The Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) made Lake George more accessible than any other resort area in the Northeast. So, it’s appropriate that the birth of the modern interstate highway system can be traced to Lake George; specifically, to the 46th Annual National Governor’s Conference, held July 11 to 13, 1954, at the Sagamore Hotel in Bolton Landing.

The Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) made Lake George more accessible than any other resort area in the Northeast. So, it’s appropriate that the birth of the modern interstate highway system can be traced to Lake George; specifically, to the 46th Annual National Governor’s Conference, held July 11 to 13, 1954, at the Sagamore Hotel in Bolton Landing.

To be precise, the Conference was the site not so much of the birth of the interstate highway system, but of the announcement of its birth.

President Dwight Eisenhower was slated to be the conference’s keynote speaker, and as late as two days before its start, the Lake George Mirror was anticipating his arrival, publishing the presidential photo on the cover, noting, hopefully, that the President might not only fly in Monday night but stay at the Sagamore overnight.

Because of the death of a sister-in-law, Eisenhower was forced to cancel his appearance and Vice-President Richard Nixon attended in his place, delivering the President’s remarks. It was assumed that he would speak in a general way about world affairs. The speech Eisenhower planned to deliver was a far more significant one.

Through his Vice-President, Eisenhower stated, (according to the Lake George Mirror) “the federal government should take the lead in planning and building a modern highway system.”

The conference was not, of course, limited to discussions of policy. The Bolton Central School Band played for Nixon in front of the hotel’s lakeside porches.

The conference was not, of course, limited to discussions of policy. The Bolton Central School Band played for Nixon in front of the hotel’s lakeside porches.

Sidney Rossoff of Merkel and Gelman conducted a fashion show. Actor George Murphy, who would later become a U.S. Senator from California, flew in from Hollywood to be the Master of Ceremonies for the nightly entertainment. Murphy was a former four-star general who had known President Eisenhower in the army.

Connecticut Governor John Lodge (another actor turned politician) and his family went fishing with former Bolton Supervisor Frank Dagles in one of F.R. Smith’s electric boats. According to the Lake George Mirror, “Governor Lodge landed a five-and-a-half-pound trout. It was noteworthy that Mrs. Lodge and the girls all wore identical leopard skin bathing suits. And all three were dressed alike at the women’s fashion show.”

Planning the Interstate Highway System

Moved to act by Nixon’s address, the Governors appointed a committee to look at the current, inadequate conditions of state highways. In September of that year, Eisenhower appointed a committee led by General Lucius Clay to make a study of a federally funded interstate highway system.

“It was very evident that we needed better highways,” Clay recalled. “We needed them to accommodate more automobiles safely. We needed them for defense purposes, should that ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy.”

(It was also assumed that a public works project of that scale might forestall a recession.)

Two years after Nixon’s speech at the Sagamore, Congress passed the Federal Interstate Highway Act, which committed Washington to paying 90% of the costs of a national system of superhighways. It remains the largest federal public works project in the nation’s history.

A Personal Reflection

When my parents came to the Adirondacks in 1956, they believed they were moving to a place far removed – culturally and politically as well as geographically – from the cities in which they had worked as left-wing journalists.

Beyond the Adirondacks lay “the big world,” as our neighbor Peggy Hamilton called it. (It was a world she was familiar with, having been the companion of Vida Mulholland and, like Vida and her more famous sister Inez, an early advocate of women’s rights.)

The 175-mile-long Northway between Albany and Montreal, which Governor Nelson Rockefeller officially declared completed ten years later, brought that “big world” that much closer.

For practical as well as political reasons, the last stretch to be completed was the piece between Ausable Chasm and Lake George, an accomplishment possible only after the passage of a constitutional referendum allowing the condemnation of 254 acres of Forest Preserve.

For practical as well as political reasons, the last stretch to be completed was the piece between Ausable Chasm and Lake George, an accomplishment possible only after the passage of a constitutional referendum allowing the condemnation of 254 acres of Forest Preserve.

As a newspaper editor, my father supported the constitutional amendment, arguing “We need trunk line highways connecting our communities with the great population areas to the north and south.”

The Lake George Mirror also supported the amendment, and for similar reasons, commenting in 1957, “one thing on which all business leaders are agreed upon… is the importance of the Northway to the economy of the entire area. The extreme competition between recreational areas in several adjoining states which have become readily accessible to metropolitan areas through construction of express highways, are diverting vacation and tourist trade away from the Lake George-Adirondack region.”

The amendment passed by 400,000 votes state-wide and by far larger margins in Essex and Warren Counties. Having made certain the highway passed through the Adirondack Park, local officials sought to extract the maximum amount of publicity for the region, including having the road named “the Adirondack Northway.

That was not as easy as it sounds, however. Since the highway is a federal one and federal highways receive no designations beyond the numbers attached to them, the Northway’s official name was, and remains, I-87.

Thanks to our late Assemblyman Dick Bartlett, though, travelers on highways over which the federal government has no jurisdiction and which happen to intersect with the interstate are directed to “the Adirondack Northway.”

America’s Most Scenic Highway

As of Independence Day, 1963, the Northway stretched from Albany to what is now Exit 20, 3.5 miles south of Lake George. “The timely opening of the expressway expedited the mass movement of motorists to the north for the holiday weekend,” the Lake George Mirror reported, adding that business owners were reporting a 50% increase in trade over the previous year.

“Every form of ‘night spot’ have reported that never have so many automobiles been parked at their places heretofore.”

In 1964, the Mirror was able to report that plans for the Lake George by-pass included the rest area and overlook on the foothill of Prospect Mountain. “It may inure to the benefit of the village because travelers, on seeing this lovely village on the lake below them, may choose to stay over.”

In 1964, the Mirror was able to report that plans for the Lake George by-pass included the rest area and overlook on the foothill of Prospect Mountain. “It may inure to the benefit of the village because travelers, on seeing this lovely village on the lake below them, may choose to stay over.”

Construction of the entire Northway was completed in 1967. In March of that year, Parade magazine (a weekly supplement to Hearst newspapers) announced that a 23-mile stretch of the highway, from Lake George to Pottersville, was that year’s winner of its Scenic Highway Award. “The award…. designates the new highway which best embodies the principles of good design, beauty and utility,” the magazine stated.

The Northway between Lake George and Pottersville, the magazine added, “traverses the Adirondack Park and takes full advantage of the area’s natural beauty through the utilization of fine design concepts.”

Civilization and its Discontents

Roger Tubby, the publisher of the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, had led the committee organized to secure passage of the constitutional amendment permitting the Northway to cross the Forest Preserve.

Tubby, who had been President Harry Truman’s press secretary, my parents and many of their mutual friends were part of a generation whose attitudes had been shaped by the urban experience but who chose to make lives in the country.

Their stories were captured and at least to some extent, perhaps, inspired by many books published in the 1940s and 50s, including Granville Hicks’ Small Town, Henry Beetle Hough’s Country Editor, Henry Beston’s Northern Farm and Helen and Scott Nearing’s Living the Good Life. Eric Hodgins’ Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House was the comic equivalent of those books.

I’ve often wondered if people like my father, Roger Tubby and Dick Lawrence, a former New Yorker who was the Adirondack Park Agency’s first chairman, were troubled by the tension between their pursuit of a rural life on the one hand and their support for the Northway on the other.

The Northway certainly brought tourists and second-home buyers to Lake George and the Adirondacks. But it by-passed the roadside motels, gas stations, souvenir shops and the small, family-owned theme parks. It can be blamed for eviscerating the Main Street economies of towns like Warrensburg and Elizabethtown, encouraging travelers to hurry past them and the residents to do their shopping at the plazas being constructed on the margins of Glens Falls and Plattsburgh.

(Prior to the construction of the Northway, a visit to one of those cities merited a mention in the columns of the weekly newspaper.)

Three Cheers for the Northway? How about Two?

Whatever its impact on Main Street, the Northway can be credited for increasing the size of a constituency supporting the protection of the Adirondacks, one that included those who now had access to the largest wilderness in the northeast.

In 1959, the year the constitutional amendment was approved, a group of conservationists, publisher Alfred A. Knopf and former conservation commissioner Lithgow Osborne among them, purchased a full-page ad in The New York Times in support of it, arguing that the best way to protect the Forest Preserve was to give people an opportunity to see at least a portion of it up close and for themselves.

Even those who favored the construction of the Northway, however, knew that its legacy would be an ambiguous one, which is one reason why Governor Nelson Rockefeller appointed his Temporary Study Commission on the Future of the Adirondack Park only one year after the highway was completed.

With the Adirondack Park more widely known and more accessible than ever, it was also likely to become more vulnerable to over-development than ever. Even before it was completed, conservationists warned that the new highway, when added to increasing demands for second homes and recreational opportunities, would place an unprecedented stress upon the Adirondacks.

By 1969, even the business-friendly Lake George Mirror was complaining, “We are faced with problems caused by growth.” As more people acquired more leisure time, and more time to spend on Lake George, there were “more cars, more highways, more people who own or rent boats, more people who require more tourist accommodations and more people to staff the cottages, motels, restaurants and stores.”

Rockefeller’s Temporary Study Commission developed recommendations to protect the Adirondack Park, most notably, the creation of a regional Adirondack Park Agency (APA) regulating both public and private lands within the park.

I find it interesting that the commission included Lawrence, my father and Roger Tubby’s partner at the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, Jim Loeb; and that the founders of the Adirondack Nature Conservancy included people like Wayne Byrne, a Yale Forestry School graduate who had taken over his wife’s family’s hardware business in Plattsburgh.

Perhaps because they chose to relocate themselves to the country, they were more keenly aware of its value than others may have been.

It can be argued that the Northway destroyed whatever space remained between the cities that people like my parents had fled and the refuge they sought in the Adirondacks. To do so, however, is to overlook the fact that the country, as an intellectual construct at least, had been undermined long before the Northway was completed.

No doubt, by the 1950s, many of these ex-urbanities had come to realize that there was little or no escape from mass culture or consumer-oriented shopping centers.

But it was books like Rachael Carson’s Silent Spring, ostensibly about a rather dull topic, a pesticide, DDT, that seems to have forced even the most obstinate to acknowledge that a distinction between city and country was no longer viable.

You could no more escape modern civilization and its discontents than you could hide from the pervasive effects of pesticides and, for that matter, air pollution and the fallout from nuclear weapons testing.

More than fifty years after the completion of the Northway, we still live with its consequences, both good and ill: a wealthier economy but one less self-sufficient and one increasingly dependent upon tourists and second homeowners; a protected Adirondack Park, but sometimes a crowded one, so much so that every so often New York State considers introducing limits to the numbers who can hike the High Peaks on any given day.

Read more about I-87, the Adirondack Northway.

A version of this article first appeared on the Lake George Mirror, America’s oldest resort paper, covering Lake George and its surrounding environs. You can subscribe to the Mirror HERE.

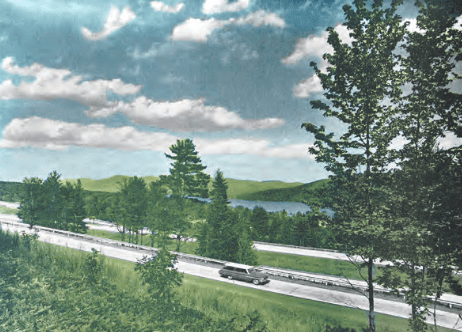

Illustrations, from above: the Northway above Lake George, as portrayed by the Lake George Mirror; I-87 Adirondack Northway Alternative Routes Map, 1957; Governor Nelson Rockefeller announces the completion of the Northway at a 1967 press conference; and the Northway below Prospect Mountain at Lake George.

Recent Comments