Sugarbaker is a relatively common name that began to appear in American censuses from the 1830s onward. As an occupational surname, it derives from the German Zuckerbäcker. Originally, this compound noun referred to the highly rated skill of a confectioner. By the mid-nineteenth century, the word pointed at all those who worked in the sugar refining industry.

Sugarbaker is a relatively common name that began to appear in American censuses from the 1830s onward. As an occupational surname, it derives from the German Zuckerbäcker. Originally, this compound noun referred to the highly rated skill of a confectioner. By the mid-nineteenth century, the word pointed at all those who worked in the sugar refining industry.

Sugar was mega business. First produced in India, it spread to Europe by way of Persia. Venetians played a crucial role as intermediates. A hub of commerce between Europe and the East, its merchants dominated the trade until around 1500 when other regions became involved. The “mystery” skill of sugar refining was brought to America by various groups of European immigrants.

Sugar Cities

The Welser dynasty of merchants and bankers was based in Augsburg, Bavaria. Charles V (1500-1558) granted the family privileges after the conquests of the Americas as reward for support to his election as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519.

Its members established a commercial network with the Spanish colonies in South America and contributed to the formation of the transatlantic slave trade. They also owned cane plantations on the Canary Islands. The first sugar refinery in the German-speaking territories was established in Augsburg in 1573.

By the late sixteenth century, Antwerp had developed into Europe’s dominant sugar center due to its strategic trade routes to the Canary Islands and Brazil. The city’s refineries processed imported cane for re-export. After Spanish troops occupied the city in 1585, Protestant refugees fled northwards. Amsterdam benefited from Flemish expertise in a variety of professions, including sugar refining.

During the first half of the seventeenth century cane was imported from plantations in Brazil. In 1637, Haarlem-born painter Frans Post traveled there in the entourage of Governor Johan Maurits (1604-1679).

During the first half of the seventeenth century cane was imported from plantations in Brazil. In 1637, Haarlem-born painter Frans Post traveled there in the entourage of Governor Johan Maurits (1604-1679).

He became renowned for his detailed depictions of plantations and sugar mills that were carefully cleansed of the harsh realities of slave labor. When the Dutch West India Company (WIC) lost control over the region in 1654, the colony of Surinam became its leading cane supplier.

Slave labor made sugar a profitable business (“white gold”). With at least fifty refineries active in and around Amsterdam, the Dutch Republic provided most of Europe’s sugar. The growing popularity of tea and coffee caused a surge in demand. The white stuff contributed to the city’s prosperity.

Rembrandt’s pendant portraits of Maerten Soolmans and his bride Oopjen Coppit (1634) are linked to the trade. The sitter’s father Jan Soolmans was a refugee from Antwerp who owned a refinery named Vagevuur (Purgatory), a reference to the hellish heat generated during the refining process.

Amsterdam’s dominance did not last. The Republic’s decline was epitomized by the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. Its outcome was an economic disaster which was all the more painful since the conflict was caused by financiers who pocketed profits by supporting the rebellious American colonies.

The West India Company (WIC) was abolished in 1791; the East India Company (VOC) went bankrupt seven years later. Amsterdam lost its edge. Its industry withered. Sugar production moved to London.

Tate’s Sugar Cubes

During the first decade of the eighteenth century London experienced an influx of Lutheran refugees from the Electorate of the Palatinate on the Rhine River. The “Poor Palatines” gathered in Greenwich and Lewisham where they were herded into miserable encampments. Some continued their journey to the American colonies, but most of them settled in London. By 1709, some 15,000 displaced persons camped in the capital.

The migrants became involved in London’s refining industry, helped by the presence of German-speaking workers already employed there. At the outset, sugar refining took place around Upper Thames Street and St Paul’s Cathedral.

Raw sugar was shipped from the Caribbean and Brazil in large wooden barrels (hogsheads), unloaded at the wharves along the Thames, and taken to nearby sugar houses. The process was a fire hazard as syrups often caught fire. Over time, the industry moved to London’s East End as fire regulations stipulated that sugar houses had to relocate to the outskirts.

With the ascension to the throne of George I in 1714, the industry grew quickly. Migrants who followed him from the Kingdom of Hanover were employed in London’s refineries.

In 1763, St George’s (German) Lutheran Church in Little Alie Street, Aldgate, opened its doors. Its founder was Dietrich Beckmann, a wealthy sugar refiner. Two years later an Anglo-German school was established. The area became known as “Little Germany.”

In January 1843, Czech industrialist Jakob Christoph Rad patented his invention of the sugar cube. Its mass production technique was enhanced by the German engineer Carl Eugen Langen who, in 1872, sold his secret to Henry Tate. The latter had started his career as a grocer in Liverpool, establishing his first sugar refinery in 1852.

For his contemporaries, Tate became the magnate of British sugar; his name being synonymous with sugar cubes. In 1877, he opened a state of the art refinery in Silvertown, East London, which has been in operation ever since.

For his contemporaries, Tate became the magnate of British sugar; his name being synonymous with sugar cubes. In 1877, he opened a state of the art refinery in Silvertown, East London, which has been in operation ever since.

British “sugar barons” wielded considerable political sway. Henry Tate and Abram Lyle (the two firms merged in 1921 into Tate & Lyle) operated a system resembling the former slavery concept that was labeled with the metaphor “labor as commodity.” It created a legal framework that justified the exploitation of workers and limited their rights to organize. Profits were phenomenal.

Tate used his private wealth to collect British paintings with a passion for the work of Pre-Raphaelite artists. He provided funding for the construction of a museum on the site of the former Millbank Penitentiary.

Opened in 1897, it would (eventually) be named Tate Britain. His donation of sixty-five paintings and sculptures constituted the gallery’s founding collection. Tate was art’s sugar daddy.

Sweet Independence

Columbus introduced sugar cane to the Americas. On his second voyage in 1493, he brought cuttings from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola where they thrived. Sugar mills were established in Cuba by the 1520s, whilst the Portuguese began cultivating cane in Brazil, subsequently exploited by the Dutch colonial regime. Sugar prompted the Atlantic triangular trade between West Africa, the Caribbean and Europe.

In 1720, German settlers were recruited by the French colonial regime to an area along the Mississippi named les Allemands (the Germans). Roughly four hundred and fifty families made the voyage, most of them Lutherans or Calvinists who originated from the Rhineland region and Swiss cantons. They turned Louisiana’s “German Coast” into the nation’s richest cultivated region.

In 1720, German settlers were recruited by the French colonial regime to an area along the Mississippi named les Allemands (the Germans). Roughly four hundred and fifty families made the voyage, most of them Lutherans or Calvinists who originated from the Rhineland region and Swiss cantons. They turned Louisiana’s “German Coast” into the nation’s richest cultivated region.

In 1795, on a French Creole plantation near New Orleans, Étienne de Boré and Antoine Morin were the first to demonstrate that sugar cane could be profitably grown locally. The German Coast saw a steep rise its cultivation, transforming the economic prospects of local plantations. Driven by a ruthless use of African slaves, Louisiana produced most of the sugar consumed in America. The boom lasted until the Civil War which left the region’s production in shambles.

German migrants partook in sugar refining in other parts of America too. On September 18, 1727, a ship named William and Sarah under command of Captain William Hill arrived from Rotterdam at the port of Philadelphia. Those on board were recorded as “Palatine Passengers.” They probably emigrated as a group and were required to sign an Oath of Allegiance.

One of those arrivals was Alsace-born Johannes Friedrich Hilligass (or Hillegass) who had fled to the Palatinate region to escape Huguenot persecution. Michael Hillegas was a descendant of the family. A sugar refiner in Philadelphia, he promoted the Revolutionary cause.

In 1781 he was requested to edit documents relating to the nation’s foundation, including the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. He would become the first Treasurer of the new United States.

The Declaration itself needed to be communicated to all newcomers. Four days after its signing, a German version of the printed broadside was published in Philadelphia by Heinrich Miller in his newspaper Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (the only extant copy in America is held at Gettysburg College). Independence tasted sweet.

The Declaration itself needed to be communicated to all newcomers. Four days after its signing, a German version of the printed broadside was published in Philadelphia by Heinrich Miller in his newspaper Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (the only extant copy in America is held at Gettysburg College). Independence tasted sweet.

New York’s Sugar Kings

From the outset of colonization, Flemish and Dutch settlers brought their refining expertise to New Netherland. Their participation helped establish New Amsterdam as a major processing hub. Manhattan’s sugar trade was dominated by prominent settlers from the Low Countries such as the Cuyler, Roosevelt and Van Cortlandt families. Sugar created a new aristocracy.

On August 10, 1730, the New York Gazette carried an advertisement announcing the opening of a refinery on Liberty Street: “Public Notice is hereby given that Nicholas Bayard of the City of New York has erected a Refinery House for Refining all sorts of Sugar and Sugar-Candy, and has procured from Europe an experienced artist in that Mystery.”

Bayard’s forebears were French Huguenots who had sought refuge in the Dutch Republic. The first family member to arrive in colonial New York was his namesake Nicholas Bayard, a nephew of Peter Stuyvesant who acted as his patron. A merchant and slave trader, he served as the 16th Mayor of New York in 1685/6.

Demand for sugar fueled the foundation of refineries in Lower Manhattan. With Louisiana’s cane cultivation at a standstill, imports from Cuba were crucial. The island stopped participating in the slave trade in 1867, but the institution of slavery lasted there until 1886.

Over a period of three centuries, some half a million workers were transported to its plantations. Cuba enabled the rise of the city of New York’s refineries. The Hudson River Valley provided a strategic location for cane to be granulated, packaged and transported. A railway system developed during the 1840s had accelerated the arrival of heavy industry in the area (including the dolomite marble quarries).

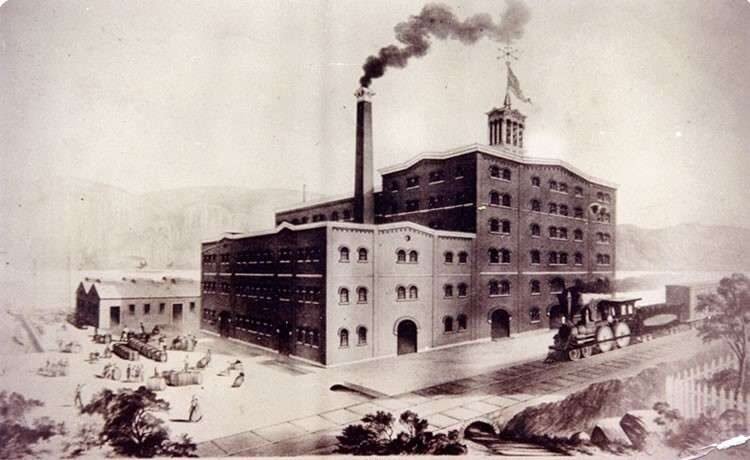

In 1853, two German immigrants named Kattenhorn and Hopke built a factory at Hastings-on-Hudson, calling it the Hudson River Steam Sugar Refinery. Its workforce consisted mostly of migrants who had escaped the failed German revolutions.

In 1853, two German immigrants named Kattenhorn and Hopke built a factory at Hastings-on-Hudson, calling it the Hudson River Steam Sugar Refinery. Its workforce consisted mostly of migrants who had escaped the failed German revolutions.

Utilizing the latest steam power technology, the refinery remained in operation until a fire destroyed the factory on Christmas Eve in 1875. Many of the workers left Hastings to seek employment in Brooklyn.

Going back to the first half of the seventeenth century, the Havemeyer (Hoevemeyer) dynasty descended from Bückeburg in the principality of Schaumburg-Lippe, Lower Saxony, where a number of its members had been bakers and confectioners. Schaumburg, Illinois, was founded by settlers from the region.

Aged fifteen, Wilhelm [William] Havemeyer moved to London in 1785 to train as a sugar baker. In 1799, he sailed to New York to take charge of Edmund Seaman’s sugar house on Pine Street, Lower Manhattan. His younger brother Frederick Christian followed a few years later. In 1805 the brothers leased land from Trinity Church on Budd Street (later renamed Vandam Street) to build their own sugar bakery which opened in 1807.

The Havemeyer brothers retired in 1828. Their respective sons, cousins William Frederick and Frederick Christian Jr. continued the business. The former left the firm in 1842 to embark on a political career, serving three terms as Democrat Mayor of New York City (1845/6; 1848/9 and 1873/4).

In spite of various changes, the company remained in control of the family. During the late 1850s a decision was made to move the refinery to Williamsburg, an industrial hub on the waterfront that had recently been incorporated into Brooklyn.

The firm benefited from mass immigration during that era, employing Polish newcomers who worked for starvation wages. On retirement, Frederick left the running of the business to his sons Theodore and Henry Osborne.

In 1887, they organized the American Sugar Refineries Company (known as the “Sugar Trust”), an oligopoly of nine local and eleven refineries nationwide that controlled the market. Because of legal wrangling about business practices, the brothers dissolved the Trust in 1891 and incorporated as the American Sugar Refining Company.

Dominating the waterfront, it controlled the nation’s sugar supply – Williamsburg was nicknamed “Havemeyer Town.”

Bittersweet Legacies

Theodore Havemeyer is remembered today as the first President of the U.S. Golf Association and as co-founder of the Newport Country Club, host to both the first Amateur Championship and the first U.S. Open in 1895. Henry Osborne spent his wealth on the acquisition of antiquities and works of art.

A keen amateur violinist, he practiced daily on a 1708 Stradivarius, now referred to as the “Havemeyer.” Henry caught the collecting fever in 1876 during his visit to the “International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine” (better known as the Centennial Exhibition) in Philadelphia where he purchased a range of treasures to adorn his mansion at 1 East 66th Street (with interior designs by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Samuel Colman).

He and his wife Louisine assembled an extraordinary collection of Old Masters and Impressionist painters. The latter was friends with artist Mary Cassatt who, living in France, was close to many French painters at the time and acted as an advisor to the family (Louisine was the first American collector to buy a work by Claude Monet).

He and his wife Louisine assembled an extraordinary collection of Old Masters and Impressionist painters. The latter was friends with artist Mary Cassatt who, living in France, was close to many French painters at the time and acted as an advisor to the family (Louisine was the first American collector to buy a work by Claude Monet).

On her death in January 1929, she bequeathed many paintings to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Part of the collection was inherited by her daughter Electra Havemeyer Webb. Founder of the Shelburne Museum, Vermont, these works are now part of its permanent collection.

Henry Tate and Henry Osborne Havemeyer were sugar bakers who maintained a business model that was rooted in colonial slavery by exploiting a workforce consisting of poorly paid immigrants laboring under harsh conditions.

Their legacy? Grand museums; splendid collections; ugly histories.

Read more about New York’s sugar industry.

Illustrations, from above: Coat of arms of the confectioners, Lebzelts and Schokolademaker by Hugo Ströhl (1904-1910); Frans Post, Sugar cane mill in Brazil, undated, mid-seventeenth century (Louvre); Tate and Lyle sugar promotional advertisement; Map of “German Coast” of Louisiana, 1775; Lithograph of the Kattenhorn & Hopke sugar refinery in 1860; and Mary Cassatt, Portrait of Louisine Havermeyer, 1896 (Shelburne Museum).

Recent Comments