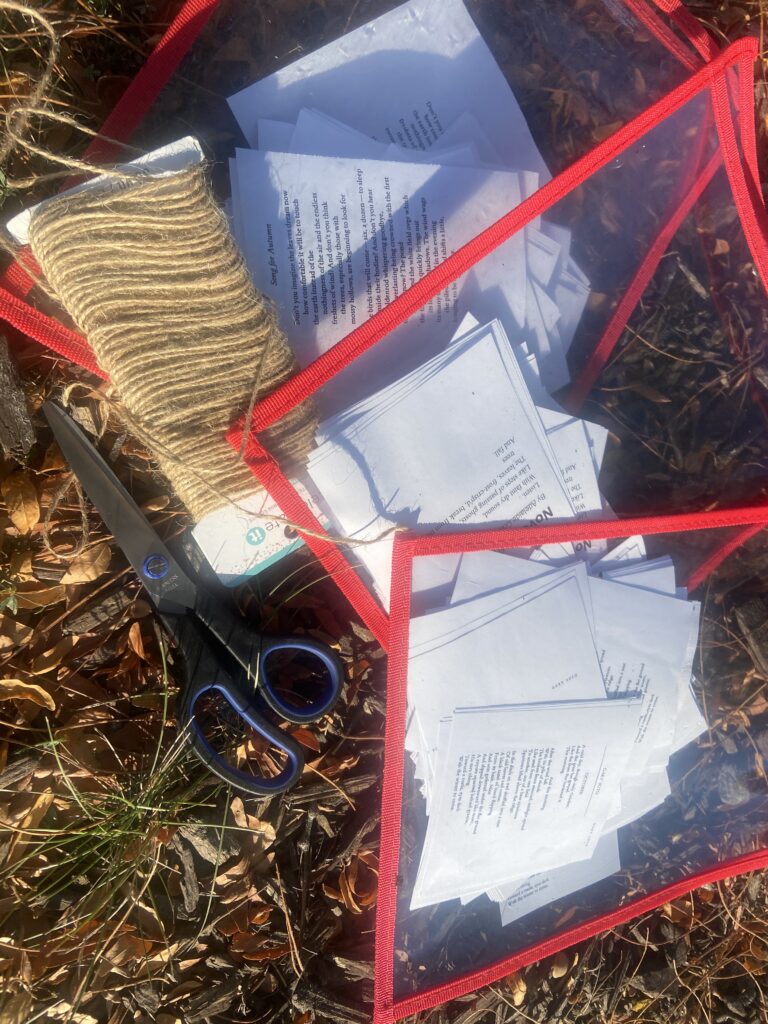

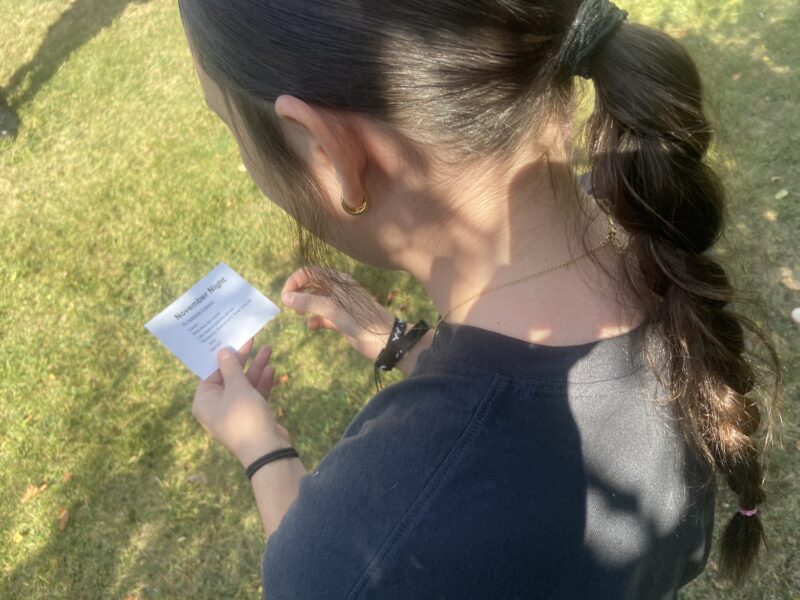

In our classroom, we have been reading poetry, so I decided to make a poetry Story Walk. I found and made miniature copies of fall-themed poems. Instead of laminating them, I pulled out my reusable dry-erase pocket folders (the kind that already have a reinforced hole at the top). Inside each of these folders, I packed enough poems so that all 130+ students would have a copy of each poem.

During my morning prep, I set out to find three stops. I found three worthy tree limbs from which to hang the poems, and I was sure to give them enough distance to make this Story Walk-turned-poetry stroll feel like we got some exercise.

Expectations for a Story Walk

It can be a very brave task to take a group of 30+ tweens and teens outside on a Story Walk. It is good to have one’s expectations in check. Here are some helpful expectations to go over with students before setting out on the walk.

1. Voices should match the setting.

For this activity, explain that inside voices will be used outside. Students should be able to hear the reader. No shouting to friends across the way.

2. Movement is part of the process.

Walking calmly to each poem is expected. Leaning against a tree while listening or reading is lovely. Stretching in the grass is A-OK. Picking up an acorn to throw at a friend’s head? Not OK.

3. Respect the space.

Talk about what being a steward of the land means. Don’t trample plants. Don’t litter (in fact, pick up litter—your own as well as that left by others). Don’t climb where you shouldn’t.

4. Focus on the senses.

How does being outside affect one’s understanding of the reading? What do the students hear, see, and feel? It might be prudent for older students to bring small notepads or clipboards to take notes.

Why a Story Walk Is a Great Idea

There is something really extraordinary about watching students step outside of the classroom and into a story. When we went outside for our Story Walk, the weather was perfect. The sun was shining, and the breeze was gentle enough to rustle the leaves above us. As we read “October” by Gary Soto, the words seemed to come alive in a new way. Suddenly, we were not just reading a poem, we were experiencing it.

As we moved from poem to poem, students took turns reading aloud about the trees, the sky, and the animals while standing right in the middle of all three. It was a bit of a miracle how a line of poetry matched the rhythm of the wind and how the sunshine made a poem feel warmer. It reminded me of something important: Learning doesn’t have to happen behind a desk. And maybe the best learning doesn’t.

Recent Comments