Saratoga County, NY, has seen nine generations come and go in the almost 235 years since it was carved out from Albany County in 1791. Settlers moved in, established farms, mills, and small communities. Several of these communities have become villages, cities and suburban towns.

Saratoga County, NY, has seen nine generations come and go in the almost 235 years since it was carved out from Albany County in 1791. Settlers moved in, established farms, mills, and small communities. Several of these communities have become villages, cities and suburban towns.

Others have remained hamlets and become forgotten crossroads – still vibrant communities with a rich history of memories. Still others have disappeared altogether, no longer visible or remembered.

Rowland’s Hollow, also known as Rowland’s Mills, was one of those crossroads, a center of economic activity in its heyday. In 1878, Nathaniel Sylvester’s History of Saratoga County described it as follows:

“This hamlet is on the eastern line of Milton, and not far from the village of Saratoga Springs. The place is named for H.R. Rowland, the proprietor of the saw-and grist-mills that are situated upon one of the branches of the Kayderosseras.

“Southeast of the mills there are also stone-works. Prince Wing resides at Rowland’s Mills, and is very extensively engaged in milling, burning lime, and farming. In these occupations he employs a large number of persons. Prince Wing is a native of the town of Greenfield, his father having settled there at an early date.”

Sylvester gives credit to two of the most well-known entrepreneurs responsible for the development of Rowland’s Hollow. But where did they come from? And how was it that they were able to obtain the resources to develop these mills?

Sylvester hints at an important aspect of the development of Rowland’s Hollow and that is, it did not begin with these men. They were following in the footsteps of their parents and grandparents who first settled in this area years before the first dam was built to contain the first mill pond.

Isaac Rowland migrated from Pittstown, in eastern Rensselaer County with his father Oliver and brother Robert in 1802 soon after the birth of his son Hiram. Isaac began accumulating several pieces of land, beginning with the purchase at auction of property of his father, seized for non-payment of debt in 1805.

Oliver died in 1810, but son Isaac continued to add to his landholdings. Two purchases were in the 9th lot of the 16th allotment of the Kayderosseras Patent.

It was in this area that Rowland’s Mills began to take shape, midway along Rowland Street between today’s Geyser Road and Rt 29. By 1824 the mills were already in place along the creek, as Isaac parlayed his land acquisitions into successful business enterprises.

By this time Isaac had considerable influence in the community in addition to his business interests. In 1823 he became a subscriber to the newly formed Saratoga County Bank, and his involvement in banking continued – Isaac was one of the original stockholders when Ballston Spa National Bank was formed in 1839, and served as a bank director from 1840-1845.

Both his sons, Isaac and Hiram, followed their father in industrial pursuits. Isaac, Jr partnered with Chauncey Kilmer to erect a paper mill in Rock City Falls in 1840. Hiram worked alongside his father in Rowland’s Hollow, eventually taking over the family’s mills.

Three miles north of Rowland’s Mills another family had settled into the adjoining Town of Greenfield. Prince Wing – grandfather of the quarryman and mill owner- moved to Greenfield in 1786, becoming one of the first settlers in the town. He purchased property and built his home and farm on what is now Wing Road.

Grandson Prince, who was to play an important role in the development of Rowland’s Hollow, was born in 1806, and following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, continued the family’s agricultural tradition. His involvement in Rowland’s Hollow was to come later, after the mills had been operating for many years.

The death of Isaac Sr. in 1857 had a significant impact on the inhabitants of Rowland’s Hollow. He was their patriarch. The Beer’s map of 1866 gives us a good snapshot of Rowland’s Hollow as the next generation took over.

Hiram Rowland is prominently listed along with his sawmill and gristmill at the junction of the road and the creek. By this time Hiram was 70 years old, and he apparently sold this mill to Prince Wing, who one year later owned the gristmill, expanding his business interests in the Hollow where he also operated the stone quarry and lime kiln.

Wing may have been the owner, but the day-to-day operations were left to others. Joe Parmatier ran the gristmill throughout this period. He lived in the old stone house across the street from the gristmill. Patrick Leonard was the foreman for Wing’s quarry.

With all the focus on the sawmill and gristmill, it was the limestone rock itself that became the lifeblood of the Hollow in the period after the Civil War. The demand for limestone was high.

It was processed in Wing’s lime kiln and used within the Hollow itself at Isaac Wager’s plaster mill where it was ground for use by the many farms in the area. The products of the Rowland Hollow quarry were also used to construct homes, churches and commercial buildings throughout the Saratoga and Ballston area.

This vibrant community included stonecutters, millworkers, blacksmiths and lime burners whose children attended a small one room schoolhouse on the corner of Rowland Street and Grand Avenue.

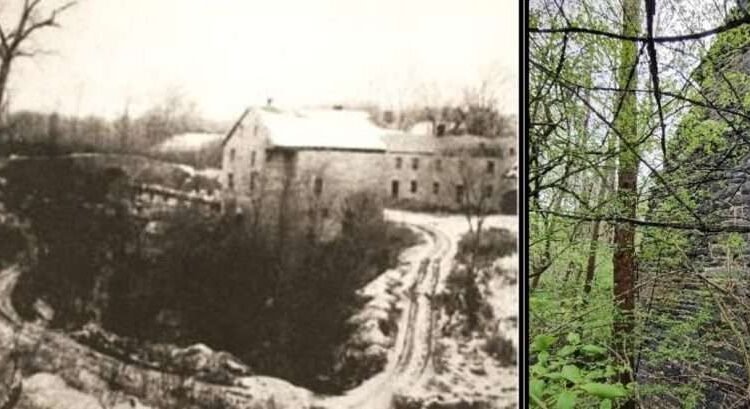

The few photos we have today from the last quarter of the 19th century show a small bustling complex of mills, homes and bridges, many constructed using the Hollow’s limestone. These images represent the second generation of Rowland’s Hollow, the first having given way as wood gives away to stone.

But this heyday was not destined to last. Soon after the turn of the century, the demand for limestone declined, as the plaster mill closed and paper manufacturers turned from straw to wood in their operations. The families that had been supported by the stonecutters and mill workers moved away, and Rowland’s Hollow was abandoned.

The limestone buildings could have, should have, lived on. But they did not. We are fortunate to have views of the Hollow as it existed in the 1930s, long after the mills had been abandoned. Even then the buildings were in ruins. Over the years since, the buildings have disappeared, the limestone repurposed for other uses in the local area.

Today it is even harder to uncover the vestiges of the Hollow. Cars and quarry trucks race along Rowland Street. If you look quick you might catch a glimpse of the northeast corner of the stone grist mill, standing 30 feet tall.

One wonders why even this remains. How many of us drive along unaware of the life that used to be in these lost crossroads?

This essay is presented by the Saratoga County History Roundtable and the Saratoga County History Center. Follow them on Facebook.

Recent Comments