The John J. McGraw Monument in Truxton, New York is a nice sculpture, dignified and uncomplicated.

The John J. McGraw Monument in Truxton, New York is a nice sculpture, dignified and uncomplicated.

Yet it captures a great deal of what might be described as the essence of baseball, with the man himself portrayed in bas-relief on a truncated obelisk wearing his New York Giants pinstriped flannels and cap.

The entire monument is surmounted by an oversized, yet perfectly scaled baseball on a stepped plinth The sculpture is engraved on the front with his name and deeds, and mentions he was “One of Baseball’s Immortals.” The ball is inscribed with the interlocking initials NL, for National League, and the rear inscription details how the monument was funded by a special ball game played in town.

Truxton, in northeastern Cortland County, certainly had every right to be proud of John McGraw. He played big league baseball with a skill and passion that was new to the game. He moved into management when his playing days ended and was an incredible judge of baseball talent, and his player development program made the Giants perennial contenders.

He was well rewarded financially, and was made an ownership partner in the franchise. Health issues forced John McGraw into retirement mid-way through the 1932 season, yet he was able to manage the National League team in the first-ever All-Star Game in 1933.

He passed away the subsequent year at age 60. John McGraw was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937, acknowledgement of his tremendously successful career, and perhaps the impetus of creating a memorial in his hometown of Truxton.

John McGraw’s father arrived in Upstate New York as an infant, as his parents emigrated from Ireland in 1844, making him just the right age to be called upon by the United States Army for their during the Civil War. Privations of the times made the future ballplayer’s upbringing and home life difficult.

This was further complicated by his mother’s chronic illness and premature death, and he was taken in by Mr. and Mrs. David Goddard, where he joined the couple’s six sons on their rural farm just outside of the village.

John McGraw displayed a talent for baseball at a very young age. He is mostly remembered as a flashy and fast infielder, but he could reliably be called to the mound to pitch. He once was chided following mass at St. Patrick’s Church for having a baseball in his back pocket protruding obviously beneath his cassock.

John McGraw left Truxton as a teenager, and attended the school of hard knocks before continuing his education at St. Bonaventure University. He played professional ball at Olean and other minor league teams before breaking into the big leagues with Baltimore.

After moving to New York and the National League, John McGraw took an active interest in the theater and performers, and also horse racing; at one time he was an ownership partner in Oriental Park race track at Havana, Cuba.

His Giants teams were performers and the path to the pennant regularly passed through the Polo Grounds, their home field along the Harlem River in the upper reaches of Manhattan, beneath Coogan’s Bluff. Even with all his success in Gotham, it seems that John McGraw’s hometown was never far off in his mind; throughout his life all his pet Airedale and Boston bulldogs were named Truxton.

Many years later the Homer Post retold that he “promoted an ideal field in that village on the same old sand lot where he first wound his fingers around a horsehide cover. Many a Truxton boy has slid-for-home wearing a pair of pants not long before discarded by some big-leaguer on the Giants. Yes, Old John sent up a lot of good equipment to Truxton — and the boys up there have played like fools to live up to the honor!”

Many residents of Truxton remembered John McGraw and how, despite a very humble upbringing, he went on to great success and fame. In the late 1920s residents joined together to purchase a piece of ground where baseball could be played. This site was near the village, and fairly level being along the Tioughnioga River, but had mostly been used in the past as a dumping ground.

Many residents of Truxton remembered John McGraw and how, despite a very humble upbringing, he went on to great success and fame. In the late 1920s residents joined together to purchase a piece of ground where baseball could be played. This site was near the village, and fairly level being along the Tioughnioga River, but had mostly been used in the past as a dumping ground.

Local farmers contributed their time, teams and tractors toward leveling and seeding the field. The group received encouragement, morally and financially from the manager of the New York Giants, and incorporated in June of 1928 as the Truxton Athletic Association, which would allow this group and their property to perpetuate through corporate law.

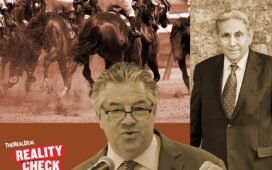

In 1938 a special committee was formed to create some type of permanent memorial to John McGraw, and a Syracuse attorney named Willfred E. Hoffman was made chairman. The best fund-raising plan the memorial committee could think of was to bring the New York Giants to Truxton, and to feature them in a ballgame.

Certainly, a game with the Big League team in Cortland County would be a rapid way to assemble funds, even though their venue would be far from major league.

From the perspective of the present day, it seems amazing the Giants agreed to play a mid-season exhibition game, but they did indeed. This is a real testament to how strongly the Giants ownership felt about the man who managed the ball club for more than thirty years. The Giants wanted to properly memorialize John McGraw’s life and accomplishments, and Truxton was the right place.

As the calendar changed to June and the weather warmed, the Giants were in second place behind the league leading Pittsburg Pirates. The Giants owner, Horace Stoneham, committed his ball club to a memorial fund raising game in Truxton in early August.

Frank Graham, normally a turf writer whose New York Sun column was titled “Setting the Pace,” wrote in the June 13, 1938 edition, “Long ago and far away… and a strange thing to be thinking of, maybe, with… all the other exciting things going on in sport. It looks as though a man should have his mind on the things about him today and not be reaching back through the years like that. But blame it on that news item from Truxton and on the name of John McGraw, the very mention of which, even now, stirs a thousand memories.”

John McGraw must have been a difficult man to honor, in that to achieve his many successes he had to be bold and forthright. I do not think he shied from anything and was as bold as brass. John McGraw’s skills would have been honed in a different era, before baseball was sanitized and made family-friendly.

A man of his era, someone who really figured out the system as it developed, and how to be successful inside that same system while being based in New York City, would have been understandably headstrong. He was so impetuous and obstinate that he actually refused to let the New York Giants participate in the 1904 World Series, and no series took place that season.

He looked down his nose at the rival American League, once notoriously decrying their franchise in the City of Brotherly Love as what he termed a “white elephant” (following this quote the Philadelphia A’s manager, the legendary Connie Mack, adopted an elephant logo which adorns the uniform of the Oakland A’s to this day, with this mascot known as Stomper).

John McGraw ran his teams as a despot, and was derisively known as “Little Napoleon” by both fans and players. John McGraw once described his managerial style by saying, “with my team I am an absolute czar. My men know it. I order plays and they obey. If they don’t, I fine them.”

Because he had a deaf pitcher on his staff, he began having his players use American Sign Language on the field, and could signal plays and instructions from the dugout. A zealous competitor, some of his novel strategies were at the least impolite, and pushed the limits of the baseball rule book, leading others who considered his type of play just beyond clever, to refer to him as “Mugsy.”

This particular sobriquet also was a reference to his pugilistic tendencies on the ball field. John McGraw had a contentious nature, leading to his 131 ejections from ball games, a major league record for decades which was only recently broken. John McGraw commented on this stating, “Sportsmanship and easygoing methods are all right, but it is the prospect of a hot fight that brings out the crowds.”

This particular sobriquet also was a reference to his pugilistic tendencies on the ball field. John McGraw had a contentious nature, leading to his 131 ejections from ball games, a major league record for decades which was only recently broken. John McGraw commented on this stating, “Sportsmanship and easygoing methods are all right, but it is the prospect of a hot fight that brings out the crowds.”

It is widely accepted that major league baseball needed to adopt the four-umpire system due to the many underhanded tactics employed by the McGraw managed teams, such as grabbing or tripping opposing base runners or hiding additional baseballs on the field. John McGraw was single-minded in describing his methods, stating, “the main idea is to win.” His success at the Polo Grounds went on for years, and added up to decades.

The memorial game in Truxton was scheduled for Monday August 8, 1938. The Giants would travel there, following a weekend series with the league leading Pirates in New York, as the first stop on a road trip to Boston. The New York Giants in the memorial game would play a local ‘all-star’ team, which would be referred to as the Truxton Giants.

The traveling secretary packed the Giants home uniforms for use by the Truxton team, and the big leaguers would wear their road “grays.” The game would be played at a ball diamond in the village, which John McGraw had a financial hand in acquiring, and known to this day as McGraw Field.

The ball field features a charming covered wood grandstand, fitted with flagpoles at each end of the gable roof, in place behind home plate. Yet for the large crowd anticipated, bleachers were added at the venue. Both Cornell and Syracuse Universities, who also supplied players to the Truxton Giants, graciously loaned these bleachers.

This temporary seating was placed from the grandstand to each foul pole, limiting foul territory, but creating a great vantage point for fans. Bleachers were also placed beyond the rope outfield fence, completely encircling the playing field with spectator space, which also created an admission barrier.

Big league baseball was in full swing on that first weekend of August 1938, with the media and fans all abuzz about Walter O. Briggs, owner of the Detroit Tigers, firing his manager, the stalwart Mickey Cochrane. Babe Ruth was a coach with the Dodgers, with many fans expecting him to shortly replace the venerable Burleigh Grimes as manager, but you never could tell what might happen in Brooklyn.

The Reds were in for a weekend series at Ebbets Field and Roscoe McGowen would report the games in the New York Times. The Times would send him next on assignment to Truxton. The summer weather was oppressive in New York, with the previous 14 days being very dry with above normal temperatures.

On Saturday August 6, the heat broke and showers began along the Great Lakes and across the Empire State. A ferocious thunderstorm at Jacob Riis Park on Long Island’s southern shore killed three swimmers and injured another 15. The Yankee game at Cleveland was delayed almost an hour, and the Reds at Dodgers was postponed, as were the Pirates vs. Giants at the Polo Grounds.

Both of New York’s National League teams scheduled double headers for Sunday with the Dodgers earning a sweep. The first-place Pirates dealt a blow to the Giants’ pennant hopes, and heartbreak to the 50,468 in attendance, by winning two games from the home team, despite Mel Ott homering in his first plate appearance in both games.

Monday in New York saw more large thunderstorms with heavy downpours, which caused the traffic signal control system in Manhattan to fail, leaving some motorists stalled in Times Square for hours. The weather in Truxton, in contrast, was absolutely perfect for baseball, a wonderful summer day, with the corn coming into its own.

The Giants, like all big league teams of that era, had their own rail cars. They entered the Lehigh Valley Railroad system, and traveled as far as Ithaca, where the players were treated to breakfast at the Hotel Ithaca. The Giants’ rail cars would be left there for a later train, which would rendezvous with the team in Truxton. School buses were used to transfer the Giants from Ithaca to Truxton along State Route 13.

When the team arrived, the village was crowded with people, and a delightful fair-like atmosphere pervaded the environs. A resourceful pilot set up an airfield in a Hartnett family pasture, and was hawking rides aloft to see the exciting happenings.

The memorial committee had a souvenir scorecard printed with team rosters and a brief biography of John McGraw, and they were widely distributed. Every church group in town had a concession stand of some type, peddling hot dogs, soda pop and lemonade. Enterprising neighbors were renting their front lawns for parking.

The Syracuse Post-Standard quoted 50-year resident and village cemetery superintendent B.A. Freeman stating “this is the greatest day this town has ever seen.”

Lieutenant Governor M. William Bray was on hand at the invitation of Hoffman’s committee. The New York Giants brought their whole baseball family, with team secretary Ed Brannick, who had started his professional career as a Polo Grounds vendor, or as they were called in those days, a “butch.”

Team owner Horace Stoneham made the trip as did Polo Grounds grounds-keeper Henry Fabian who had played minor league ball with the honored guest. Future Baseball Hall of Fame members Travis Jackson and Mel Ott signed autographs for jovial fans.

As game time neared everyone began making their way into McGraw Field, and the air was filled with the sound of the crowd. Mrs. John McGraw was visiting her friends, Mr. & Mrs. C. Leonard O’Connor of Cortland and staying with them at their home at 37 Tompkins Street, which we know today as the 1890 House Museum; also a guest of Judge and Mrs. O’Connor was Horace Stoneham.

His Honor was a boyhood friend and teammate of “Jawn” McGraw in Truxton and his baseball path took him to the state Supreme Court bench, via the Syracuse University Varsity nine, and he frequently used the manager’s box at the Polo Grounds.

Certainly the guest of honor for the occasion in Truxton was John McGraw’s wife Blanche Sindall McGraw and she had granted an interview to the Syracuse American in the O’Connor home the evening before the memorial game. The August 7 evening edition mentioned “She seems to live in the memory of the fightin’ Irish boy from Truxton, who made baseball history with flaming colorful deeds on the diamond.”

Certainly the guest of honor for the occasion in Truxton was John McGraw’s wife Blanche Sindall McGraw and she had granted an interview to the Syracuse American in the O’Connor home the evening before the memorial game. The August 7 evening edition mentioned “She seems to live in the memory of the fightin’ Irish boy from Truxton, who made baseball history with flaming colorful deeds on the diamond.”

She said while in a scrap his favorite rumbling expression was “Truxton Against The World!” Nearly two decades after her husband’s death, she published a biography titled The Real McGraw, where she detailed her husband’s talent-seeking ability, crossing the color barrier decades before it actually happened when she wrote, “Without mincing words, John bemoaned the failure of baseball, himself included, to cast aside custom or unwritten law, or whatever it was, and sign a player on ability alone, regardless of race or color.”

Blanche McGraw received a loud ovation from the crowd and she was seated directly behind home plate. Joining her in this place of honor were two of John McGraw’s sisters, Mrs. James Donnelly of Camillus, and Mrs. Frank Gray of New Canaan, Connecticut. Jack McGraw, a second cousin, was on the Truxton Giants roster.

St. Mary’s School Band from Cortland played the National Anthem, as the crowd sang along. Bob Kenefick, a sportscaster on station WFBL, Syracuse, and a daily sportswriter in that community was the master of ceremonies. Following the anthem, he asked the audience to remain standing for a moment in silence, to contemplate the memory of John McGraw. He then read a poem titled “John J. McGraw Comes Home,” penned by fellow sportswriter Joseph H. Adams of the Syracuse Post-Standard, which reverberated through the entire village.

George Wiltse of Syracuse, who had a successful career as a left-handed pitcher for John McGraw’s Giants, made a short tribute. Wiltse, whose long arms against his gangling frame earned him the nickname “Hooks,” then moved onto the field where he umpired the bases. The home plate umpire, also from Syracuse, was former big league pitcher-turned-umpire Bill Dineen.

An interesting side note is that in a game in Baltimore on April 29, 1902 while on the mound Bill Dineen hit John McGraw with a pitched ball five times during one at bat, yet he was never awarded first base as the umpire did not believe he made any effort to avoid being struck.

John McGraw sat down in the batter’s box and refused to leave the field. This protest developed into suspensions and fines, which led John McGraw to move to the New York Giants and the National League.

With the official ceremonies concluded, everyone’s attention turned to the fun of baseball. It was “play ball” with the visiting New York Giants batting first against Bob Nugent, pitching for the Truxton Giants. He held the big leaguers scoreless into the third, when shortstop Dick Bartell stole home for the first run of the game.

The Giants had just recently purchased the contract of pitcher Johnny Wittig, and manager Bill Terry wanted to see him pitch before the team got to Boston to face Casey Stengel’s Bees (Braves). Bill Terry had been manager of the Giants since John McGraw’s illness prevented him from continuing after June 1932.

Memphis Bill as he was known (still the last National League player to bat above .400 for a seasonal average), continued to play first base and manage until 1936 when his playing days ended, and he managed full time.

However, for the game in Truxton, he put himself back into the lineup and returned to first base. Wittig did not disappoint his manager, pitching six scoreless innings against Truxton, while surrendering only two hits, and helping his own cause by slapping a double while at bat.

Between innings, the crowd was entertained by popular tunes played by the Cortland American Legion Fife and Drum Corps, the Ten-Town Band of Tully and the St. Mary’s School band. The spectators sang along as they fanned away the August heat with their souvenir scorecards.

Those who could not afford the $1.10 admission price, including many children, were able to follow the progress of the game with announcements of the portable loudspeakers, as they looked on from the margins.

The big league Giants broke loose in the top of the fifth inning, hitting three doubles. These hits, combined with an outfield error, allowed the New York nine to post three more runs on the scoreboard. They added another two runs in the top of the seventh, to take a 6-0 lead.

In the bottom of the seventh, the Giants manager Bill Terry brought himself into pitch. This move, mostly to spare his pitching staff for their pennant race with the Pirates, delighted the crowd.

The cozy confines created by the placement of the bleachers at McGraw Field accounted for the large number of souvenir baseballs taken home by the locals. An aggregate of 88 balls were used during the game. This total was padded by the major league Jints bouncing three ground-rule doubles into the crowd.

The visiting Giants added two more runs in the top of the ninth inning, bringing their total to eight runs. The Truxton Giants came alive during their last ups in the bottom of the ninth, with back-to-back singles.

Their hitting star Nick Cappaletti, a seventeen-year-old lad on loan from the Syracuse Chiefs, belted another single off Bill Terry, and drove in the Truxton team’s only run. Final score: New York Giants 8, Truxton Giants 1.

The sun was working its way west along the Tioughnioga River, and shadows began to lengthen as the ballgame concluded. The bovine residents of Cortland County began making their way towards the milking parlors and Roscoe McGowen filed his article to the New York Times sports page through the local Lehigh Valley Railroad telegrapher.

The many spectators started for home and the Giants rail cars awaited their boarding at the Truxton station, which was just beyond right field. The players moved first to the showers at the new Truxton Central School, and then gathered in the dining hall there to enjoy local entertainment.

The next day’s Syracuse Journal reported “The committee in charge of the doings at Truxton did an excellent job of it all the way around. Horace Stoneham, the owner of the Giants, who sat in the back row of the grandstand which seated about 150 persons, was impressed with the ceremonies and was glad that he could do his part by bringing the Giants to town. Mrs. John McGraw, widow of the late leader, had tears in her eyes a number of times.”

The Giants, back in their rail cars and on their way to Boston, were engaged in serious card games and hardly noticed the crowds that had gathered on rail platforms in Cuyler, De Ruyter and Cazenovia and other communities along their route. Memorial committee chairman Wilfred Hoffman reported that 7,650 patrons had attended the game.

The funds collected at the memorial game were converted into the John McGraw Monument we see today in Truxton. The September 29, 1942 Cortland Standard mentions that the sculpture was designed by George Bull of the Nelson Memorial Company of Homer.

The funds collected at the memorial game were converted into the John McGraw Monument we see today in Truxton. The September 29, 1942 Cortland Standard mentions that the sculpture was designed by George Bull of the Nelson Memorial Company of Homer.

Contractor Charles Brosius of Cortland prepared the foundation and built the circular stone retaining wall and the Barre, Vermont firm of Beck and Beck carved the monument of green mountain granite, and made the final installation in Truxton.

The inscription on the front of the monument reads:

“In memory of

John J. McGraw

Born in Truxton

April 7, 1873

Died Feb. 25, 1934

A Great American

One of Baseball’s Immortals

Dynamic Leader of

The New York Giants

For Thirty years”

The rear of the monument is inscribed:

“On August 8, 1938 the New York Giants played an exhibition game with the Truxton ball team in this village which made possible the erection of this memorial.”

John J. McGraw Field is just a short distance from his impressive monument along New York Route 13. The ball field ownership was transferred by the Truxton Athletic Association, Inc. to the Town of Truxton in 1970. The former rail station alongside what is now a town park has been preserved and serves as town offices.

John J. McGraw Field is just a short distance from his impressive monument along New York Route 13. The ball field ownership was transferred by the Truxton Athletic Association, Inc. to the Town of Truxton in 1970. The former rail station alongside what is now a town park has been preserved and serves as town offices.

Historical Sign Unveiling

Thanks to the work and dedication of a local resident, a new historical marker will be installed in Truxton on August 2, 2025. William Swisher, a resident of the area since 1966, and his wife Sarah

have funded and designed a historical marker to memorialize the John J. McGraw baseball field and grandstand in Truxton.

An event has been planned to commemorate the game, which will include the unveiling of the historical marker, replication of activities from the 1938 game and speeches by local representatives. A local exhibition baseball game will be played following the formal event. Production and music for the event will be provided by Songs of the Game.

The historic sign will be revealed on August 2, 2025, begining at 1 pm at the baseball field, 6290 Railroad Street, in Truxton.

Read more New York State baseball history.

Illustrations, from above: The McGraw Monument in Truxton; The original John McGraw Field grandstand (courtesy Society for American Baseball Research); Giants manager John J. McGraw (home whites) welcoming the Highlanders manager Harry Wolverton (road grays ) to the Polo Grounds before the Titanic Game on April 21, 1912 (Library of Congress); John McGraw Field grandstand from the front; The McGraw Monument in Truxton bas-relief of McGraw on the monument; a map showing John McGraw Field and the McGraw monument (Society for American Baseball Research).

Recent Comments