On Monday, February 3, 1964, some 464,000 New York City school children, 45% of the city’s one million students, and over 3,000 teachers boycotted school in a protest against school segregation.

On Monday, February 3, 1964, some 464,000 New York City school children, 45% of the city’s one million students, and over 3,000 teachers boycotted school in a protest against school segregation.

Four hundred “Freedom Schools” were held at churches and other community spaces where approximately 100,000 children learned about civil rights and sang songs like the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” In 1964, over one-fourth of the city’s public school students were African American and 17 percent were Puerto Rican.

An article in the Brooklyn Eagle explained “Though segregation in New York was not codified like the Jim Crow laws in the South, a de facto segregation was evident in the city’s school system.”

As a result of housing and neighborhood segregation, 165 of the city’s 860 public schools had almost totally non‐white enrollments.

The boycott was led by the City-Wide Committee for Integrated Schools, chaired by Milton Galamison (1923-1988), pastor of Siloam Presbyterian Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Other groups involved were CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the Parents Workshop for Equality, and the Harlem Parents Committee. The Puerto Rican Association supported the boycott.

Galamison wrote a letter to New York City parents explaining “Despite the 1954 Supreme Court decision, there are more segregated schools in New York City today than there were ten years ago. Segregated schools are inferior schools — North or South… We must have pictures of people of color in readers, the Negro’s contribution to history properly presented in textbooks, Negro principals, and a representative number of Negro teachers.”

In a radio address directed at teachers, Bernard Donovan, the Deputy Superintendent of Schools, conceded that there probably would be a boycott and told the 40,000 teachers and supervisors to report for work. The Board of Education would consider “any unauthorized absence… as neglect of duty,” he said. The New York Times called the boycott “misguided.”

The Times reported picketers, made up of teachers, parents, students and activists, marched at 300 of the city’s 860 schools. The protest culminated in a march across the Brooklyn Bridge to the Board of Education building on Livingston Street in downtown Brooklyn.

Directing the boycott was long-time civil rights activist Bayard Rustin (1912-1987), who had been a chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington and had helped organize the first Freedom Ride in 1947.

A flier calling for the boycott explained:

“Many parents have wondered why the civil rights groups have called for a school boycott FEBRUARY 3rd. This is a proper attitude and one which deserves both recognition and commendation, for no parent who really has the interest of his child at heart would keep that

child out of school without sound reasons.

We have not approached our present position lightly. The fact that most of our members are parents, indeed, working parents, has weighed heavily in our deliberations. And yet, after careful study, we have indorsed the boycott and urge your full support.

Our goal is two-fold; OUR CHILDREN MUST BE GIVEN QUALITY EDUCATION IN A DE-SEGREGATED SCHOOL SYSTEM AND WE MUST KNOW WHEN THEY ARE TO BEGIN RECEIVING IT. We cannot accept any more vague promises of some sort of action sometime in the future.

We are not asking the impossible as some have claimed. We believe that every child, whether he lives in South Jamaica or Kew Gardens, is entitled to the same opportunity to develop his natural abilities.

We are not demanding indiscriminate busing. To achieve what we want there need be little more busing of children than presently exists. We do, however, feel that in a public school system, where busing is required, both Negro and white children should share the experience.

We are not calling for the destruction of the so-called neighborhood school — except where the boundaries of such a school contribute to a pattern of racial segregation.

But, why a boycott? Isn’t there any other way to force the necessary changes? Again, our reasons are two-fold.

A full-scale boycott will show, as will nothing else, how much Negro parents are willing to sacrifice for their children. The moral impact will be such that no person in authority will ever again fail to consider the determination behind our fight for equality of educational opportunities.

Our second reason is more tangible. We have found that one of the quickest ways to destroy inequality and segregation is to hit it in the pocketbook. Financial aid to the school system is based upon pupil attendance.

No pupils — no money. It’s as simple as that.

We honestly don’t want a boycott, but if the Board of Education’s plan falls short – THE DATE IS FEBRUARY 3rd.”

Read more about New York State’s Education History.

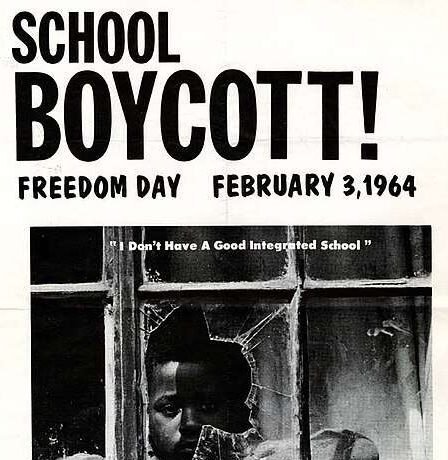

Illustrations, A flier highlights poor conditions in New York City schools and calls for a one day school boycott on February 3, 1964.

Recent Comments