Into the waning decade of the 1700s, only fords, ferries, or makeshift timber bridges, all highly vulnerable to frequent destruction by ice and flood, were used to cross streams. As Americans in greater numbers began moving west to more remote parts of New York and Pennsylvania, carpenters and entrepreneurial inventors began envisioning new designs but still using posts, beams, and trestle bents for crossing narrow and slow-moving streams in order to expedite the movement of people and goods as well as to make a profit. None of these earliest timber bridges were covered with a roof and siding.

Into the waning decade of the 1700s, only fords, ferries, or makeshift timber bridges, all highly vulnerable to frequent destruction by ice and flood, were used to cross streams. As Americans in greater numbers began moving west to more remote parts of New York and Pennsylvania, carpenters and entrepreneurial inventors began envisioning new designs but still using posts, beams, and trestle bents for crossing narrow and slow-moving streams in order to expedite the movement of people and goods as well as to make a profit. None of these earliest timber bridges were covered with a roof and siding.

These early timber bridges were precursor structures to the arches and trusses that soon followed, making it possible to span broader streams with stronger structures, many of which heralded the arrival of the covered timber bridge era.

Throughout this prolonged period of innovation carried on by untrained builders, New York State remained a formidable proving ground in the evolution of timber bridge building.

Traditional beam bridges were relatively simple structures, comprised of parallel timbers called stringers that supported the deck or roadway above. The crossings typically employed readily available tree trunks laid side-by-side and held up by posts sunk into the stream bed.

Pairs of posts could be improved by being replaced with trestle structures with a structural support called a bent. Bents are comprised of vertical posts with several horizontal sills as well as angled braces.

Pairs of posts could be improved by being replaced with trestle structures with a structural support called a bent. Bents are comprised of vertical posts with several horizontal sills as well as angled braces.

Wooden bents could be assembled on land, then when conditions were suitable pounded into the mud of the river bed at appropriate spacing as the substructure for the bridge deck. Trial and error governed the possibility of success.

Whether supported by a series of posts or more substantial trestle bents, low-lying beam bridges, while practical, had several common disadvantages: span was limited by the length and species of available tree trunks. Moreover, timber beams were prone to sag as they naturally aged or were weakened because of excessive loads passing over them.

As early newspapers frequently reported, the effects of weather, especially the passage of seasonal ice floes and floods, usually called freshets in the past, regularly swept away portions or all of these types of bridge bringing inconvenience to locals by disrupting travel. Fortunately, after timber components were swept away, they sometimes could be salvaged and the crossing restored.

Well before the celebrated Theodore Burr began his New York bridge building career in 1800 with a pair of modest beam bridges serving local needs, one in his adopted hometown of Oxford over the Chenango River and another at the Esperance crossing of Schoharie Creek, an extraordinarily long bridge — more than one mile in length — was erected across Cayuga Lake in Central New York.

Essentially forgotten, this impressive structure deserves a new look.

The Cayuga Long Bridge, which is also known as the Cayuga Lake Bridge, was an exceptional example of a great bridge at the very beginning of the nineteenth century that was unrivaled in the United States at the time.

Located in today’s Seneca County in an area that had been a part of the larger Onondaga County and after 1799 Cayuga County, the bridge was at a site less than ninety miles from Theodore Burr’s home at Oxford. Whether Burr knew of this exceptional bridge is conjectural.

At nearly 40 miles from north to south, Cayuga Lake is the longest and has the second largest surface area of central New York’s Finger Lakes.

With an average width of 1.7 miles (2.8 km), and maximum width of 3.5 miles, the lake was an impediment to migrant travelers traversing the Great Genessee Road, a critical conduit westward into central and western New York State.

By the later part of the eighteenth century, it was generally understood that only a well-placed bridge, instead of a ferry, could ease the passage of migrants and goods across the water body.

By the later part of the eighteenth century, it was generally understood that only a well-placed bridge, instead of a ferry, could ease the passage of migrants and goods across the water body.

The State Legislature authorized the formation of the Cayuga Bridge Company on March 28, 1797, with an announcement that was posted in many newspapers throughout the state.

Thus, it is possible that Theodore Burr could have known about this planned structure, and possibly even visited what was acknowledged as a unique and grand bridge. The Cayuga Lake Bridge was begun in 1799 with subscriptions totaling $25,000 capitalization that was raised by the Cayuga Bridge Company.

Hopefully, profits for subscribers were to be gained from tolls that ranged from $1 for a 4-wheel carriage and horse to twenty-five cents for a horse and rider, to two cents for every sheep or hog:

After 18 months of construction by the Manhattan Company of New York, the bridge was passable in September 1800. With a length of 5,412 feet and at twenty-two feet wide, it was broad enough for carriages, stagecoaches, carts, and wagons to pass in both directions. There is no image of the original 1800 crossing

One of the earliest travelers to glimpse the bridge from a ferry was John Maude who reported with a remarkable level of detail in a nearly 400-page diary on his visit on July 7, 1800 while traveling to “the falls of Niagara”:

“Harris’s Tavern; one hundred and eighty-six miles [since beginning the journey] Finding that there were no Oats to be had, that the Hay was half a mile from the stable, and that Mrs. H. had no eggs to her bacon, I ordered my horses to the ferry, first giving them a little rest and grass.

“Cayuga; has risen from the woods since two years, contains fourteen houses inhabited, though not all finished, and fourteen building; amongst these, one on the top of the Hill, first intended for an Inn, now designed for a Court-house. This town is not very healthy: the body of water is to the S.W. the worst possible aspect.

“2 P. M. Embarked in the ferry-boat; made sail with wind on starboard bow, to wit, a North-wester; obliged to tack for fear of running foul [sic] of the New Bridge; This Bridge; will be a mile and quarter in length; the longest in America-perhaps in the world! Yet five years ago the Indians possessed the shores of this Lake, embosomed in almost impenetrable woods!

“The breadth of the Bridge is twenty two feet within the railings; the bends [sic] are twenty-five feet apart; the Bridge is more than three parts finished was begun fourteen

months ago, and is supposed to be passable in four months more: the cost is estimated at thirty thousand dollars.

“The Proprietors are some adventurous spirits in New York; in a few years they will receive cent per cent for their money. In February last, from fifty to one hundred teams passed this ferry in a day, and upwards often thousand bushels of wheat in a week.

“The Lake at the Ferry has six, eight, and twelve feet of water, and twenty feet of mud and soft ground the water is so clear, that I could see the bottom the whole passage; is forty miles long and four at the widest, where the water has not yet been fathomed, and never freezes:

“both ends of the lake freeze sufficiently strong to admit the passage of waggons and sleighs on the ice; well stocked with fish, as Bass, (this is a favorite word with the Americans; they not only call trees of this name, but five or six distinct kinds of fish), Cat-fish, Eels, Pickerel, etc., etc. Catfish have been taken thirty pounds and upward, reckoned the finest fish in the Lake.”

The well-traveled Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College, crossed over the bridge in October, 1804, also on his way to Niagara, declaring “The bridge over this lake, considering the recency of the settlements, may be justly styled a stupendous erection: and is probably the longest work of its kind in the United States . . . It is built on wooden trestles, in the plainest and most ordinary manner. . . The toll is a quarter of a dollar for man and horse; the highest, I believe, in the United States; if we consider the amount the capital, and the quantum of travelling.”

Though quickly popular even with high tolls for vehicles and animals, severe winter conditions in the ensuing years led to eventual collapse.

Various possible dates between 1806 and 1809 are reported by John Wells for the loss of the bridge to ice, but he concludes confidently that the 1876 History of Seneca Co., New York is correct that the loss came in the winter of 1808 because of both “defective construction” and ice:

“the bends [sic] were separately framed, properly placed, and held in position by stringers which were notched on the caps, and those outside bolted down. Some of the bends began to settle and lean to the west, and in 1808 the whole mass gave way. The plank, railing, and stringers floated off down to the marsh at the foot of the lake. The bends were to be seen years afterwards lying in order on the bottom.”

With the loss of the bridge as winter ended, the State Legislature on April 6, 1808 authorized a ferry “where the former bridge stood” forcing travelers to endure the unpredictable ferry again.

Responding to “numerous petitions. . . from the inhabitants of the western counties of this state, praying for the grant of a lottery to raise funds to erect a bridge across said lake, . . . between the villages of East and West Cayuga,” the Legislature authorized a replacement bridge in April 1812, but the construction only began in the winter of 1813.

At that time, according to the 1876 History of Seneca Co., New York:

“Piles were driven from the east shore one-third of the way across, the pile-driver being worked on the ice. When the ice went out a scow was constructed and anchored at the work; on this scow the horse went round and round upon his weary circle, winding up the rope which drew up the hammer.

“The work was vigorously pressed; hands received a dollar and a half per day and paid the same sum for a week’s board. Fever and ague being prevalent, a ration of half a pint of whisky daily was furnished to each man by the company.”

This replacement was called the “new” Cayuga Lake Long Bridge, which operated for some twenty years. It was depicted in a widely circulated woodcut image.

This replacement was called the “new” Cayuga Lake Long Bridge, which operated for some twenty years. It was depicted in a widely circulated woodcut image.

Though fiscally sound and paying a dividend to stockholders, the new bridge had to contend with competition beginning in January 1819 from a new and improved ferry propelled by horses that took twenty to forty minutes to traverse about three miles.

This horse ferry with a length of 50 feet and width of 40 was widely reported, including lengthy newspaper advertisements even in New York City with the headline HORSE BOAT, promising eight wagons and twenty horses could be accommodated as a single load at impressive speeds.

This horse ferry with a length of 50 feet and width of 40 was widely reported, including lengthy newspaper advertisements even in New York City with the headline HORSE BOAT, promising eight wagons and twenty horses could be accommodated as a single load at impressive speeds.

In March 1825, the Legislature authorized a new bridge — known as the Free Bridge since there was no toll — that was started in 1826 across the Seneca River well beyond the limits that protected the Cayuga Lake Long Bridge about six miles to its south.

It was not completed until July 4, 1830 because of prolonged litigation with the Cayuga Bridge Company. Tax

levies were sought to support the maintenance and repair of the Free Bridge.

Besides the Horse Boat, the second “new” Cayuga Bridge had additional major competition with the construction in 1833 of an additional bridge crossing just to the north of earlier ones now in disrepair to meet the demand.

The building of a railroad bridge and the opening of canals, first the completion of the Cayuga-Seneca Canal in 1816 and the Erie Canal in 1825, further diminished the importance of the remaining bridges. Moving heavy goods by water or rail was much cheaper than over land connected by a bridge.

Perhaps at least partially to meet the competition of the Free Bridge route and the canals, a third “new” Cayuga Bridge was built in 1833 by the Cayuga Bridge Company just to the north of the route of the original Cayuga Lake Long Bridge.

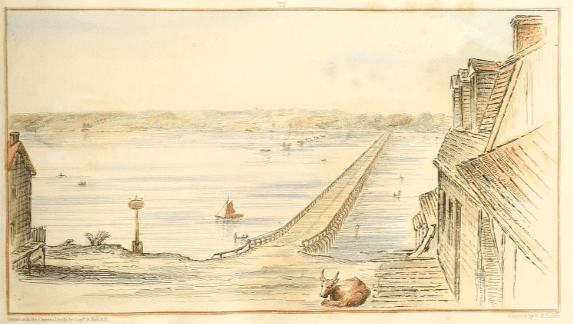

It was this “new” Cayuga Lake Long Bridge that Basil Hall wrote about in his Travels in North America, in the years 1827 and 1828. He called the lake “one of those numerous inland seas with which the northern part of the Great State of New York abounds,” remarking “to my shame, I confess, I never heard its name till a week before I saw it.”

Commenting on the length of the crossing, he stated “It took me fifteen minutes and twenty seconds, smart walking, to go from one end to end, and measured 1850 paces. The toll-keeper at the eastern end informed me, that it was a mile and eight rods in length [5,412 feet]… I amused myself by making a sketch of it with the Camera Lucida [an optical projection device].”

His hand-colored Camera Lucinda image was published separately in 1829 in a rare collection of Hall’s work. Black and white replicas of this hand-colored image are better known.

His hand-colored Camera Lucinda image was published separately in 1829 in a rare collection of Hall’s work. Black and white replicas of this hand-colored image are better known.

In March 1832 there were reports in an Ithaca newspaper that the Cayuga Bridge had been destroyed by ice and carried away. However, this proved to be false since there was damage that was repaired, and the bridge was passable in April.

The saga of the Cayuga bridges, most notably the Cayuga Long Bridge in its various manifestations after 1800, came to an end in 1857 as the Cayuga Bridge Company went broke as a result of diminished revenues. Inadequate maintenance, moreover, and ice buildup in January and February rendered the bridge impassable.

The last toll was taken on February 26, 1857. Still, the next year on April 15, 1858, the State Legislature voted to incorporate a new Cayuga Bridge Company that proposed erecting a new bridge — “a good and substantial one … not less than ten feet in width with four or more turnouts.”

This projected bridge was never constructed. Today, aerial photographs reveal some of the ghosted pilings as black dots of one of the nineteenth century trans-lake bridges beneath the surface of Lake Cayuga’s waters to the west of the Village of Cayuga.

This projected bridge was never constructed. Today, aerial photographs reveal some of the ghosted pilings as black dots of one of the nineteenth century trans-lake bridges beneath the surface of Lake Cayuga’s waters to the west of the Village of Cayuga.

Ronald G. Knapp and Terry E. Miller are the authors of Theodore Burr and the Bridging of Early America: The Man, Fellow Bridge Builders, and Their Forgotten Timber Spans (2023).

This essay is sponsored by the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges. It’s part of a series of essays about covered bridges in New York State – you can read them all here.

Illustrations and Sources: Basil Hall, Forty Etchings Made from Sketches Made with the Camera Lucinda, 1829; Early trestle design from Trestles 101; Finger Lakes Map By Michael J, CC BY-SA 3.0; Great Genesee Road map, showing the Military Tract, Iroquuois Trail, and Erie Canal transportation routes (Great Genessee Road); Tolls in The Minerva, & Mercantile Evening Advertiser, August 15, 1797; John Warner Barber and Henry Howe woodcut showing Cyuga Long Bridge, 1841 (Historical Collections of the State of New York); Horse Boat Ferry advertisement in the The New-York Evening Post, March 10, 1819; Basil Hall, Forty Etchings Made from Sketches Made with the Camera Lucinda, 1829; and a satellite image showing the long bridge’s ghost underwater pilings.

Recent Comments