The Palmer Raids are generally understood by professional historians to have been unconstitutional, aggressive and abusive mass arrests and deportations of political enemies in 1919 and 1920. The raids and deportations in 36 cities, but especially in New York State, provoked a national reaction focused on protecting the human rights and civil liberties won during the American Revolution.

The Palmer Raids are generally understood by professional historians to have been unconstitutional, aggressive and abusive mass arrests and deportations of political enemies in 1919 and 1920. The raids and deportations in 36 cities, but especially in New York State, provoked a national reaction focused on protecting the human rights and civil liberties won during the American Revolution.

The Palmer Raids, in conjunction with raids conducted by New York State’s Lusk Committee, were some of the most egregious constitutional violations in the era now known disreputably as “The First Red Scare.” At the time the American understanding of the social contract was being intensely debated as part of a great international war between the haves and the have-nots.

Resistance

The power of American labor, women, and Black Americans chafed against the Gilded Age (1870s-1900) and each other. Economic disparity was at an all-time high, along with immigration. The Great Atlantic Migration was underway as Europeans, especially Southern and Eastern Europeans, fled conflict and economic hardship.

The First World War (1914-1918), the Irish Revolution (1916-23) and the Russian Revolution (1917-1923) brought more liberally-minded people to the United States, many of them having been politically suppressed Leftists in their home countries.

They were, as Emma Lazarus’s 1883 poem on the Statue of Liberty says, the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” They bolstered the America’s labor movement.

Thanks to the long struggles of unions, American workers in the first decades of 1900s had a higher standard of living than those in Europe. Skilled workers especially had higher wages, although all workers still suffered longer hours, a greater chance of being injured on the job, and fewer safety-nets than their European counterparts.

Thanks to the long struggles of unions, American workers in the first decades of 1900s had a higher standard of living than those in Europe. Skilled workers especially had higher wages, although all workers still suffered longer hours, a greater chance of being injured on the job, and fewer safety-nets than their European counterparts.

In these years a series of events introduced Americans who were not members of the two percent of households that held three-quarters of the country’s wealth to organizing to seize for themselves the fruits of their labor. Fear of their increasing power was often easily disguised as an existential threat of communism and anarchy.

The violence against workers at the Haymarket (1886), by Carnegie in Homestead (1892), and during the national Pullman Strike in 1905 helped turn American sympathies toward workers. The Industrial Workers of the World (the I.W.W., the Wobblies) was founded in 1905 to advocate for all workers, skilled or unskilled, regardless of race or gender.

When 146 workers were killed, mostly young women, at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire in 1911, the plight of American workers was laid bare.

A war in America’s coal fields led to the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which 21 people were killed, including 11 children and perpetuated a widening resistance to the use of government and corporate militias against American workers.

Americans turned to labor unions and new political parties in numbers never seen before. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) had about 50,000 members in 1886 and nearly three million by 1924. During that same time union manufacturing wages almost doubled; by 1954 almost 35% of American workers were unionized.

Americans turned to labor unions and new political parties in numbers never seen before. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) had about 50,000 members in 1886 and nearly three million by 1924. During that same time union manufacturing wages almost doubled; by 1954 almost 35% of American workers were unionized.

Red Summer

In a private conversation in March of 1919 President Woodrow Wilson, who re-segregated government, said “the American Negro returning from abroad would be our greatest medium in conveying Bolshevism to America.” Wilson had recently appointed George Edmund Haynes, the director of the National Urban League, as director of a newly established Department of Labor’s Division of Negro Economics.

In 1919, Haynes’ Division documented 38 times mobs of white supremacists attacked black people in widely scattered American cities, often over labor issues as companies hired Black strikebreakers. Between January 1 and September 14, 1919, at least 43 Black Americans were lynched; another eight were burned at the stake. The states refused to prosecute these public spectacle murders.

The Globe Malleable Iron Works in Syracuse on July 31, 1919 striking white workers attacked black strikebreakers hired by the company in an effort to end the strike. A similar riot happened about two weeks earlier in Utica.

These strikes were among the more than 3,600 involving four million workers that took place that year.

A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979), who would later found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, demanded that Black Americans had an inherent right of self-defense.

New York Anarchists

The suppression of their local labor movement led Italian organizer Luigi Galleani (1863-1931) to come to a belief in the “propaganda of the deed.” Galleani was exiled for his organizing to the island of Pantelleria, but escaped in 1901 and found his way to Patterson, New Jersey and began editing La Quesione Sociale.

During the 1902 Paterson Silk Dryers’ Strike he gave a speech calling for a general strike. When police moved-in he was shot in the face, then charged with incitement to riot. After absconding to Canada he landed in Barre, Vermont, where he launched Cronaca Sovversiva (1903-1920), one of America’s most important anarchist periodicals.

During the 1902 Paterson Silk Dryers’ Strike he gave a speech calling for a general strike. When police moved-in he was shot in the face, then charged with incitement to riot. After absconding to Canada he landed in Barre, Vermont, where he launched Cronaca Sovversiva (1903-1920), one of America’s most important anarchist periodicals.

Cronaca Sovversiva was banned from the US Mails in 1917 and the Gallaenists, as his followers (among them Sacco and Vanzettii) were known, were declared suspects in several bombings and assassination attempts of prominent anti-immigrant politicians and business leaders. It was suppressed altogether in 1918.

Among these targets was U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer (1872-1936), whose home was bombed on June 2, 1919. Carlo Valdinocci, who once edited Cronaca Sovversiva, was killed in the blast. Aside from Valdinocci, another person was killed and two injured in two waves of attacks.

Attorney General Palmer told a House Appropriations Committee meeting that “on a certain day” the radicals would “rise up and destroy the government at one fell swoop.” On June 24, 1919, Gallaeni and nine of his closest associates were deported.

During the First World War J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972) led the Justice Department War Emergency Division’s Alien Enemy Bureau. In August 1919, the 24-year-old Hoover became director of Federal Bureau of Investigation’s new General Intelligence Division, dubbed “the Radical Division,” because its purpose was its targeting political opponents.

The Radical Division began working with the Lusk Committee, raiding political enemies. Their first major assignment was the Palmer Raids. Their targets included a range of political enemies from Marcus Garvey and Emma Goldman to future US. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who Hoover called “the most dangerous man in the United States.”

The Lusk Committee

Private, Protestant political clubs like the Ku Klux Klan-linked and Justice Department established American Protective League helped launch the First Red Scare with their own efforts to root out their political enemies during the First World War under the guise of fighting foreign infiltration and sabotage.

The largest portion of the League’s activities were designed to disrupt the I.W.W., but they were renowned for their round-ups of and disruptions of their political enemies. According to one historian, League members “spotted violators of food and gasoline regulations, rounded up draft evaders in New York, disrupted Socialist meetings in Cleveland, broke strikes, [and] threatened union men with immediate induction into the army.”

Similarly, the Anti-Yellow Dog Club for youth also sought to ostracize those they declared “disloyal,” including supporting official sanctions and vigilantism. “If a man talks against the government and can’t back up what he says, he’s a ‘yellow dog’,” according to the story on which the clubs were based.

Similarly, the Anti-Yellow Dog Club for youth also sought to ostracize those they declared “disloyal,” including supporting official sanctions and vigilantism. “If a man talks against the government and can’t back up what he says, he’s a ‘yellow dog’,” according to the story on which the clubs were based.

(It was written by Oswego County, NY native, Henry Irving Dodge, a great-grand-nephew of Washington Irving who father had served in the American Revolution and the War of 1812.)

Other groups took similar approaches, including the Knights of Liberty, Sedition Slammers, Terrible Threateners, Boy Spies of America, National Security League, and American Defense Society.

Archibald Ewing Stevenson (1884-1961) was a New York attorney and professional anti-radical with a hatred of his political opponents and the connections to put that hate into action. On August 31, 1918, Stevenson and his American Protective League helped federal agents raid the headquarters of the National Civil Liberties Bureau, forerunner of the American Civil Liberties Union, in New York City.

In January 1919, Stevenson encouraged by the private Manhattan Union League Club, of which he was a member, to investigate and suppress “alien enemies.” They issued a report in March 1919 and within days the New York State Legislature created the Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities. It was chaired by conservative freshman Cortland County State Senator Clayton R. Lusk and so became known as the Lusk Committee.

For more than a year Lusk Committee agents and citizen volunteers spied on those perceived to be foreign inspired enemies of the United States, all under the local leadership of Rayme W. Finch, a former agent of Bureau of Investigation’s New York office who had also been targeted for bombing.

The Committee’s forces raided offices, went undercover to meetings, and assisted in the arrest of thousands of people. Most of the literature they seized was already being offered for sale in bookstores across New York State.

The first official Lusk Committee raid was on June 12, 1919 on the office of the newly established Russian Soviet Bureau at 110 West Fortieth street in New York City during which the Committee, with the help of the Radical Division, seized their papers and publications. The Bureau was organized to seek American recognition of the new Bolshevik government.

Then, with the help of city police, at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of June 21 they simultaneously raided the Rand School of Social Science, then the Socialist Party headquarters, and the New York City offices of the I.W.W. At the Rand School they seized birth control literature.

“In all of these places large quantities of written and printed matter of the character aforementioned were obtained, and in addition thereto much valuable information was had concerning the identity of the leaders of the radical revolutionary movement in America as well as the names and addresses of thousands of members of these various organizations, with a result that numerous indictments have been found in various counties of this State as a direct result of the information thus obtained,” the Lusk Committee later reported.

Two Finnish men, Carl Paivio and Gust Alonen, editors and publishers of Luokkataistelu were charged with criminal anarchy, tried, convicted and sentenced to four to eight years hard labor at Sing Sing Prison.

In August the Committees agents and local police raided the headquarters of the Union of Russian Workers in Manhattan. “These premises consist of an old private house in process of rather rapid decay. On the entrance or parlor floor was found a large room used as a schoolroom, containing a blackboard and crude desks and benches,” the later reported.

“Inquiry among the persons found therein disclosed the fact that many of them were led to gather in the premises on the supposition that they would there be taught both English and the reading and writing of their native tongue, Russian.”

“In the rear room, at the top floor of this building, were found the directors of this institution, and the editors of an anarchistic sheet called Khlieb y Volya, the guiding spirits of which were one Peter Bianki, Naum Stepanuk and Peter Krawchuk. Large quantities of anarchistic literature were found secreted in various portions of the premises and were seized.”

The three men were indicted by the extraordinary grand jury, charged with criminal anarchy, convicted and deported.

In November, 71 offices of the newly-formed Communist Party of America in New York City were raided, using more than 700 City Police. For maximum political and legal effect, the raid was planned on the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution.

“Those concerning whom there was not absolutely positive proof of membership in the Communist Party of America were released, and those concerning whom indubitable proof was possessed were held for the action of the grand jury, and later indicted,” the Lusk Committee reported.

Among those arrested were Benjamin Gitlow (1891-1965), a former Socialist Assemblyman from the Bronx, and James “Big Jim” Larkin, a founder of the Irish Labour Party and both the American Communist Party and Communist Labor Party of America. They were rounded-up at the New York James Connolly Socialist Club, which Larkin had helped establish on St Patrick’s Day in 1918.

Among those arrested were Benjamin Gitlow (1891-1965), a former Socialist Assemblyman from the Bronx, and James “Big Jim” Larkin, a founder of the Irish Labour Party and both the American Communist Party and Communist Labor Party of America. They were rounded-up at the New York James Connolly Socialist Club, which Larkin had helped establish on St Patrick’s Day in 1918.

The former Assemblyman and Big Jim got 5 to 10 at hard labor in Sing Sing. To discourage visitors, Larkin was moved to Clinton Prison in Dannamora sparking international protests.

He was eventually returned to Sing Sing, and later served at Great Meadow (Comstock Prison) where he was visited by Irish revolutionary Constance Markievicz. Released in 1922 he was immediately rearrested and imprisoned again, until he was granted a pardon by newly elected Governor Al Smith in January of 1923, rearrested, and deported in April.

Upstate Raids

The success in suppressing political opponents in New York City led the Committee to soon turn it’s attention upstate. Eighteen people were arrested and charged with criminal anarchy in Lusk’s own Cortland County “and the local headquarters of that organization entered and large quantities of seditious literature removed.”

On December 28, 1919, search warrants were executed and arrests made in Utica, Rochester and Buffalo; that night several other political party offices were raided. “Again,” the Committee reported “large quantities of seditious and revolutionary literature was seized under these search warrants, and formed the basis of numerous indictments found against the ringleaders of the revolutionary organizations in the cities mentioned.”

The Committee thanked the district attorneys who procured the indictments against their political enemies, including: Edward Swann, of New York County; Harry E. Lewis, of Kings County; Francis M. Martin, of Bronx County; William F. Love, of Monroe County; W. R. Lee, of Oneida County; James Tobin, of Cortland County; and Guy Moore, of Erie County.

“In the city of Rochester the headquarters of the Communist party were in a building commonly known as ‘Dynamite Hall’,” the Committee reported. Here they found a large library “containing books on anarchistic subjects” and “a number of immoral books.”

“Judging from the well-thumbed appearance of books of this character, and of anarchistic character, it seemed that this type of literature particularly appealed to the patrons of this library,” the Committee claimed.

“In this ‘Dynamite Hall’ was also found evidence of the fact that meetings had been held in public schools of the city of Rochester at which documents were circulated advising the propriety and the necessity of overthrowing organized government by force and violence, and in one instance a resolution had been passed in one of the public schools in the city of Rochester, at a meeting held by the Socialist local of that city, proposing that 10,000 copies of Nicolai Lenine’s revolutionary appeal to the working men of America be printed and circulated.”

“In this ‘Dynamite Hall’ was also found evidence of the fact that meetings had been held in public schools of the city of Rochester at which documents were circulated advising the propriety and the necessity of overthrowing organized government by force and violence, and in one instance a resolution had been passed in one of the public schools in the city of Rochester, at a meeting held by the Socialist local of that city, proposing that 10,000 copies of Nicolai Lenine’s revolutionary appeal to the working men of America be printed and circulated.”

Nicolai Lenine was Vladimir Lenin. His “A Letter to American Workingmen” urged Americans to join the international fight against capitalist excesses. It highlighted the importance of the Russian Revolution and called for solidarity against imperialism.

The message was delivered in the voice of a Russian sailor and circulated widely in the Americas. It drew parallels to the American Revolution and denounced imperialist war-making. It was influential document among American socialists and a portion of the labor movement of the time.

The Buffalo Raids

Buffalo, where New York’s strongest labor movement was based, was raided several times beginning with a June 1919 Palmer Raid which kicked off the federal effort. Three people were arrested, but free speech was not a crime and so they were released.

The raid help convince Palmer that he wouldn’t be able to prosecute leftist for their speech. Instead he worked to arrest as many as he could and deport as many as he could under the Immigration Act of 1918, which allowed the deportation of anyone considered “undesirable.”

In September 1919, the Great General Steel Strike, the largest labor walkout in US history up to that time, took place. More than half the workers at Lackawanna Steel in Buffalo walked out. Their demands were better working conditions, an eight-hour workday, and the right to collectively bargain.

From November 1919 into January 1920, Palmer, along with J. Edgar Hoover, and with the support of the Lusk Committee, organized mass arrests in raids on union halls, bookstores, and ethnic clubs. Including the upstate raids mentioned above, and another targeting Buffalo on January 2, 1920.

“Agents from this [Bureau of Investigation Buffalo Division] office, assisted by the local police and by former members of the American Protective League of this city, who donated their automobiles,” raided the homes of about 25 immigrants and then turned over to the local Immigration Authorities, six citizens were also arrested and prosecuted.

In addition to the thousands of arrests effected by the Lusk Committee, five Socialist Party members from New York City were expelled from the New York State Legislature: August Claessens, Samuel A. DeWitt, Samuel Orr, Charles Solomon, and Louis Waldman.

The Lusk Committee’s report called for a law requiring public school teachers to obtain “a special certificate certifying that they are persons of good character and that they are loyal to the institutions of the State and Nation,” by the end of 1920.

The Lusk Committee’s report called for a law requiring public school teachers to obtain “a special certificate certifying that they are persons of good character and that they are loyal to the institutions of the State and Nation,” by the end of 1920.

The Committee made a series of other recommendations to suppress political enemies and their ideas, all of which were vetoed by Governor Al Smith. When Smith left office they were passed again and signed by Republican Governor Nathan L. Miller.

When Smith was re-elected the laws were repealed in in 1923 and an attempt to prosecute the Rand School for operating a school without a license was ended.

“The safety of this government rests upon the reasoned and devoted loyalty of its people,” Smith said. “It does not need for its defense a system of intellectual tyranny, which, in the endeavor to choke error by force must of necessity crush truth as well.”

In the end, more than 6,000 people were arrested in the Lusk and Palmer Raids and nearly 600 people, including prominent leftist leaders, were deported. The only thing that finally limited the extant of the deportations was the resistance from the U.S. Department of Labor, established in 1913, which was the legal authority overseeing the process.

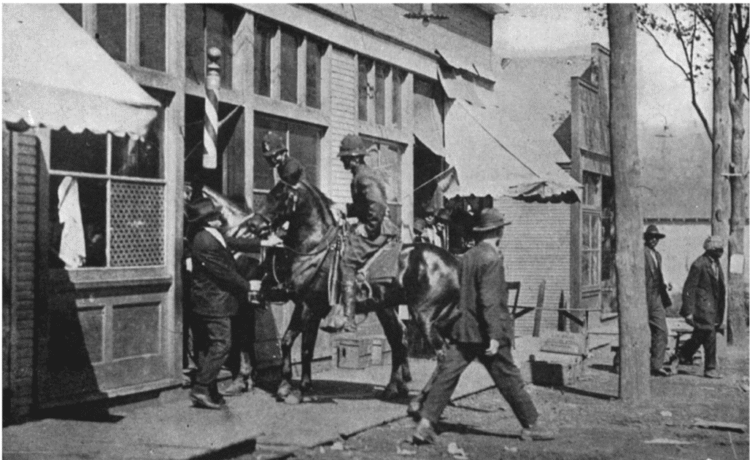

Illustrations, from above: “Pennsylvania Law and Order: State Police driving peaceful citizens out of business places, Clairton, Pa.,” during the Great Steel Strike (International Photo-Engravers’ Union of North America, IPEU, photo) from The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons by William Z. Foster; Communist Charles Ruthenberg speaking at a Market Square anti-war meeting in Cleveland, Ohio on October 28, 1917 (note the intimidating police surrounding him); Number of workers involved in US strikes each year according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (1919 strike wave in purple); Cronaca Sovversiva anarchist newspaper masthead, September 1915; Badge for members of Anti-Yellow Dog Clubs; The Lusk Committee raid on the Rand School of Social Science in August 1919; Benjamin Gitlow’s mugshot following his arrest in 1919; Lenin’s “A Letter To American Workingmen,” 1918; and the aftermath of the I.W.W. New York City headquarters after the 1919 raid.

Read more about socialism in New York State.

Recent Comments